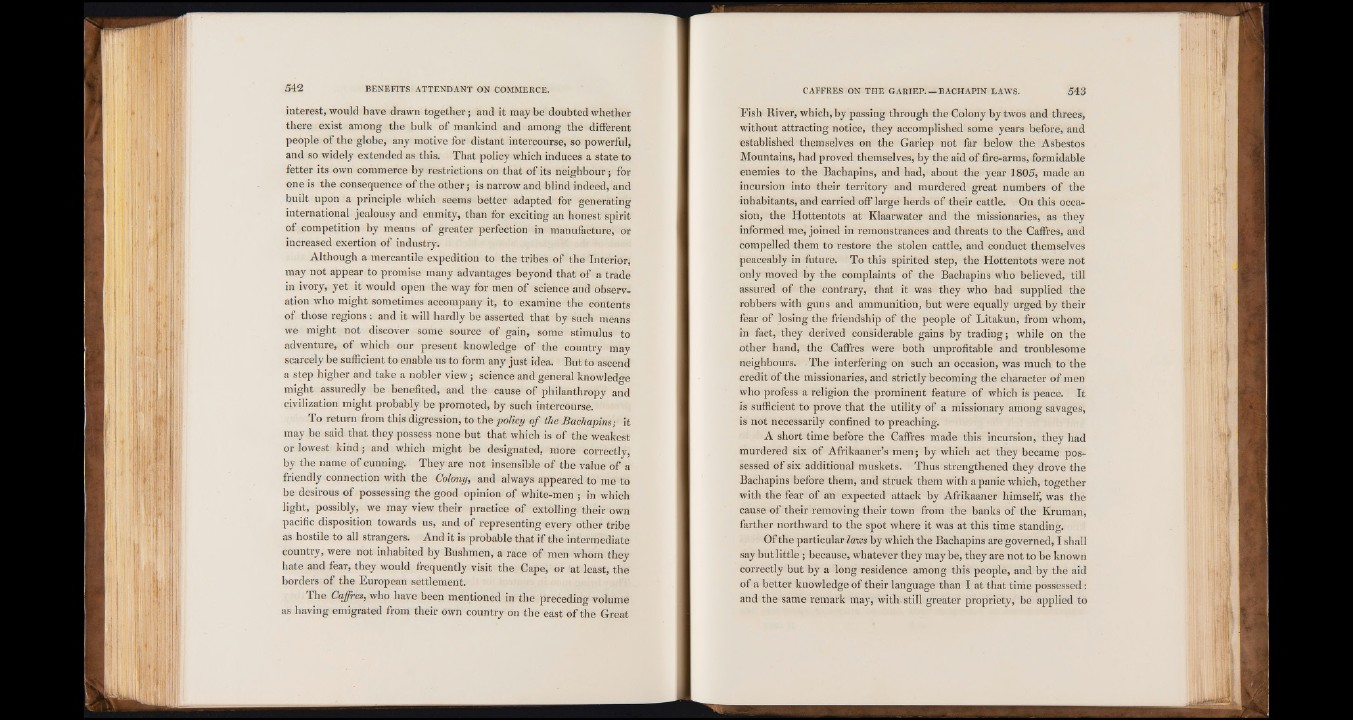

interest, would have drawn together; and it may be doubted whether

there exist among the bulk of mankind and among the different

people of the globe, any motive for distant intercourse, so powerful,

and so widely extended as this. That policy which induces a state to

fetter its own commerce by restrictions on that of its neighbour; for

one is the consequence of the other; is narrow and blind indeed, and

built upon a principle which seems better adapted for generating

international jealousy and enmity, than for exciting an honest spirit

of competition by means of greater perfection in manufacture, or

increased exertion of industry.

Although a mercantile expedition to the tribes of the Interior*

may not appear to promise many advantages beyond that of a trade

in ivory, yet it would open the way for men of science and observation

who might sometimes accompany it, to examine the contents

of those regions: and it will hardly be asserted that by such means

we might not discover some source of gain, some stimulus to

adventure, of which our present knowledge of the country may

scarcely be sufficient to enable us to form any just idea. But to ascend

a step higher and take a nobler view; science and general knowledge

might assuredly be benefited, and the cause of philanthropy and

civilization might probably be promoted, by such intercourse.

To return from this digression, to the policy of the Bachapins; it

may be said that they possess none but that which is of the weakest

or lowest kind; and which might be designated, more correctly,

by the name of cunning. They are not insensible of the value of a

friendly connection with the Colony, and always appeared to me to

be desirous of possessing the good opinion of white-men ; in which

light, possibly, we may view their practice of extolling their own

pacific disposition towards us, and of representing every other tribe

as hostile to all strangers. And it is probable that if the intermediate

country, were not inhabited by Bushmen, a race of men whom they

hate and fear, they would frequently visit the Cape, or at least, the

borders of the European settlement.

The Coffees, who have been mentioned in the preceding volume

as having emigrated from their own country on the east of the Great

Fish River, which, by passing through the Colony by twos and threes,

without attracting notice, they accomplished some years before, and

established themselves on the Gariep not far below the Asbestos

Mountains, had proved themselves, by the aid of fire-arms, formidable

enemies to the Bachapins, and had, about the year 1805, made an

incursion into their territory and murdered great numbers of the

inhabitants, and carried off large herds of their cattle. On this occasion,

the Hottentots at Klaarwater and the missionaries, as they

informed me, joined in remonstrances and threats to the Caffres, and

compelled them to restore the stolen cattle, and conduct themselves

peaceably in future. To this spirited step, the Hottentots were not

only moved by the complaints of the Bachapins who believed, till

assured of the contrary, that it was they who had supplied the

robbers with guns and ammunition, but were equally urged by their

fear of losing the friendship of the people of Litakun, from whom,

in fact, they derived considerable gains by trading; while on the

other hand, the Caffres were both unprofitable and troublesome

neighbours. The interfering on such an occasion, was much to the

credit of the missionaries, and strictly becoming the character of men

who profess a religion the prominent feature of which is peace. It

is sufficient to prove that the utility of a missionary among savages,

is not necessarily confined to preaching.

A short time before the Caffres made this incursion, they had

murdered six of Afrikaaner’s men; by which act they became possessed

of six additional muskets. Thus strengthened they drove the

Bachapins before them, and struck them with a panic which, together

with the fear of an expected attack by Afrikaaner himself, was the

cause of their removing their town from the banks of the Kruman,

farther northward to the spot where it was at this time standing.

Of the particular laws by which the Bachapins are governed, I shall

say butlittle; because, whatever they may be, they are not to be known

correctly but by a long residence among this people, and by the aid

of a better knowledge of their language than I at that time possessed:

and the same remark may, with, still greater propriety, be applied to