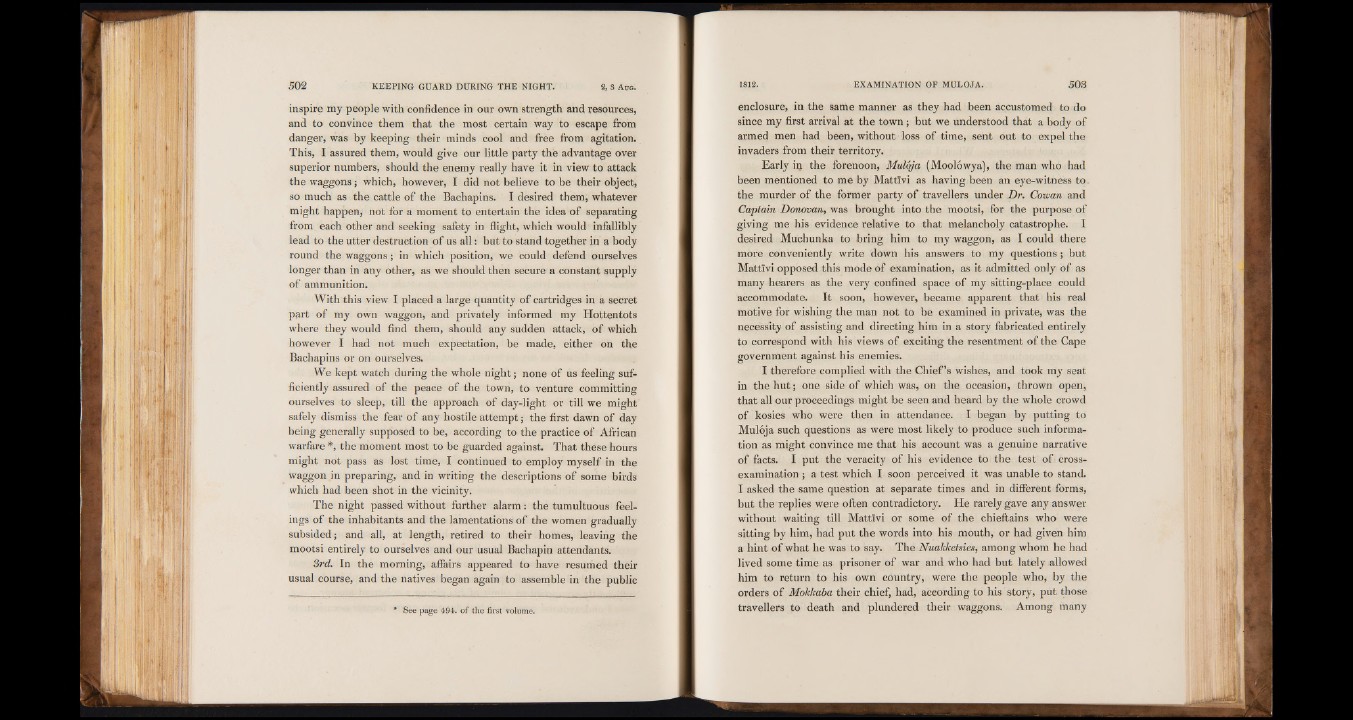

inspire my people with confidence in our own strength and resources,

and to convince them that the most certain way to escape from

danger, was by keeping their minds cool and free from agitation.

This, I assured them, would give our little party the advantage over

superior numbers, should the enemy really have it in view to attack

the waggons; which, however, I did not believe to be their object,

so much as the cattle of the Bachapins. I desired them, whatever

might happen, not for a moment to entertain the idea of separating

from each other and seeking safety in flight, which would infallibly

lead to the utter destruction of us all: but to stand together in a body

round the waggons; in which position, we could defend ourselves

longer than in any other, as we should then secure a constant supply

of ammunition.

With this view I placed a large quantity of cartridges in a secret

part of my own waggon, and privately informed my Hottentots

where they would find them, should any sudden attack, of which

however I had not much expectation, be made, either on the

Bachapins or on ourselves.

We kept watch during the whole night; none of us feeling sufficiently

assured of the peace of the town, to venture committing

ourselves to sleep, till the approach of day-light or till we might

safely dismiss the fear of any hostile attempt; the first dawn of day

being generally supposed to be, according to the practice of African

warfare *, the moment most to be guarded against. That these hours

might not pass as lost time, I continued to employ myself in the

waggon in preparing, and in writing the descriptions of some birds

which had been shot in the vicinity.

The night passed without further alarm: the tumultuous feelings

of the inhabitants and the lamentations of the women gradually

subsided; and all, at length, retired to their homes, leaving the

mootsi entirely to ourselves and our usual Bachapin attendants.

3rd. In the morning, affairs appeared to have resumed their

usual course, and the natives began again to assemble in the public

enclosure, in the same manner as they had been accustomed to do

since my first arrival at the town; but we understood that a body of

armed men had been, without loss of time, sent out to expel the

invaders from their territory.

Early iij the forenoon, Muloja (Moolowya), the man who had

been mentioned to me by Mattlvi as having been an eye-witness to.

the murder of the former party of travellers under Dr. Cowan and

Captain Donovan, was brought into the mootsi, for the purpose of

giving me his evidence relative to that melancholy catastrophe. I

desired Muchunka to bring him to my waggon, as I could there

more conveniently write down his answers to my questions; but

Mattivi opposed this mode of examination, as it admitted only of as

many hearers as the very confined space of my sitting-place could

accommodate. It soon, however, became apparent that his real

motive for wishing the man not to be examined in private, was the

necessity of assisting and directing him in a story fabricated entirely

to correspond with his views of exciting the resentment of the Cape

government 0 aOgainst his enemies. I therefore complied with the Chief’s wishes, and took my seat

in the hut; one side of which was, on the occasion, thrown open,

that all our proceedings might be seen and heard by the whole crowd

of kosies who were then in attendance. I began by putting to

Muloja such questions as were most likely to produce such information

as might convince me that his account was a genuine narrative

of facts. I put the veracity of his evidence to the test of cross-

examination ; a test which I soon perceived it was unable to stand.

1 asked the same question at separate times and in different forms,

but the replies were often contradictory. He rarely gave any answer

without waiting till Mattlvi or some of the chieftains who were

sitting by him, had put the words into his mouth, or had given him

a hint of what he was to say. The Nuakketsies, among whom he had

lived some time as prisoner of war and who had but lately allowed

him to return to his own country, were the people who, by the

orders of Mokkaba their chief, had, according to his story, put those

travellers to death and plundered their waggons. Among many