MORPHOLOGT.

Tl,e lut a and the basal part of the hood are of tho sao,o texture, and are more deUcatc

t h a n t h e hp,wh.ch turn , thinner than the hood proper with ;hich the beak then

present un.ior™. The only exoeption to this is in the A»ODO»T.,=, whero hood and lip

are of the same consistonoo as the tube. In the corolla as a whole thero are all ™daf

ons from the greatest dehcaoy (P. Kino», gracüi¿)io a sub-eoriaceo„s texture (P. fr«».

The nerves of the tube are parallel and pass into both lip and hood. In particular

spccies the nervation is highly constant, and in ti.e lip may consist of one central

nerve with lateral nervales for each lobe, of one contral main nervo in the midlobe

and three main nerves m each lateral lobe, or of throe main nerves in every lobe The

central mam nerves branch to both sides; the lateral main nerves, moro especially'of the

n„d obe branch to tho outside only as a rule, though sometimes .11 three nerves in each

o the th„e lobes branch ,„ both directions. The secondary nervales always anastomose,

« o„gh Of en not very visibly; sometimes, however, the anastomosis gives a character^

istio areolate appearance to the lip (P. SaiJuma). The nerve in the tube that corresponds

to the insertion of the posterior stamen on each side does not pass vertically

upwards into the hood, bnt arches forward and ends in the margin at the point which

indicates the junction of the base with tho hood proper. As a rule, this nerve simply

disappears m the thickened margin, but sometimes (P. npU„n,U, oiontoph„,) it is

prolonged as the median nerve of a distinct tooth; at other times (P. lon,iMa, furfu-

. • « „ ) It IS lost at the base of a distinct sinuation. This nerve gives off from its upper

convex aspect a series of parallel branches that form, along with the prolonged nerL

of the ube posterior to the two arching nerves, the nervo system of the hood proper

and, if It be present, of the beak also. ^^

Steven long ago observed that in many species with a spicato infloresconee the

who e eoi.,lla is obliquely twisted, so that a spiral arrangement of the ñoivers is the

result and that m almost all the species known to him the lip is oblique. Marimowic.

too, has observed m living specimens that in some species tho whole corolla, but moré

especially the hood, is twisted de.trorsely (with the sun), tho lip at the same timi

b o i n . oblique, but without n..ing whether the upper surface of t L lip look, towarl

or IS averted from the sun. Nothing can be said definitely of obliquity of lip in dried

specimens, but as regards the hood the twisting is very evident, even in the Lrbarium

Sometimes It involves both tube and hood (P. „ „ ( / „ ) ; at other times it is confined

t o he hood ( P . The significance of this phenomenon is worthy of study in tho

field ; the morphological result and the arrangements by which it is effected are canable

of interpretation, in the case of the LOHMKOSTBES at all events, and if a sufficient

number of flowers bo examined, oven in the herbarium. Whatever the arrangement may

b e the result is in every case the sanie-tho removal of the apex of the beak, and alon.

w i t h that tho stigma, from the lip, which is presumably the platform inviting insect visit"

ants to the flower. One arrangement which effects the result is mot with in the flexuose'

beaked ORTHoaKHVNOHJ! (P. r^timtu). Here the flower does not open till the beak is

f u l ly elongated. The apex of tho beak is at the margin of the midlobe of the lip- tlio

terminal convoluted portion oE the beak is lodged in this lobe, tho portion behind being

straight. While the flexuous portion is being developed in this conflned space, it becomos

as a matter of accommodation, twisted on its own long axis, and this twist'beoomin»

permanently impressed on tho beak, causes its apex, and along with it the stigma, to b¡

12), instead of turned towards it (Plate áa, f. 1)

i not all. The elongating beak tends to push tho

ivorted from tho lip (Plate 23,

when the flower opens. But th

wicz, Mel. BiaL i, 776.

COLOEÍTIO.N.- 11

whole lip downwards, and at the same time towards the side on which the overlapping,

and therefore most easily displaced, lateral lobe lies. This being usually the left side,

t h e thrust of the beak is downwards and towards the left. But there is thus an

equal and opposite counter-thrust upwards and to the right acting upon the hood.

And since the basal portion of the hood is of a more delicate texture than either

t h e hood proper or the lip, the chief result is a certain amount of twisting to the

right at that place as the point of least resistance. But although this is one, it is

not the only, and indeed can scarcely be the usual, explanation of dextrorse twisting.

Other notable means of attaining the same result occur among the SiPHONANrH^.

In P. megalaiiUm the lateral lobe of the lip overlapped by the other grows more

slowly.^ This prevents the growth of the hood in an erect position. Being thus deflected

in the unexpanded flower, the hood retains this attitude when the flower opens. Sometimes

the apex of the beak remains permanently entangled in this dwarfed lateral lobe.

The apex of the beak also becomes averted from the lip by the unequal development

of the margin and of the rest of the hood. Not infrequently (P. Elwesii) the margin

grows most rapidly, and thus, by throwing back the dorsum of the hood, at the same time

tilts tile apes of the beak upwards and away from the lip. More remarkable still is

t h e arrangement that occurs in P. hicomuta. Here the growth of the margin of the hood

is arrested while that of the rest proceeds. The result is exactly what is seen when

the string that closes the month of a canvas money-bag is tightened. The basal portion

of the hood, especially in the vicinity of the margin, is thrown into many plaits and

folds, and these now deflect, now reverse, now invert the upper portion—in every case

removing the tip of the beak, and with it the stigma, from the neighbourhood of the lip.

The colour of the corolla varies from a pale or rose pink (P. furfuracm) to dark purple

( P . iriUgrifoliii); or from green (P. fragilis\ or dil-ty white (P. fycnanUm), to yellow (P.

Ssulhjm'i); a few spocies are pure white ( P . alhijlom). Stated in the most general terms, the

colour is either some shade of red or some shade of yellow, corollas of both types giving rise,

either as sports or permanently, to white. At the same time a species may be red in one

locality and yellow in another (P. myriophyUa, megalantha, altaica), but this is not very usual.

Red is slightly the more common of tho two, 151 of the species, or 57-8 per cent, of

t h e whole, being of this colour. There is, besides, a marked association of red colour with

t h e character of opposite leaves, and an equally marked association with the presence of

a beak. These correlations with structure are, however, probably indirect, and depend

rather on geographical distribution. Tlio subjoined table exhibits the facts of tho case

more compactly (tho colour of four species being doubtful) :—

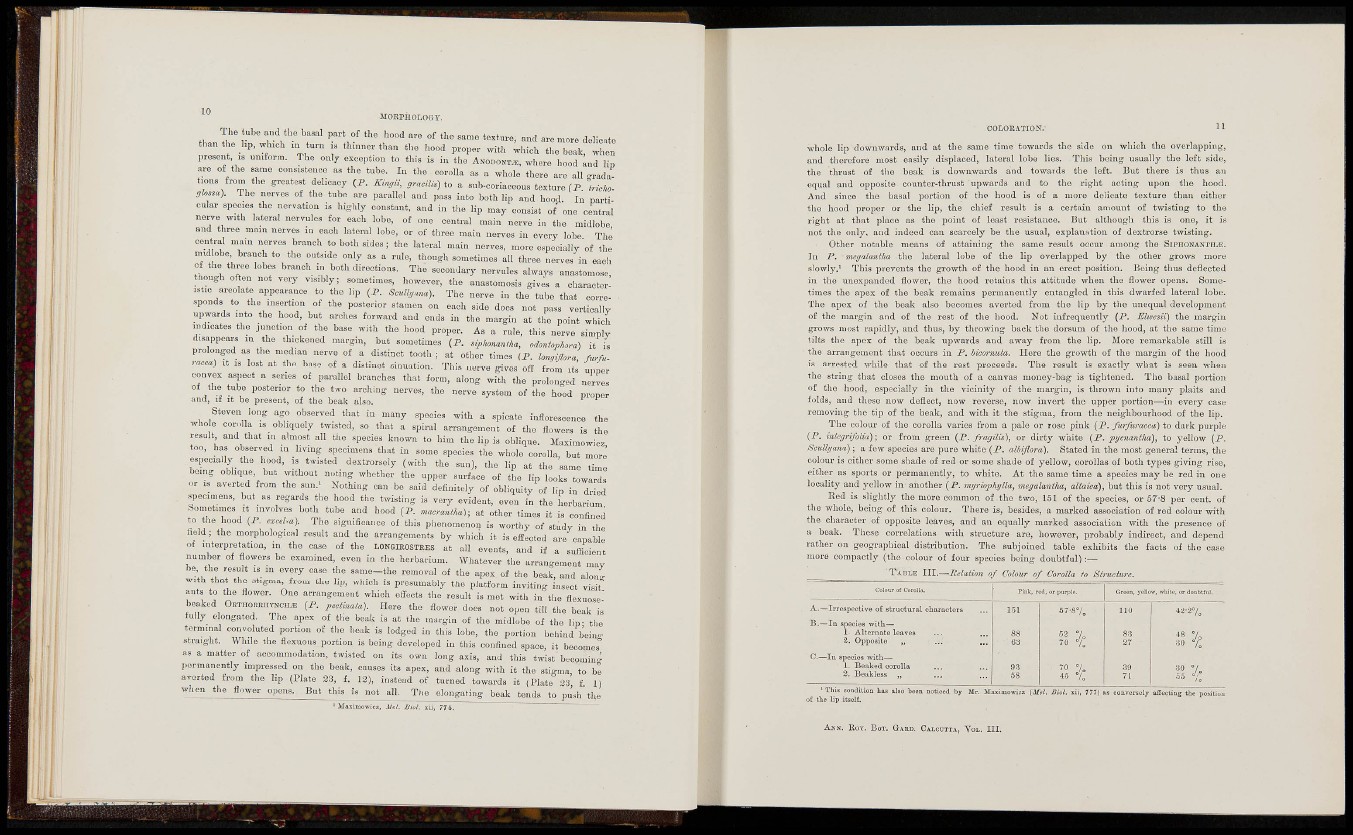

T.IBLI! lll.—Rdalion of Colour of Corolla to Structure.

Colour of Corolln. Pink, r, 3d. or pur,)!,.. Green, yoUow, wl lite, or doubtftil,

A. I I Tespectiv© of structural characters 1ÖI 5 7 - 8 7 „ 110

B . - I I 1 species -witli—

i Alternate leaves 8 8 5 2 7C 8 3 4 8 "U

2. Opposite „ 6 3 7 0 t 2 7 C. - I D . species -with—

1. Beaked corolla 9 3 " 0 7, 3 9 -30 7

2 . Beakless „ 5 8 4 5 7O 7 1 5 5

Í i.Md. Biol. Eii, 777) a ersely affectiug the iiQsiliou

AKN. KOY. BOT. a.\BD. CALCUTr.^v, YOL. n i .