38 GEOGRAPHICAL DISTEIBIJTION.

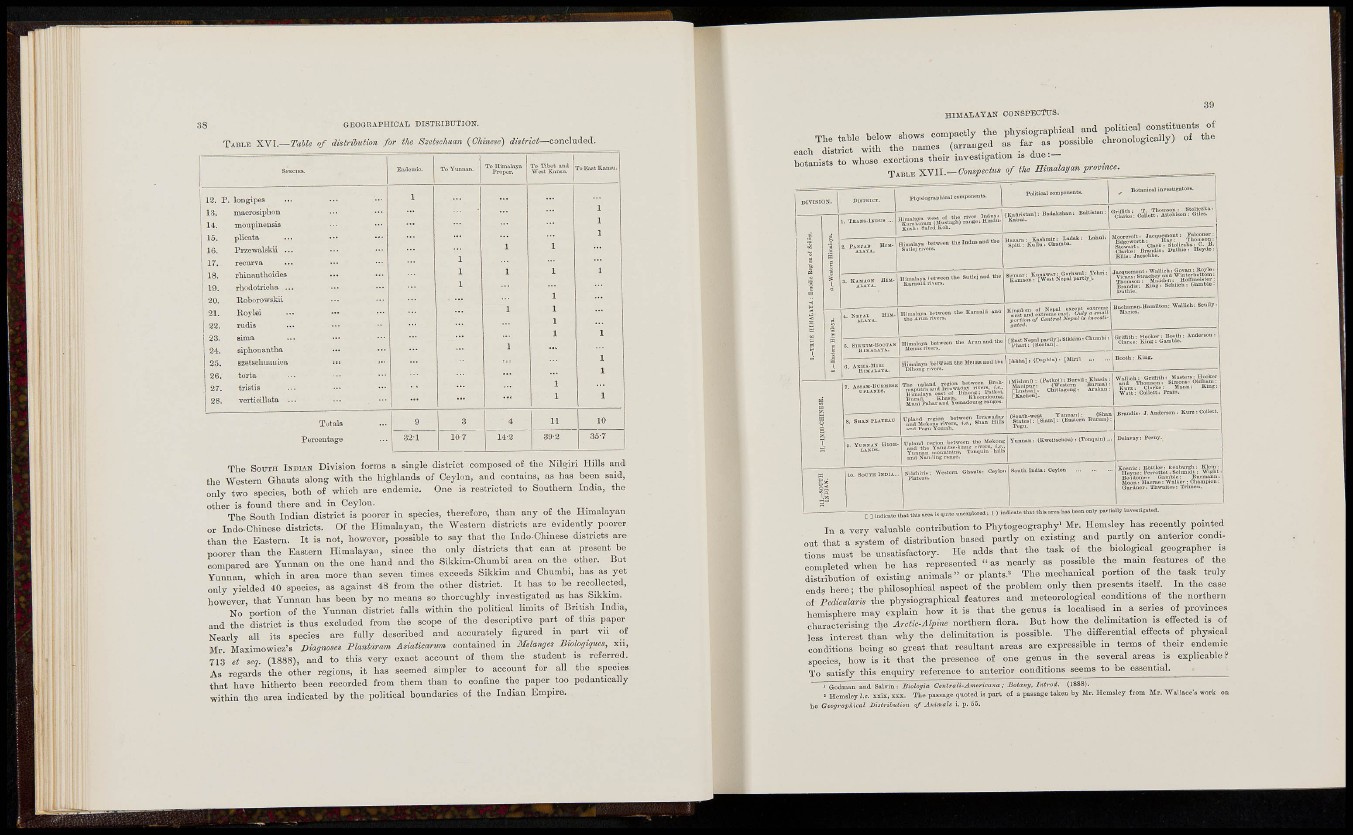

TABLE XVI. Table of distributim for tlie S^eiachmii {Chinese) ¿ISFRICI—eoncluiled.

To mmalftj-Piuijur. a WToo at krtnaanud. j^E^tKamu

12. P. loDgipes

13.

14. moupinensia

15. plicftta

16. pKewftlskii ...

17. recurva

18. rbinantboides

19. rhodotriclia ...

20. Rotorowskii

21. Roylei

I 22. rudis

23. sima

24. siphonantlia

25. szetscliuauica

26. torta

27. tristis

28. verticillata ..

Totals

Percentage

T h e SOOTH IIDIAH Division forms a single district composed oi the Nilgiri Hills and

t h e Western Ghants along with the highlands of Ceylon, and contains, as has been said,

only two species, both of which are endemic. One is restricted to Southern India, the

other is found there and in Ceylon. , , ,

Tho South Indian district is poorer in species, therefore, than any of the Himalayan

or Indo-Chinese districts. Of the Himalayan, the Western districts are evidently poorer

t h a n the Eastern. It is not, however, possible to say that the Indo-Chmese districts are

poorer than the Eastern Himalayan, since the only districts that can at present be

L m p a r e d are Yunnan on the one hand and the Sikkim-Chumbi area on the other. But

Yunnan which in area more than seven times exceeds Sikkim and Ohumbi, has as yet

only yielded 40 species, as against 48 from the other district. It has to be recollected,

however that Yunnan has beon by no means so thoroughly investigated as has Sikkim.

N o ' o o r t i o n of the Yunnan district falls within the political limits of British India,

and the district is thus excluded from the scope of the descriptive part of this paper

Nearly all its species are fully desorlbod and accurately figured m part vn of

Mr Maximowicz's Plantaram Adatieamm contained in Melange! Biolostque!,, xii,

713 et seq (1888), and to this very exact account of thom the student is referred.

As regards the other regions, it has seemed simpler to account for all the spccies

t h a t have hitherto been recorded from them than to confine the paper too pedantically

within the area indicated by the political boundaries oi the Indian Empire.

oy

HIMAIATAN COSSPECT0S.

each d««"» inve s t iga t ion is dne: -

1J ..'iisr«;;:^.—.....i.™«; < > — » - ' > " • — - » — > » " •

I n a very valuablo contribntion to Pbytogeography' Mr. Hem,ley has recently pointed

out that a system of distribution based partly on existing and partly on anterior conditions

must be nnsatisfactory. He adds that the task of the biological geographer is

completed when he has represented "as nearly as possible the mam features of the

distribution of existing animals" or plants.' The mechanical portion of the task truly

ends here- the philosophical aspect oi the problem only then presents itself. In the ease

of PedieJam the physlographical features and meteorological conditions of the northern

hemisphere may explain how It Is that the genus is localised in a series of provinces

characterising the Arctic-Alfiue northern flora. But how the delimitation is efi^ected is of

tess interest than why the delimitation is possible. The differential effects of physical

conditions being so great that resultant areas are expressible in tei-ms of their endemic

species, how is it that the presence of one genus in the several areas is exphcable?

To satisfy this enquiry reference to anterior conditions seems to be essential.

' eodmttn and Salvin: Jliotosia CentralisAmerUana ,• Botany, Intmd. (1888).

= Henislcy U. xsLi, sxs. The passage quoted is part of a passage taken bj Mr. Hcmsley from Mr. Wallace's work on

lie Geogre^iical Jlietribiitwti of Aminals i, p. Bo.