eaten by all Tibetans in these parts and is much prized

for food. Bhotias are in the stage of betwixt and

between: those who are non-Hinduised eat it readily,

while those who are taking to themselves the respectability

of Hinduism consider it as sacred and to be

avoided at all costs.

Eowls are not to be found anywhere and consequently

eggs are unobtainable—not that the Tibetans of these

parts have any religious or social scruples against

the keeping of poultry, like many high caste Hindus,

but apparently they find the climatic difficulties insuperable.

The Jongpen of Taklakot started a poultry-

farm which prospered during the warm weather, but

in the winter . the fowls’ feet were frozen off and

they became cripples. One cannot help feeling, that

with a little effort difficulties might be overcome, for

the cold is not more severe than in Canada, where

poultry-farming flourishes, but it is just in this quality

of enterprise that the Tibetan of Western Tibet is

lacking. He has the most perfect country for road-

making, immense level plains, no gradients and a

small rainfall, and practically all he has to do is to

remove the stones on one side and a splendid road is

made; but this small amount of energy he is unequal

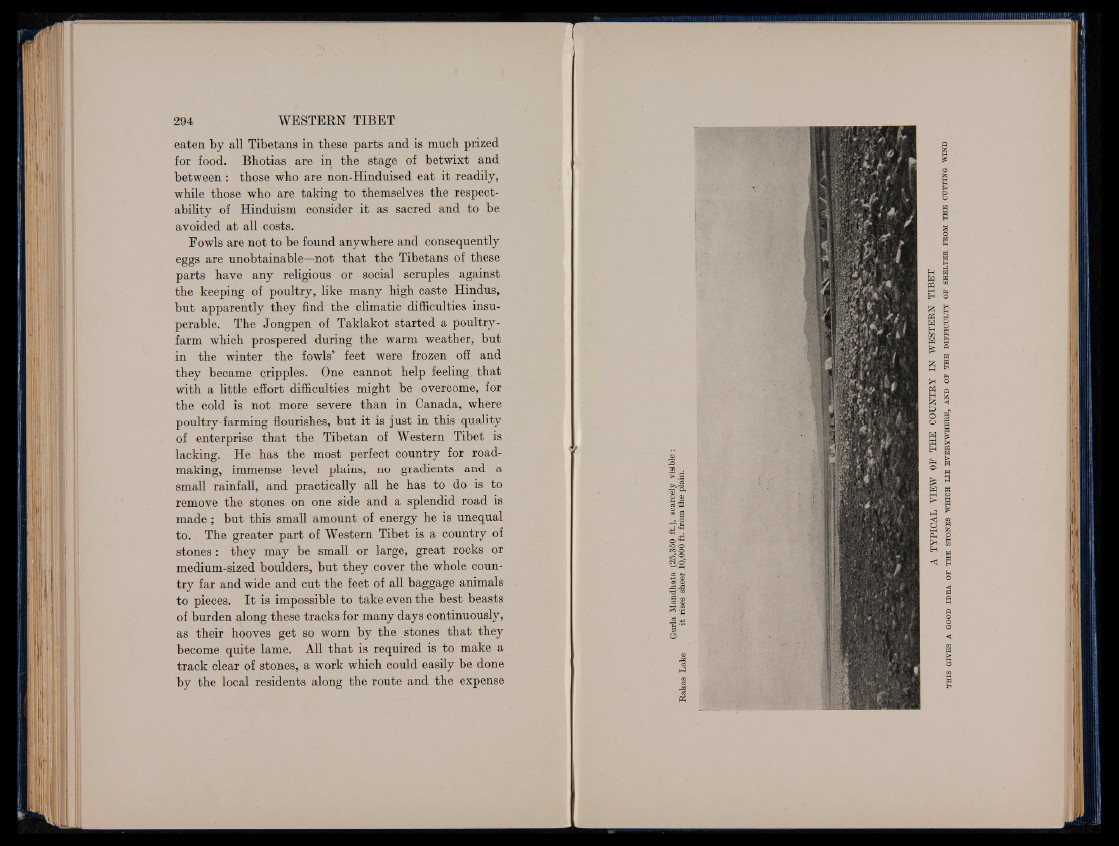

to. The greater part of Western Tibet is a country of

stones: they may be small or large, great rocks or

medium-sized boulders, but they cover the whole country

far and wide and cut the feet of all baggage animals

to pieces. I t is impossible to take even the best beasts

of burden along these tracks for many days continuously,

as their hooves get so worn by the stones that they

become quite lame. All that is required is to make a

track clear of stones, a work which could easily be done

by the local residents along the route and the expense

Gurla Mandhata (25,350 ft.), scarcely visible:

Rakas Lake it rises sheer 10,000 ft. from the plain.