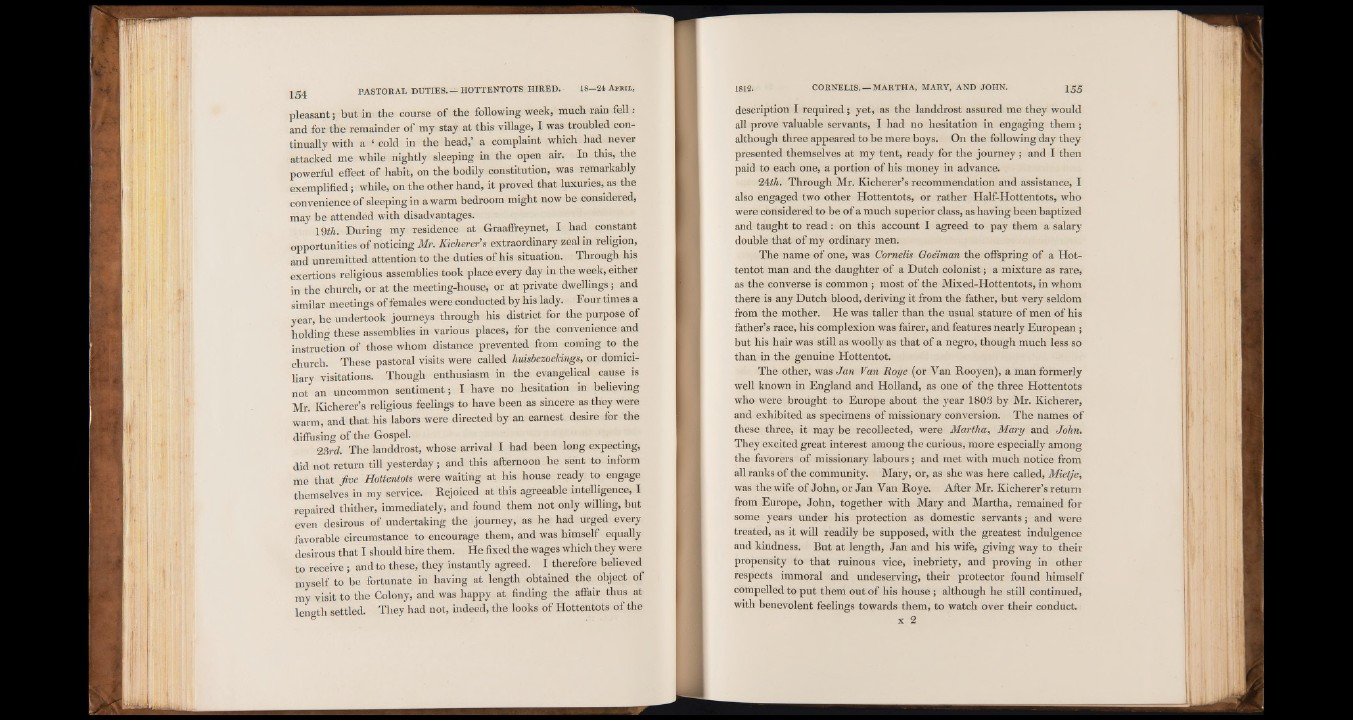

pleasant; but in the course of the following week, much rain fell :

and for the remainder of my stay at this village, I was troubled continually

with a II cold in the head,’ a complaint which had never

attacked me while nightly sleeping in the open air. In this, the

powerful effect of habit, on the bodily constitution, was remarkably

exemplified; while, on the other hand, it proved that luxuries, as the

convenience of sleeping in a warm bedroom might now be considered,

may be attended with disadvantages.

19th. During my residence at Graaffreynet, I had constant

opportunities of noticing Mr. Kicherer's extraordinary zeal in religion,

and unremitted attention to the duties of his situation. Through his

exertions religious assemblies took place every day in the week, either

in the church, or at the meeting-house, or at private dwellings ; and

similar meetings of females were conducted by his lady. Four times a

year, he undertook journeys through his district for the purpose of

holding these assemblies in various places, for the convenience and

instruction of those whom distance prevented from coming to the

church. These pastoral visits were called huisbezoekings, or domiciliary

visitations. Though enthusiasm in the evangelical cause is

not an uncommon sentiment; I have no hesitation in believing

Mr. Kicherer’s religious feelings to have been as sincere as they were

warm, and that his labors were directed by an earnest desire for the

diffusing of the Gospel.

23rd. The landdrost, whose arrival I had been long expecting,

did not return till yesterday; and this afternoon he sent to inform

me that jive Hottentots were waiting at his house ready to engage

themselves in my service. Rejoiced at this agreeable intelligence, I

repaired thither, immediately, and found them not only willing, but

even desirous of undertaking the journey, as he had urged every

favorable circumstance to encourage them, and was himself equally

desirous that I should hire them. He fixed the wages which they were

to receive; and to these, they instantly agreed. I therefore believed

myself to be fortunate in having at length obtained the object of

my visit to the Colony, and was happy at finding the affair thus at

length settled. They had not, indeed, the looks of Hottentots of the

description I required; yet, as the landdrost assured me they would

all prove valuable servants, I had no hesitation in engaging them;

although three appeared to be mere boys. On the following day they

presented themselves at my tent, ready for the journey ; and I then

paid to each one, a portion of his money in advance.

‘¡Ath. Through Mr. Kicherer’s recommendation and assistance, I

also engaged two other Hottentots, or rather Half-Hottentots, who

were considered to be of a much superior class, as having been baptized

and taught to read : on this account I agreed to pay them a salary

double that of my ordinary men.

The name of one, was Comelis Goeiman the offspring of a Hottentot

man and the daughter of a Dutch colonist; a mixture as rare,

as the converse is common ; most of the Mixed-Hottentots, in whom

there is any Dutch blood, deriving it from the father, but very seldom

from the mother. He was taller than the usual stature of men of his

father’s race, his complexion was fairer, and features nearly European ;

but his hair was still as woolly as that of a negro, though much less so

than in the genuine Hottentot.

The other, was Jan Van Roye (or Van Rooyen), a man formerly

well known in England and Holland, as one of the three Hottentots

who were brought to Europe about the year 1803 by Mr. Kicherer,

and exhibited as specimens of missionary conversion. The names of

these three, it may be recollected, were Martha, Mary and John.

They excited great interest among the curious, more especially among

the favorers of missionary labours; and met with much notice from

all ranks of the community. Mary, or, as she was here called, Mietje,

was the wife of John, or Jan Van Roye. After Mr. Kicherer’s return

from Europe, John, together with Mary and Martha, remained for

some years under his protection as domestic servants; and were

treated, as it will readily be supposed, with the greatest indulgence

and kindness. But at length, Jan and his wife, giving way to their

propensity to that ruinous vice, inebriety, and proving in other

respects immoral and undeserving, their protector found himself

compelled to put them out of his house ; although he still continued,

with benevolent feelings towards them, to watch over their conduct.

x 2