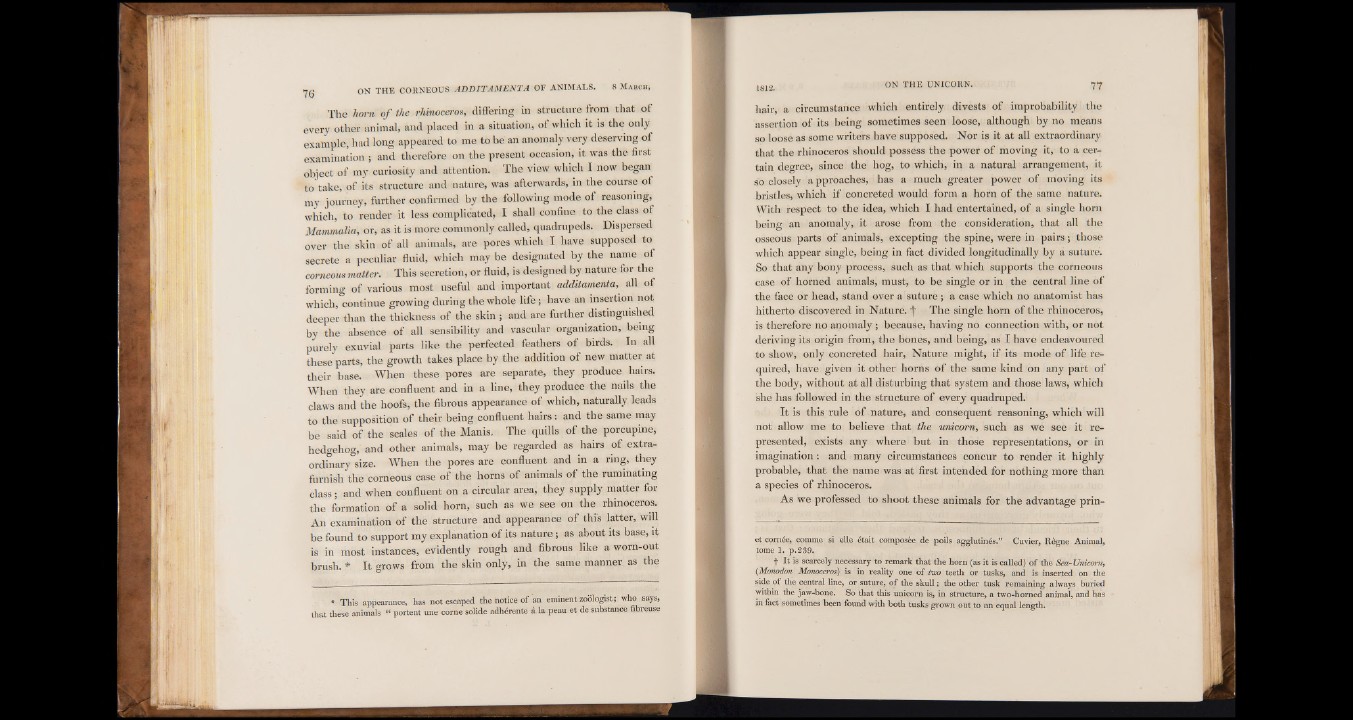

The horn of the rhinoceros, differing in structure from that of

every other animal, and placed in a situation, of which it is the only

example, had long appeared to me to be an anomaly very deserving of

examination ; and therefore on the present occasion, it was the first

object of my curiosity and attention. The view which I now began

to take, of its structure and nature, was afterwards, in the course of

my journey, further confirmed by the following mode of reasoning,

which, to render it less complicated, I shall confine to the class of

Mammalia, or, as it is more commonly called, quadrupeds. Dispersed

over the skin of all animals, are pores which I have supposed to

secrete a peculiar fluid, which may be designated by the name of

corneous matter. This secretion, or fluid, is designed by nature for the

forming of various most useful and important additamenta, all of

which, continue growing during the whole life; have an insertion not

deeper than the thickness of the skin ; and are further distinguished

by the absence of all sensibility and vascular organization, being

purely exuvial parts like the perfected feathers of birds. In all

these parts, the growth takes place by the addition of new matter at

their base. When these pores are separate, they produce hairs.

When they are confluent and in a line, they produce the nails the

claws and the hoofs, the fibrous appearance of which, naturally leads

to the supposition of their being confluent hairs: and the same may

be said of the scales of the Manis. The quills of the porcupine,

hedgehog, and other animals, may be regarded as hairs of extraordinary

size. When the pores are confluent and in a ring, they

furnish the corneous case of the horns of animals of the ruminating

class; and when confluent on a circular area, they supply matter for

the formation of a solid horn, such as we see on the rhinoceros.

An examination of the structure and appearance of this latter, will

be found to support my explanation of its nature; as about its base, it

is in most instances, evidently rough and fibrous like a worn-out

brush. * It grows from the skin only, in the same manner, as the

* This appearance, has not escaped the notice of an eminent zoologist; who says,

that these animals “ portent une corne solide adhérente à la peau et de substance fibreuse

hair, a circumstance which entirely divests of improbability the

assertion of its being sometimes seen loose, although by no means

so loose as some writers have supposed. Nor is it at all extraordinary

that the rhinoceros should possess the power of moving it, to a certain

degree, since the hog, to which, in a natural arrangement, it

so closely a pproaches, has a much greater power of moving its

bristles, which if concreted would form a horn of the same nature.

With respect to the idea, which I had entertained, of a single horn

being an anomaly, it arose from the consideration, that all the

osseous parts of animals, excepting the spine, were in pairs; those

which appear single, being in fact divided longitudinally by a suture.

So that any bony process, such as that which supports the corneous

case of horned animals, must, to be single or in the central line of

the face or head, stand over a suture; a case which no anatomist has

hitherto discovered in Nature, f The single horn of the rhinoceros,

is therefore no anomaly; because, having no connection with, or not

deriving its origin from, the bones, and being, as I have endeavoured

to show, only concreted hair, Nature might, if its mode of life required,

have given it other horns of the same kind on any part of

the body, without at all disturbing that system and those laws, which

she has followed in the structure of every quadruped.

It is this rule of nature, and consequent reasoning, which will

not allow me to believe that the unicorn, such as we see it represented,

exists any where but in those representations, or in

imagination: and many circumstances concur to render it highly

probable, that the name was at first intended for nothing more than

a species of rhinoceros.

As we professed to shoot these animals for the advantage prinet

cornée, comme si elle était composée de poils agglutinés.” Cuvier, Règne Animal,

tome 1. p.239.

f It is scarcely necessary to remark that the horn (as it is called) of the Sea-Unicom,

{Monodon Monoceros) is in reality one of two teeth or tusks, and is inserted on the

side of the central line, or suture,, o f tfie skull ; the other tusk remaining always buried

within the jaw-bone. So that this unicorn is, in structure, a two-horhed animal, and has

in fact sometimes been found with both tusks grown out to an equal length.