R A Z O R -B I L L E D AUK.

Alca torda, Linn.

, Le Pingoin macropt&re.

T h e habits and manners of the Razor-bill so closely approximate to those of the Common Guillemot (Uria

Troile, Linn.), that the same description equally applies to both; to enter into them fully would therefore be

only repeating what we have said in our account of the last-mentioned bird: like it, the Razor-bill inhabits the

wide expanse of the ocean, the severities of which it braves with the utmost indifference; indeed it appears

to rejoice in the agitation of the billows, that brings around it multitudes of small fish, which constitute its

only support; like it, the Razor-bill, when called upon by the impulse of nature to the great work of incubation,

seeks the inaccessible cliffs round the coasts of our island, on which it assembles in immense flocks, to

deposit each its single egg on the barren ledges of the rock; and so often do the eggs of the two species

resemble each other, that they are scarcely to be distinguished except by a practical observer: that of the

Razor-bill is somewhat less, and generally has neither the grotesque marking nor the deep green colour which

characterize the greater portion of the eggs of the Guillemot. The Razor-bill is very generally distributed

throughout the seas of the arctic circle, a portion of the globe of which it is more especially a native; never,

we believe, extending its migrations beyond the temperate latitudes of Europe in the Old World, and the

southern portions of the United States in the New. In point of numbers the Razor-bill does not appear to

equal its ally, if we may judge by what is to be observed along our own shores: the Guillemots literally swarm

during the breeding-season on most of the rocky shores not only of our island but of the northern portions

of the Continent in general. The dissimilarity which exists in the beak of the young from that of the fully

adult Razor-bill has been the source of no little confusion, and has given rise among ornithologists to

synonyms which were erroneously bestowed as specific titles on the young of the year, before the bird had

been duly developed, a circumstance which does not take place until the second year: this mistake was

further strengthened by the total absence o f the white line between the eye and the beak, in birds whose

size is equal to that of adults. It is, however, a singular fact, that when just excluded from the egg, this

white line is strikingly apparent on the down with which they are then clothed; but with the acquisition of

the feathers, this white line disappears, and is regained with the stripes on the upper mandible towards the

close of the second year.

During winter the adults of both sexes lose the dusky colouring of the throat precisely in the same

manner as the Guillemot. At this period the old and young closely resemble each other in plumage, and are

only to be distinguished by the character of the beak.

The sexes are alike in colouring.

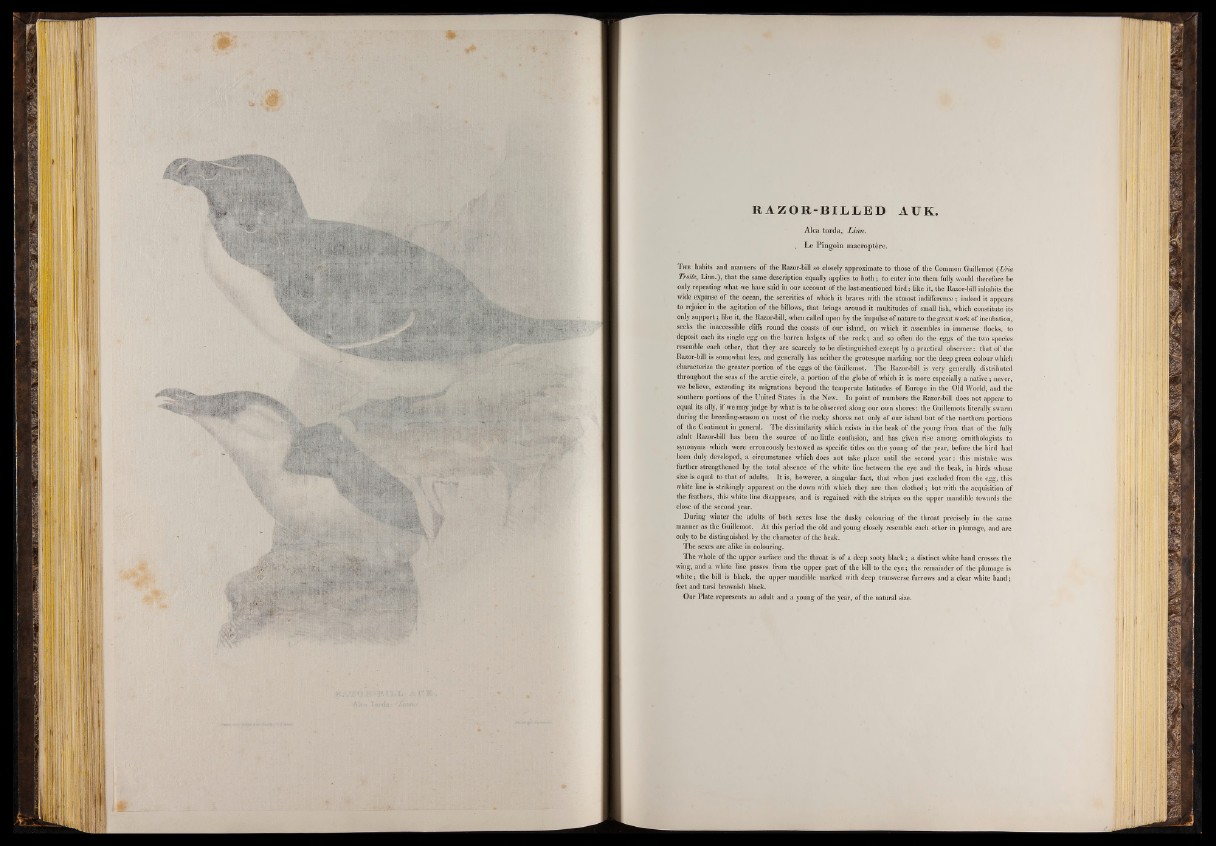

The whole of the upper surface and the throat is of a deep sooty black; a distinct white band crosses the

wing, and a white line passes from the upper part of the bill to the eye; the remainder of the plumage is

white; the bill is black, the upper mandible marked with deep transverse furrows and a clear white band;

feet and tarsi brownish black.

Our Plate represents an adult and a young of the year, of the natural size.