people, and the rest were sent to a distant cattle-station for the use

only of his herdsmen.

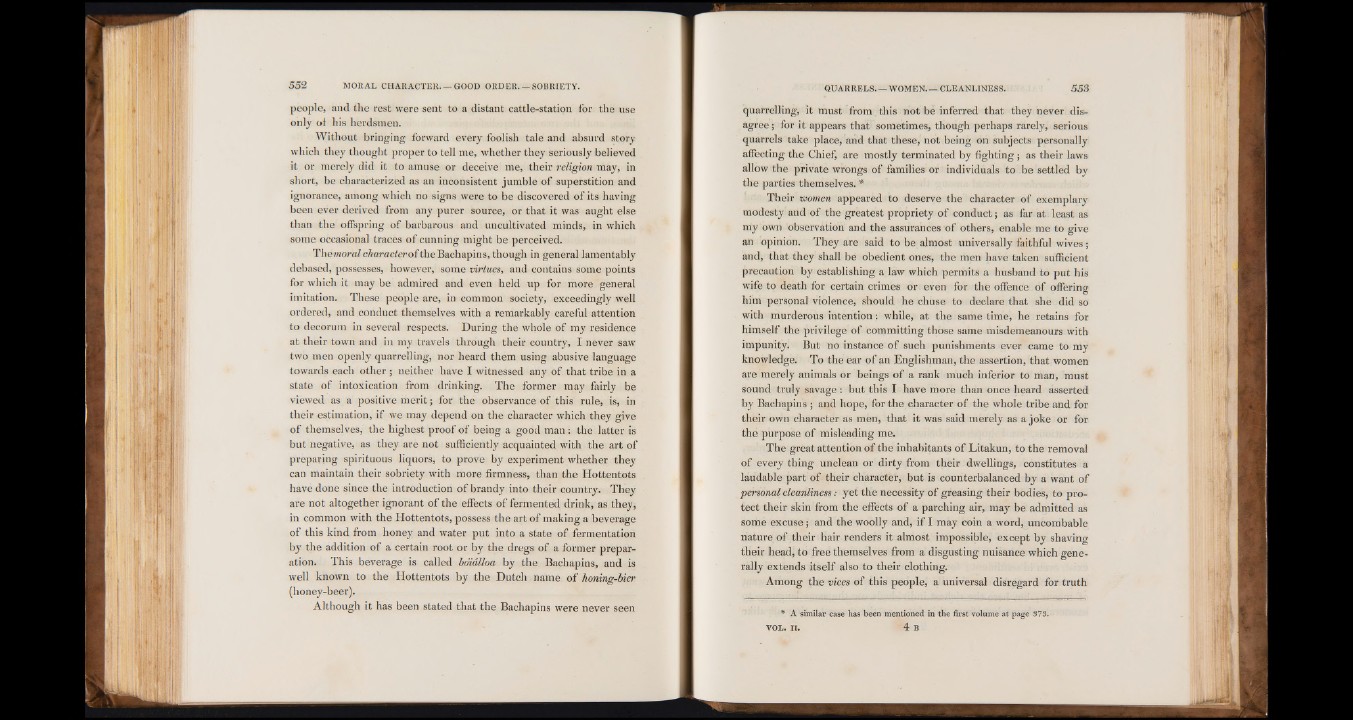

Without bringing forward every foolish tale and absurd story

which they thought proper to tell me, whether they seriously believed

it or merely did it to amuse or deceive me, their religion may, in

short, be characterized as an inconsistent jumble of superstition and

ignorance, among which no signs were to be discovered of its having

been ever derived from any purer source, or that it was aught else

than the offspring of barbarous and uncultivated minds, in which

some occasional traces of cunning might be perceived.

Themoral characteroitheBachapins, though in general lamentably

debased, possesses, however, some virtues, and contains some points

for which it may be admired and even held up for more general

imitation. These people are, in common society, exceedingly well

ordered, and conduct themselves with a remarkably careful attention

to decorum in several respects. During the whole of my residence

at their town and in my travels through their country, I never saw

two men openly quarrelling, nor heard them using abusive language

towards each other; neither have I witnessed any of that tribe in a

state of intoxication from drinking. The former may fairly be

viewed as a positive merit; for the observance of this rule, is, in

their estimation, if we may depend on the character which they give

of themselves, the highest proof of being a good man : the latter is

but negative, as they are not sufficiently acquainted with the art of

preparing spirituous liquors, to prove by experiment whether they

can maintain their sobriety with more firmness, than the Hottentots

have done since the introduction of brandy into their country. They

are not altogether ignorant of the effects of fermented drink, as they,

in common with the Hottentots, possess the art of making a beverage

of this kind from honey and water put into a state of fermentation

by the addition of a certain root or by the dregs of a former preparation.

This beverage is called boialloa by the Bachapins, and is

well known to the Hottentots by the Dutch name of honing-bier

(honey-beer).

Although it has been stated that the Bachapins were never seen

quarrelling, it must from this not be inferred that they never disagree

; for it appears that sometimes, though perhaps rarely, serious

quarrels take place, and that these, not being on subjects personally

affecting the Chief, are mostly terminated by fighting ; as their laws

allow the private wrongs of families or individuals to be settled by

the parties themselves. *

Their women appeared to deserve the character of exemplary

modesty and of the greatest propriety of conduct; as far at least as

my own observation and the assurances of others, enable me to give

an opinion. They are said to be almost universally faithful wives;

and, that they shall be obedient ones, the men have taken sufficient

precaution by establishing a law which permits a husband to put his

wife to death for certain crimes or even for the offence of offering

him personal violence, should he chuse to declare that she did so

with murderous intention: while, at the same time, he retains for

himself the privilege of committing those same misdemeanours with

impunity. But no instance of such punishments ever came to my

knowledge. To the ear of an Englishman, the assertion, that women

are merely animals or beings of a rank much inferior to man, must

sound truly savage : but this I have more than once heard asserted

by Bachapins ; and hope, for the character of the whole tribe and for

their own character as men, that it was said merely as a joke or for

the purpose of misleading me.

The great attention of the inhabitants of Litakun, to the removal

of every thing unclean or dirty from their dwellings, constitutes a

laudable part of their character, but is counterbalanced by a want of

personal cleanliness: yet the necessity of greasing their bodies, to protect

their skin from the effects of a parching air, may be admitted as

some excuse; and the woolly and, if I may coin a word, uncombable

nature of their hair renders it almost impossible, except by shaving

their head, to free themselves from a disgusting nuisance which generally

extends itself also to their clothing.

Among the vices of this people, a universal disregard for truth

* A similar case has been mentioned in the first volume at page 373.

VOL. II. 4 B