11%

m b

tm & B ,

■ H

i s ■

■ llfi i l l m m

I I HMWM

i t ¡ I I I ,.

I

■ I

¡1 1 1

§ 1If! !

Genus OIDEMIA, Flem.

Gen . Chab. Bill swollen or tuberculated at the base, large, elevated, and strong; the tip

mnch depressed and flattened, terminated b y a large flat dertrnm or nail, which has its

extremity rounded and slightly deflected; mandibles laminated, with the plates broad,

strong, and widely set. Nostrils lateral, elevated, oval, placed near the middle o f the bill.

Wings o f mean length, concave; acute. Tail short, graduated, acute. Legs far behind

the centre o f gravity. l o r n short. Feet large; o f four toes, three b efore and one b ehind;

outer toe as long as the middle one, and much longer than the tarsus; hind toe with a

large lobated membrane.

SU RF SCOTER.

Anas perspicillata, Linn.

Oidemia perspicillata, Flem.

Le Canard Marchand.

T his curious Duck should rather be considered as an American species than as strictly indigenous to the

European Continent; it has, however, frequently occurred in the northern seas of this portion of the globe,

and occasionally as far south as the Orkneys and other Scottish islands: we have ourselves received a

specimen (a female) killed in the Firth of Forth. In its general form, economy, and habits, it is intimately

allied to both the Velvet and Scoter Ducks, and the three species have been with good reason separated bv

Dr. Fleming into a distinct genus. No one who has attentively investigated the great family of the Anatidce

can have failed to remark into how many distinct groups or genera even the European examples naturally

arrange themselves, each group being characterized by its diversity of form, habits, and manners. Of these

genera, one of the best defined as well as most conspicuous is that designated Oidemia. The species of this

genus are strictly oceanic, and are expressly adapted for obtaining their food far from shore, being provided

with an entirely water-proof plumage, and endowed with most extraordinary powers of swimming and diving.

Unlike the true Ducks, they seldom visit the inland waters, or feed upon terrestrial mollusca or vegetables,

but keep out at sea, and diving to a very great depth, procure bivalves, mollusca, and submarine vegetables:

they appear to be particularly partial to the common mussel, which we have taken from their throats and

stomachs entire.

It is for the purpose of grinding down this shelly food that the gizzard is not only extremely thick and

muscular, but is also lined with a dense coriaceous cuticle capable of grinding to pulp the hard bodies

subjected to its action. The arctic regions of America appear to be the true habitat of the present species,

particularly about Hudson’s Bay and Baffin's Bay.

Little is known respecting its nidification, but it is said to form its nest near the shore, of grasses lined

with down; and that the eggs are white, and eight or ten in number.

The wings are short, convex, and pointed, and although they afford the bird tolerable powers of flight, they

are equally adapted for an organ of progression under water, an element to which, rather than to the air,

it frequently trusts for safety.

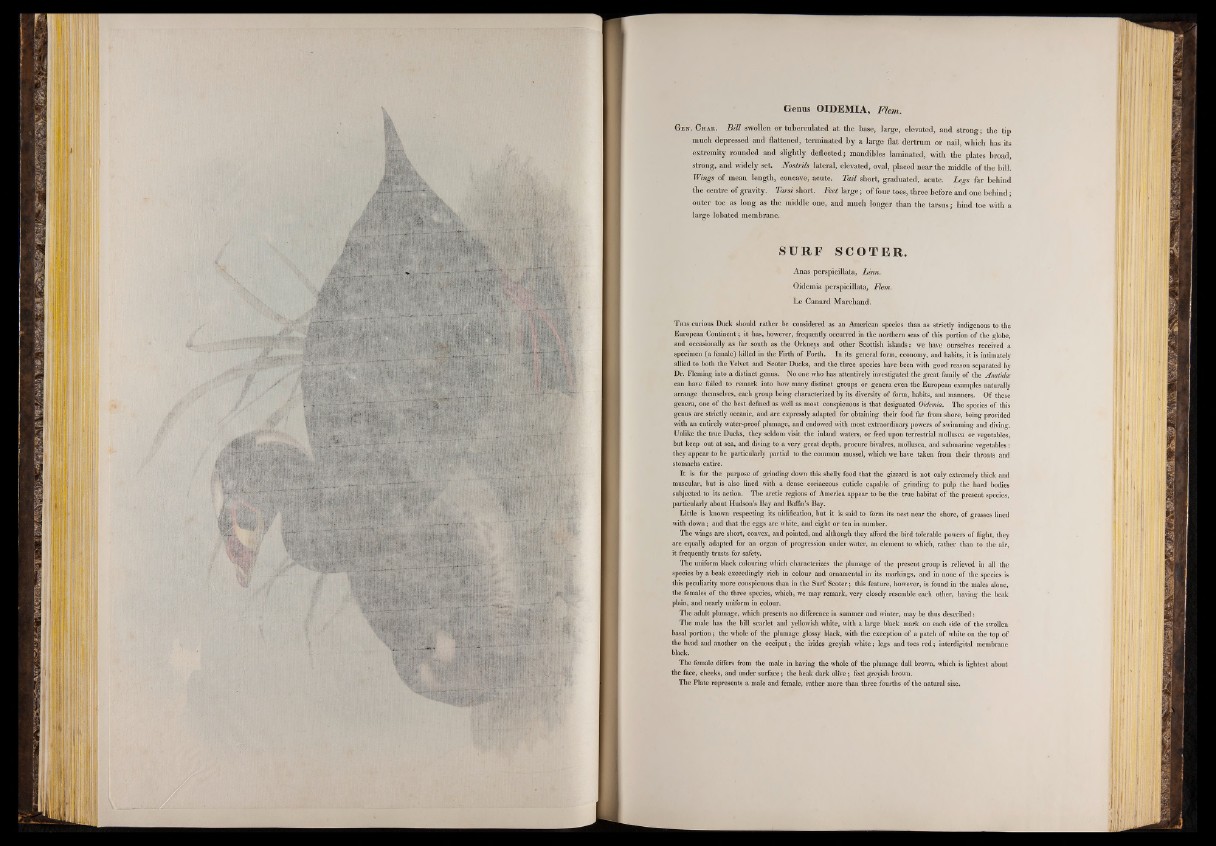

The uniform black colouring which characterizes the plumage of the present group is relieved in all the

species by a beak exceedingly rich in colour and ornamental in its markings, and in none of the species is

this peculiarity more conspicuous than in the Surf Scoter; this feature, however, is found in the males alone,

the females of the three species, which, we may remark, very closely resemble each other, having the beak

plain, and nearly uniform in colour.

The adult plumage, which presents no difference in summer and winter, may be thus described:

The male has the bill scarlet and yellowish white, with a large black mark on each side of the swollen

basal portion; the whole of the plumage glossy black, with the exception of a patch of white on the top of

the head and another on the occiput; the irides greyish white; legs and toes red; interdigital membrane

black.

The female differs from the male in having the whole of the plumage dull brown, which is lightest about

the face, cheeks, and under surface; the beak dark olive; feet greyish brown.

The Plate represents a male and female, rather more than three fourths of the natural size.