But this was essentially and, what is more to the

point, apparently also a different thing from the

passage of troops.

The road to the J elep was therefore at first adopted

for more reasons than the mere fact that so much at

least of the long journey was familiar from our experience

in 1888. In the last chapter I have given

some description of the road between Rang-po and

Chumbi. From this point onwards the interest was

doubled for those who penetrated for the first time

through its gorges. From the Maharajah’s palace there

is a view of the windings of the valley to the point

where the flat alluvial spur of New Chumbi juts out from

the e a s t; the river here makes a final turn and the

high wooded shoulder of the hill above cuts off all view

of the features of the upper reaches of the river. In

this part of the valley there was not perhaps very much

to attract the eye. Certainly in winter, when the first

sight of it was obtained, there was nothing to suggest

the extraordinary beauty of the brief summer months.

The hills come down steeply on either side, elbowing

the quick Ammo chu into a tortuous and almost torrential

course. Rinchengong itself is a straggling hamlet

with a few good houses in it, originally collected there,

not only as a station on the high road to India, but

as a convenient colony for the service - of the monks

of the Kag-ue monastery high on the hill above. The

poorer houses are huddled together, dirty and unkempt,

in the bed of the stream which here flows down from

Ya-tung a mile or two up the valley. The better houses

are removed a few hundred yards away. Some, across

the river, are attached to fertile fields, and two, at least,

on this side have evidently belonged to owners of some

taste and refinement. In the middle of the town, the

large handsome house of Ugyen Kazi stands up brave

with fluttering prayer flags beneath the steep sandy ridge,

crowned with the fir trees which jut out and protect

Rinchengong from the northern blast down the valley.

Up above the houses, just where this promontory

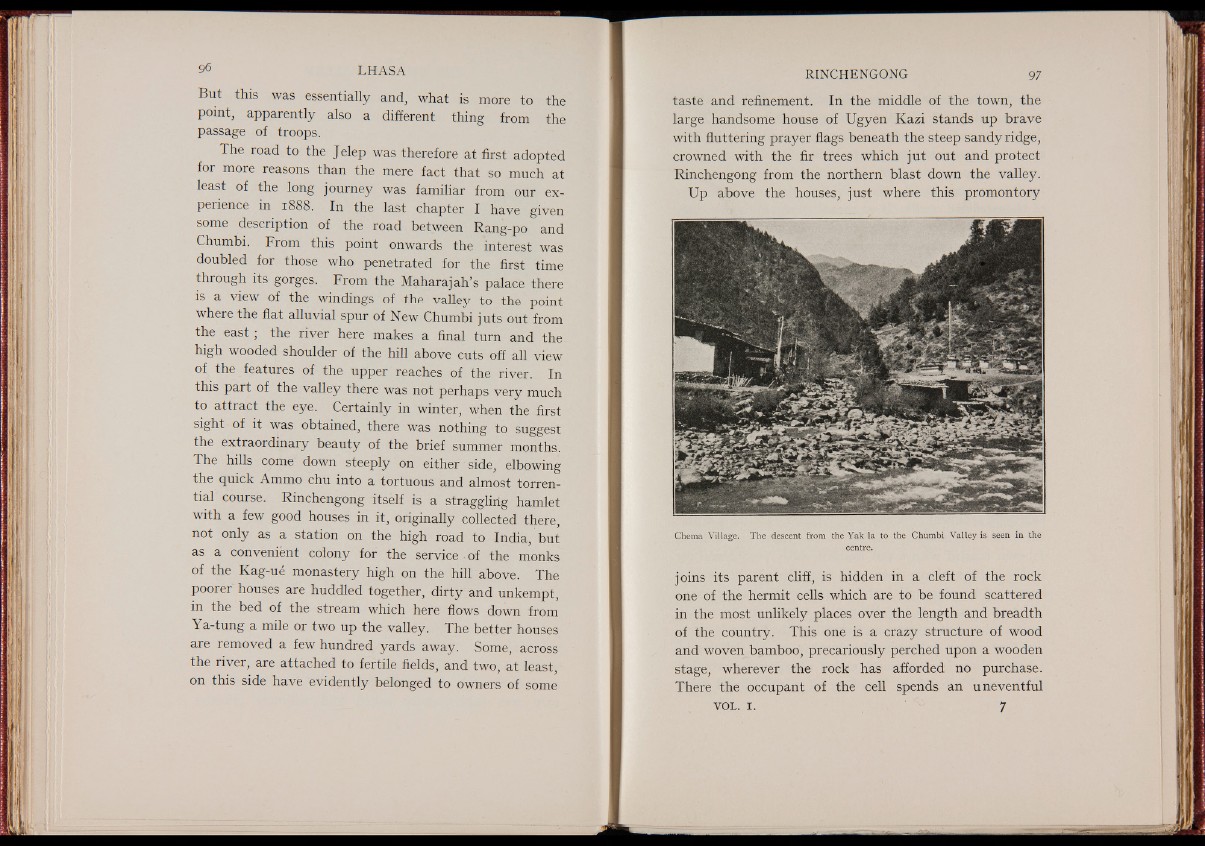

Chema Village. The descent from the Y a k la to the Chumbi Valley is seen in the

centre.

joins its parent cliff, is hidden in a cleft of the rock

one of the hermit cells which are to be found scattered

in the most unlikely places over the length and breadth

of the country. This one is a crazy structure of wood

and woven bamboo, precariously perched upon a wooden

stage, wherever the rock has afforded no purchase.

There the occupant of the cell spends an uneventful

v o l . 1. 7