naturally capable of the higher branches of human knowledge. For,

without any example before us, of a nation of blacks who have risen

to the higher degrees of civilization, such a presumption would be

utterly groundless: it can therefore, at present, rest only on the

wishes of the philanthropist. But, that they may be rendered better

and more reasonable men, by the introduction of a purer system of

morality than that which they are now following, is an assertion

which may be made, without the least hesitation.

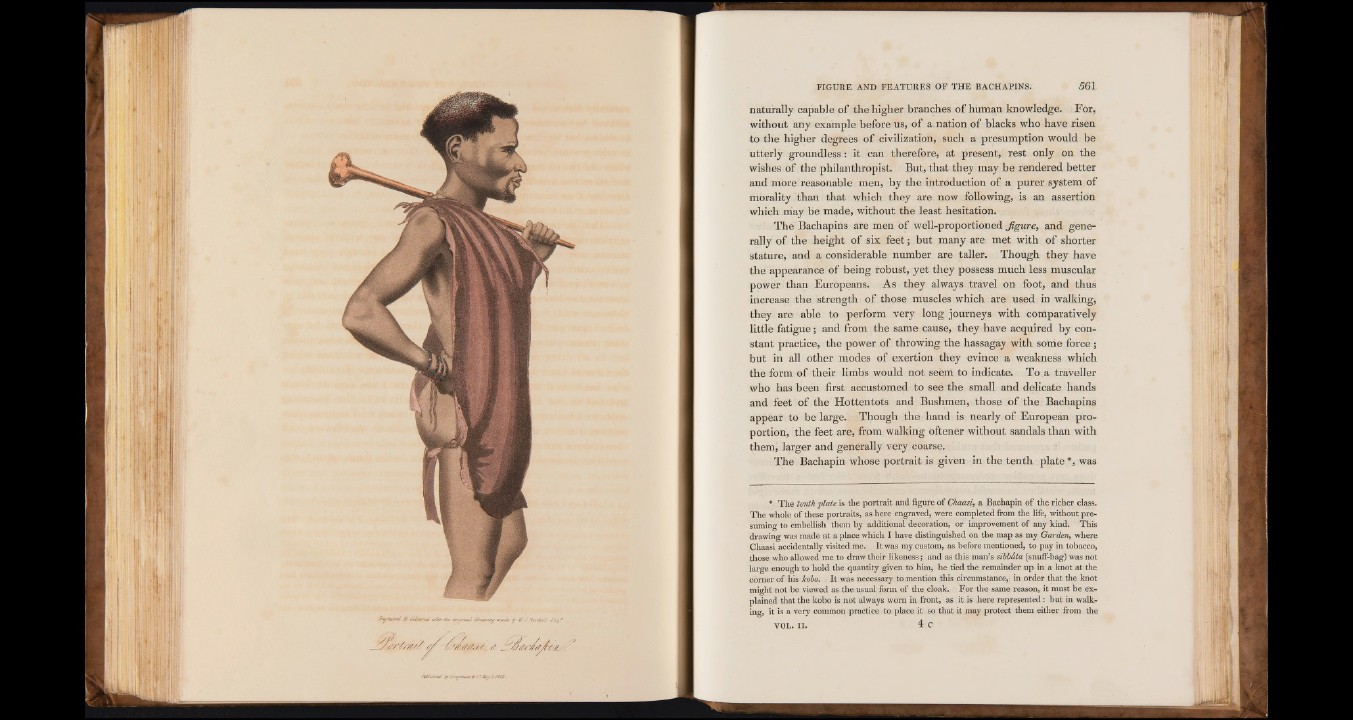

The Bachapins are men of well-proportioned figure, and generally

of the height of six feet; but many are met with of shorter

stature, and a considerable number are taller. Though they have

the appearance of being robust, yet they possess much less muscular

power than Europeans. As they always travel on foot, and thus

increase the strength of those muscles which are used in walking,

they are able to perform very long journeys with comparatively

little fatigue; and from the same cause, they have acquired by constant

practice, the power of throwing the hassagay with some force ;

but in all other modes of exertion they evince a weakness which

the form of their limbs would not seem to indicate. To a traveller

who has been first accustomed to see the small and delicate hands

and feet of the Hottentots and Bushmen, those of the Bachapins

appear , to be large.. Though the hand is nearly of European proportion,

the feet are, from walking oftener without sandals than with

them, larger and generally very coarse.

The Bachapin whose portrait is given in the tenth plate *, was

* The tenth plate is the portrait and figure of Chaasi, a Bachapin of the richer class.

The whole of these portraits, as here engraved, were completed from the life, without presuming

to embellish them by additional decoration, or improvement of any kind. This

drawing was made at a place which I have distinguished on the map as my Garden, where

Chaasi accidentally visited me. It was my custom, as before mentioned, to pay in tobacco,

those who allowed me to draw their likeness; and as this man’s sibbdta (snuff-bag) was not

large enough to hold the quantity given to him, he tied the remainder up in a knot at the

corner of his kobo. It was necessary to mention this circumstance,: in order that the knot

might not be viewed as the usual form of the cloak. For the same reason, it must be explained

that the kobo is not always worn in front, as it is here represented: but in walking,

it is a very common practice to place it so that it may protect them either from the

V O L . I I . 4 c