the country, and do not scruple to make the fullest

use of the privileges which their position gives them.

The right of demanding transport, both by man and

beast, is rigorously exacted, and it is one of the

absurdities of the whole situation, that a race nominally

and locally dominant, but politically without power or

influence of any kind, should still look down with undisguised

contempt upon the people whom they have

shown themselves wholly unable to manage. The

children of these temporary marriages vary their nationality

with their sex. The girls are Tibetans, the boys

are Chinamen— with a difference ; for special names are

in use to indicate these hybrids.

As one rides through, the old familiar smell of China

usurps the musk and grease and incense of Tibet. The

villages are perhaps more cleanly than those of the

people of the country, and this, to those who know

how filthy Chinese villages can be, will suggest some

notion of the amazing dirt of everything Tibetan.

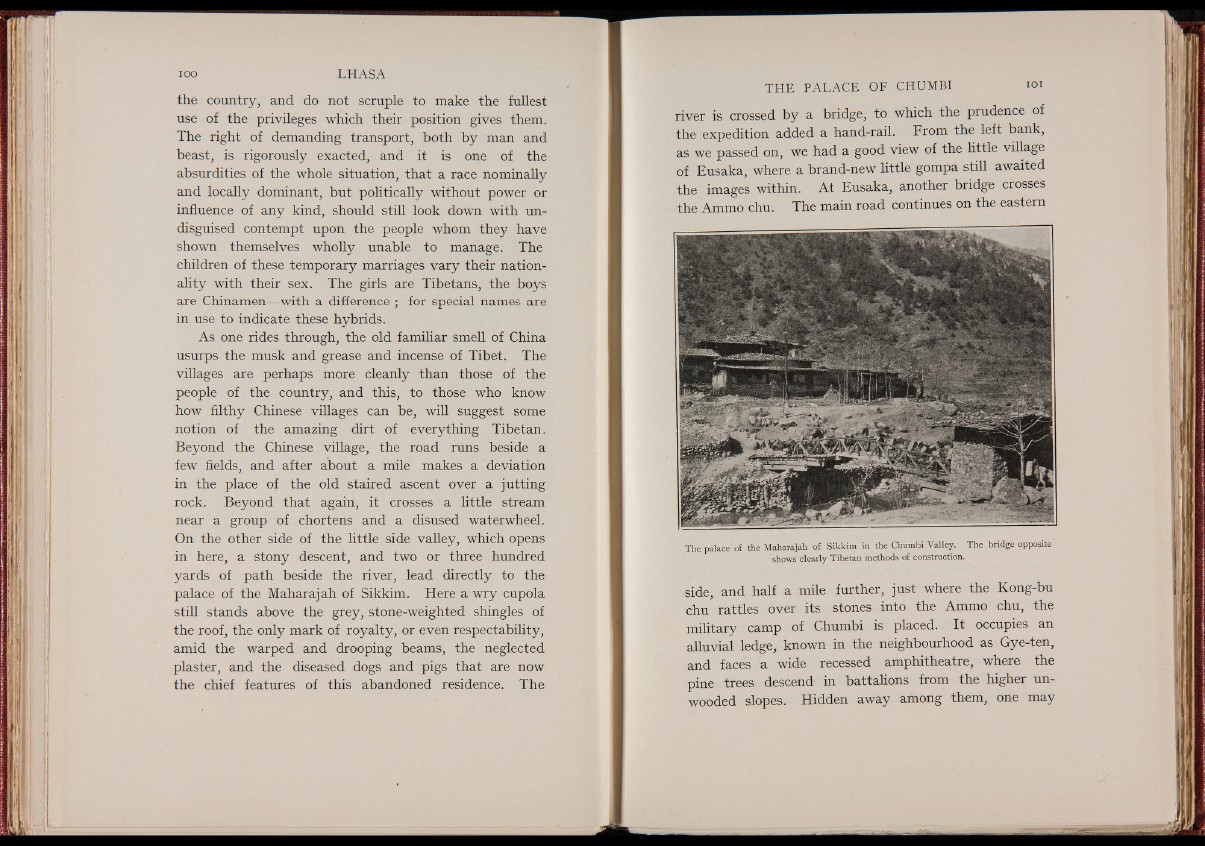

Beyond the Chinese village, the road runs beside a

few fields, and after about a mile makes a deviation

in the place of the old staired ascent over a jutting

rock. Beyond that again, it crosses a little stream

near a group of chortens and a disused waterwheel.

On the other side of the little side valley, which opens

in here, a stony descent, and two or three hundred

yards of path beside the river, lead directly to the

palace of the Maharajah of Sikkim. Here a wry cupola

still stands above the grey, stone-weighted shingles of

the roof, the only mark of royalty, or even respectability,

amid the warped and drooping beams, the neglected

plaster, and the diseased dogs and pigs that are now

the chief features of this abandoned residence. The

river is crossed by a bridge, to which the prudence of

the expedition added a hand-rail. From the left bank,

as we passed on, we had a good view of the little village

of Eusaka, where a brand-new little gompa still awaited

the images within. At Eusaka, another bridge crosses

the Ammo chu. The main road continues on the eastern

The palace of the Maharajah of Sikkim in the Chumbi Valley. The bridge opposite

shows clearly Tibetan methods of construction.

side, and half a mile further, just where the Kong-bu

chu rattles over its stones into the Ammo chu, the

military camp of Chumbi is placed. It occupies an

alluvial ledge, known in the neighbourhood as Gye-ten,

and faces a wide recessed amphitheatre, where the

pine trees descend in battalions from the higher unwooded

slopes. Hidden away among them, one may