wretched people here to use argol or dried yak-dung

as their only fuel, is another contributory cause. The

heavy, greasy blue fumes of these fires coat the interior

of the squat houses with a layer of soot which it would

be useless .labour to remove. Unfrozen water is almost

non-existent, except during the summer, and, so far at

least as the women are concerned, the dirt which seams

their faces is not perhaps unwelcome, for, as we have

seen, custom compels the disfigurement with kutch (or

raddle resembling dried blood) of the brows and

cheeks of women in Tibet.

Having thus pleaded the cause, I have now to

explain the results of this want of cleanliness upon

the town of Phari. The collection of sod-built hovels,

one or, at most, two storeys in height, cowers under

the southern wall of the Jong for protection against the

wind from the bitterest quarter. The houses prop each

other up. Rotten and misplaced beams project at

intervals through the black layers of peat, and a few

small windows lined with crazy black match-boarding

sometimes distinguish an upper from a lower floor.

The door stands open; it is but three black planks,

a couple of traverses, and a padlock. Inside, the black

glue of argol smoke coats everything. A brass cooking-

pot or an iron hammer, cleaned of necessity by use,

catches the eyes as the only thing in the room of which

one sees the real colour. A blue haze fills the room

with acrid and penetrating virulence. In the room

beyond, the meal is being cooked, and a dark object

stands aside as one enters. It is a woman, barely

visible in the dark. Everything in the place is coated

and grimed with filth. At last one distinguishes in a

rude cradle and a blanket, both as black as everything

else, an ivory-faced baby. How the children survive

is a mystery. It is the same in every house. Nothing

has been cleaned since it was made, and the square hole

in the flat roof, which serves at once to admit light and

air, and to emit smoke, looks down upon practically the

same interior in five hundred hovels.

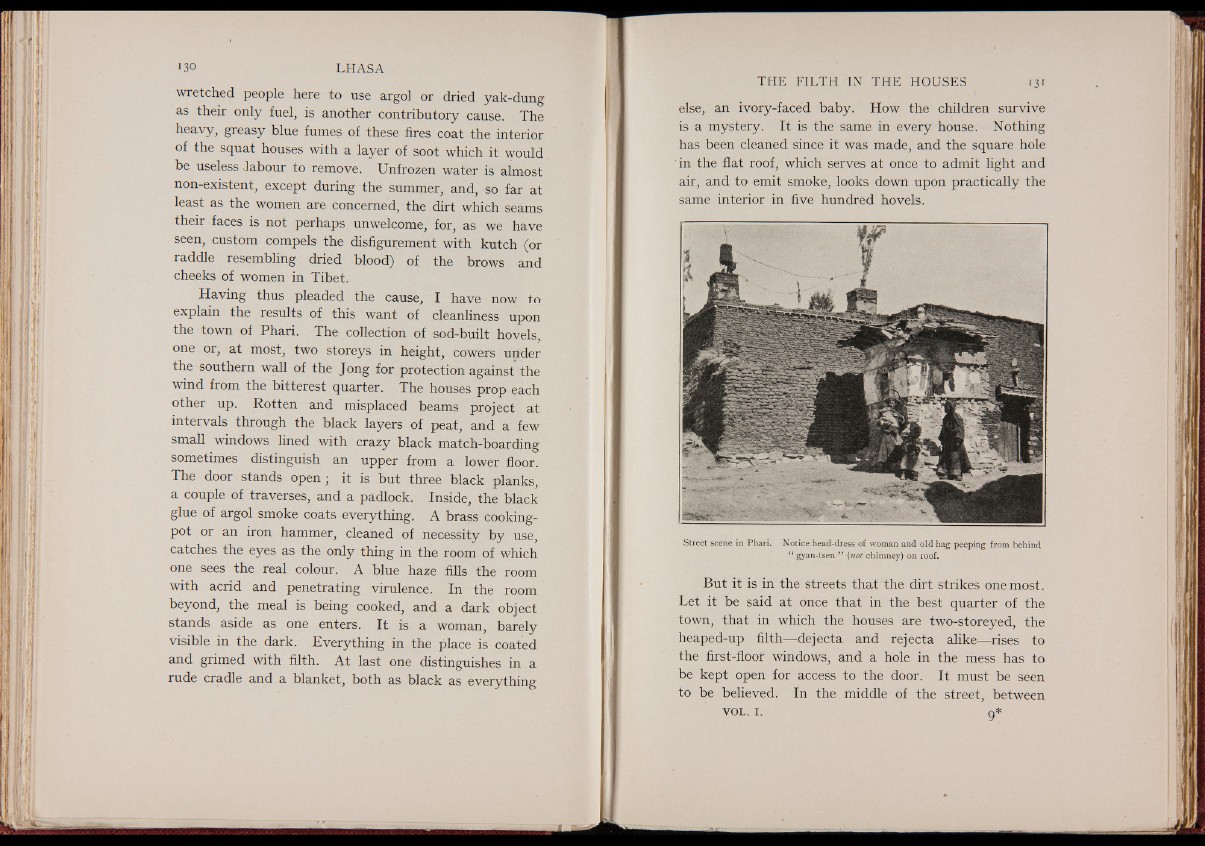

Street scene in Phari. Notice head-dress of woman and old hag peeping from behind

“ gyan-tsen ” {not chimney) on roof.

But it is in the streets that the dirt strikes one most.

Let it be said at once that in the best quarter of the

town, that in which the houses are two-storeyed, the

heaped-up filth— dejecta and rejecta alike— rises to

the first-floor windows, and a hole in the mess has to

be kept open for access to the door. It must be seen

to be believed. In the middle of the street, between

v o l . H 0 *