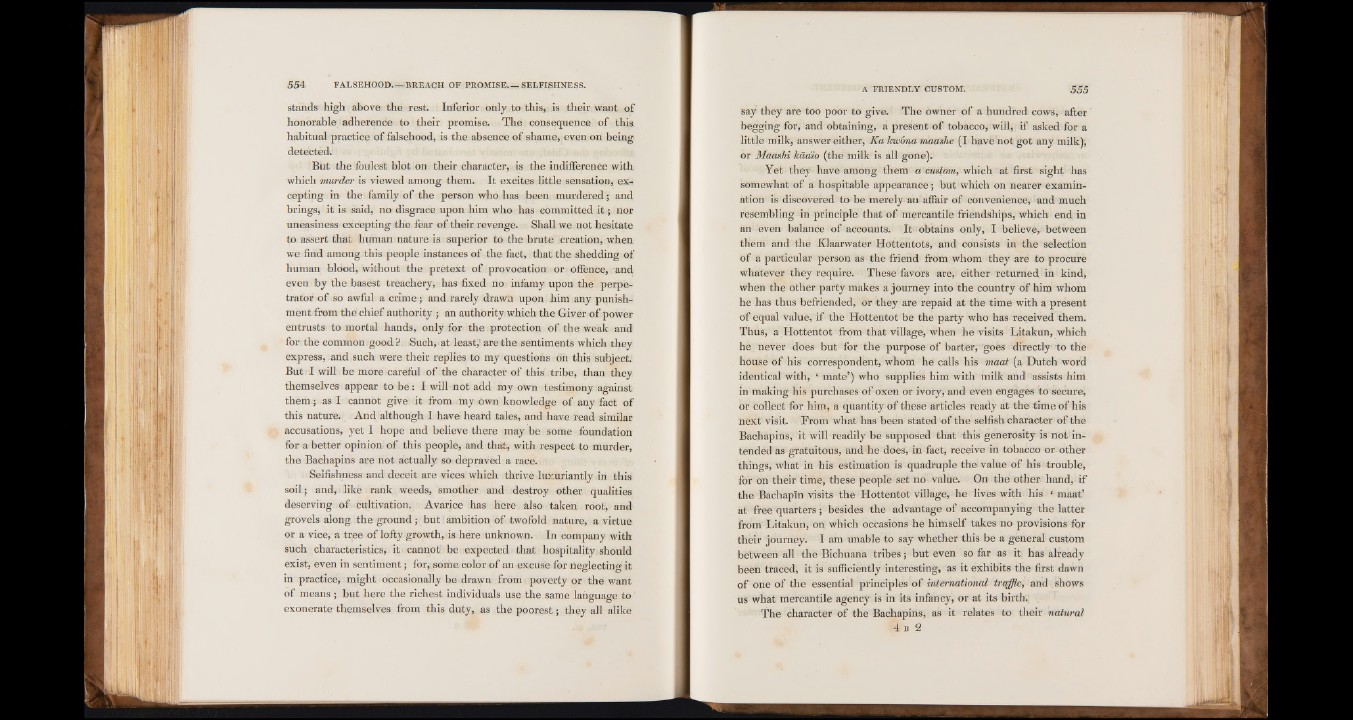

5 54 FALSEHOOD BREACH OF PROMISE SELFISHNESS.

stands high above the rest. Inferior only to this, is their want of

honorable adherence to their promise. The consequence of this

habitual practice of falsehood, is the absence of shame, even on being

detected.

But the foulest blot on their character, is the indifference with

which murder is viewed among them. It excites little sensation, excepting

in the family of the person who has been murdered; and

brings, it is said, no disgrace upon him who has committed it ; nor

uneasiness excepting the fear of their revenge. Shall we not hesitate

to assert that human nature is superior to the brute creation, when

we find among this people instances of the fact, that the shedding of

human blood, without the pretext of provocation or offence, and

even by the basest treachery, has fixed no infamy upon the perpetrator

of so awful a crime; and rarely drawn upon him any punishment

from the chief authority ; an authority which the Giver of power

entrusts to mortal hands, only for the protection of the weak and

for the common good?., Suchj at least,1 aretha sentiments which they

express, and such were their replies to my questions on this subject.1

But I will be more careful of the character of this tribe, than they

themselves appear to be : I will not add my own testimony against

them; as I cannot give it from my own knowledge of any fact of

this nature. And although I have heard tales, and have read similar

accusations, yet I hope and believe there may be some foundation

for a better opinion of this people, and that, with respect to murder,

the Bachapins are not actually so depraved a race.

Selfishness and deceit are vices which thrive luxuriantly in this

soil; and,; like rank weeds, smother and destroy other qualities

deserving of cultivation. Avarice has here also taken root, and

grovels along, the ground; but ambition of twofold nature, a virtue

or a vice, a tree of lofty growth, is here unknown. In company with

such characteristics, it cannot be expected that hospitality should

exist, even in sentiment; for, some color of an excuse for neglecting it

in practice, might occasionally be drawn from poverty or the want

of means ; but here the richest individuals use the same language to

exonerate themselves from this duty, as the poorest; they all alike

A FRIENDLY CUSTOM. 5 55

say they are too poor to give. The owner of a hundred cows, after

begging for, and obtaining, a present of tobacco, will, if asked for a

little milk, answer either, Ka kwona maashe (I have not got any milk),

or Maashi kaaio (the milk is all gone).

Yet they have among them a custom, which at first sight has

somewhat of a hospitable appearance; but which on nearer examination

is discovered to be merely an affair of convenience, and much

resembling in principle that of mercantile friendships, which end in

an even balance of accounts. It obtains only, I believe, between

them and the Klaarwater Hottentots, and consists in the selection

of a particular person as the friend from whom they are to procure

whatever they require. These favors are, either returned in kind,

when the other party makes a journey into the country of him whom

he has thus befriended, or they are repaid at the time with a present

of equal value, if the Hottentot be the party who has received them.

Thus, a Hottentot from that village, when he visits Litakun, which

he never does but for the purpose of barter, goes directly to the

house of his correspondent, whom he calls his maat (a Dutch word

identical with, ‘ mate’) who supplies him with milk and assists him

in making his purchases of oxen or ivory, and even engages to secure,

or collect for him, a quantity of these articles ready at the time of his

next visit. From what has been stated of the selfish character of the

Bachapins, it will readily be supposed that this generosity is not intended

as gratuitous, and he does, in fact, receive in tobacco or other

things, what in his estimation is quadruple the value of his trouble,

for on their time, these people set no value. On the other hand, if

the Bachapin visits the Hottentot village, he lives with his * maat’

at free quarters; besides the advantage of accompanying the latter

from Litakun, on which occasions he himself takes no provisions for

their journey. I am unable to say whether this be a general custom

between all the Bichuana tribes; but even so far as it has already

been traced, it is sufficiently interesting, as it exhibits the first dawn

of one of the essential principles of international traffic, and shows

us what mercantile agency is in its infancy, or at its birth.

The character of the Bachapins, as it relates to their natural

4 b 2