CHAPTER VI

SUPERSTITIONS

T h e eastern Bhotias erect shrines, called Saithans,

for their gods in some quiet place outside the village,

or in a grove or by the road side in a shady nook, and

in their devotions wholly dispense with the services

of the priesthood, some elder of position taking the

leading part.

The western Bhotias employ Brahmans as priests,

and are year by year being further enmeshed in the

toils of Hindu ceremonial ritual, while the low caste

Bhotias of all parts of Bhot universally employ the

sister s son for all priestly functions. The Saithan, or

god’s place, is a little chamber a yard in length and the

same in breadth and one or two yards in height, in

which there is a white stone, viz., the familiar

“ ling, and on the top of which there is a small

branch of a tree adorned with narrow strips of

white cloth (Daja) which flutter in the wind. However,

most frequently we find no shrine, but instead

a simple stone, and by it a prayer-pole or Darcho

(a tree trunk with a few branches left on the top)

fixed in the ground with streamers (Daja) floating

from it. The general form of worship consists in the

cooking of cakes or rice, and preparation of dough cones

or “ dalangs,” which are offered with liquor. The

“ dalang ” is so typical of all Bhotia ceremonies that

it merits description. Sattoo or flour is made from

parched grain, and this sattoo is worked into a cone of

dough one and a half feet high, pointed at .the top

and large at the bottom, and from the sides of this cone

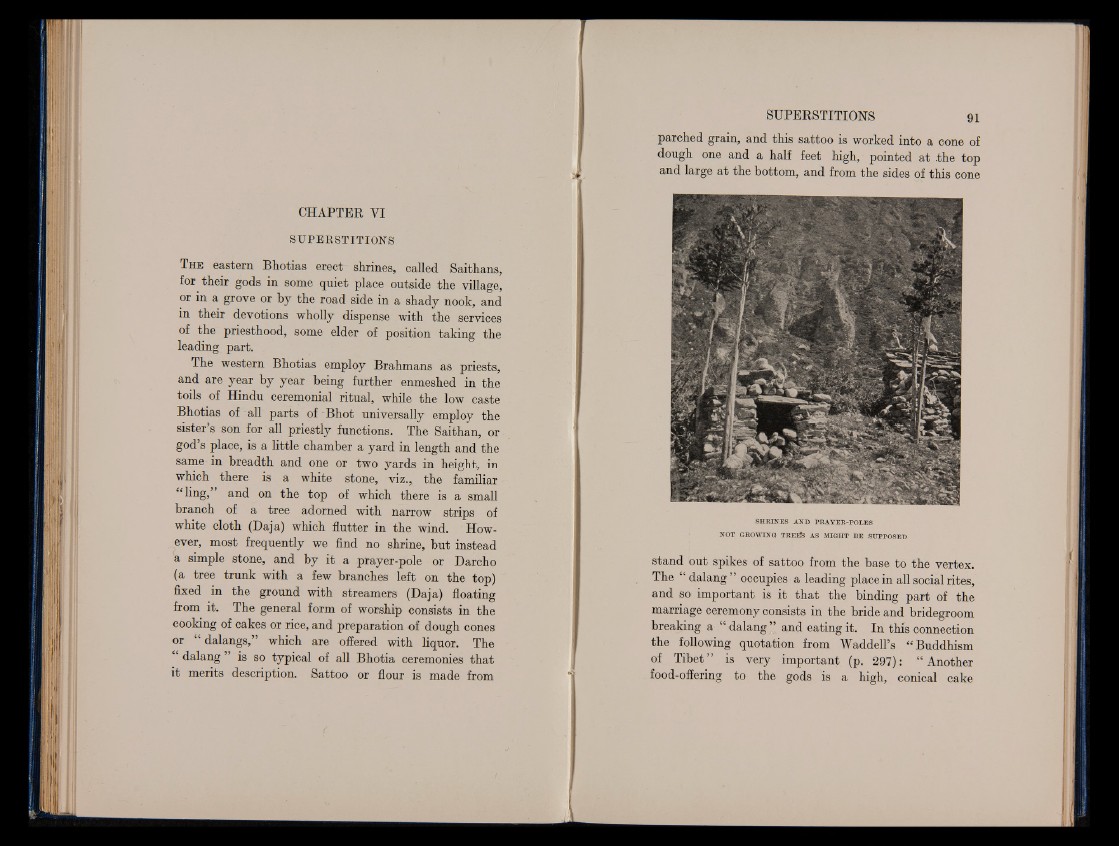

SHRINES AND PRAYER-POLES

NOT GROWING TRE1Î3 AS MIGHT BE SUPPOSED

stand out spikes of sattoo from the base to the vertex.

The “ dalang” occupies a leading place in all social rites,

and so important is it that the binding part of the

marriage ceremony consists in the bride and bridegroom

breaking a “ dalang ” and eating it. In this connection

the following quotation from Waddell’s “ Buddhism

of Tibet” is very important (p. 297): “ Another

food-offering to the gods is a high, conical cake