traveller, but the nomadic spirit seems to be unquenchable,

and nothing will keep them in one place long.

They are here one day and gone the next, and nobody

knows their movements. Nor can they ever forget their

royal descent. When we parted ours were the only

salutations.

As we left Askot the Raj bar was very anxious for Long-

staff to give his professional advice about a stroke of

paralysis which had overtaken his uncle, the father

of Karak Sing. The old man was placed under the

shade of a tree on the road, and Longstaff very carefully

overhauled him and explained at length the exact

working of the electric battery, which Karak Sing had

very dutifully bought, and which must have cost a large

sum as it was a good one. The scene was a pretty one.

A large crowd of villagers watched the application of

this European cure, and, of course, little boys and girls

were crawling everywhere where they should not, and

in the centre sat the dignified old man in his dandy,

with the Raj bar standing by his side, while Western

science was explained to sons, who with gentle hands

applied the battery: and all around us the grand

mountains towered overhead, and the surging river

Kali rushed on its course.

As we began our descent to the river we very soon

felt the heat, for the road descends to the glacial stream

of the Gori, and then runs along a hot, confined valley

to the junction of this river with the Kali. This spot

of the junction is a particularly sacred one, and in winter,

i.e., when the water in the Kali is low, there is a small

bridge built across the river to enable traders to pass,

and devotees to frequent the shrine which stands on

the narrow tongue of land between the two rivers. Our

British boundary on the Nepalese side is the Kali river,

which is known as the Sarda in the plains, and over the

entire length of its course, except near its source, the

Kali is unfordable, being throughout a tearing, raging

torrent. The only suspension bridge, which was built

by the British, is at a spot some thirty miles below

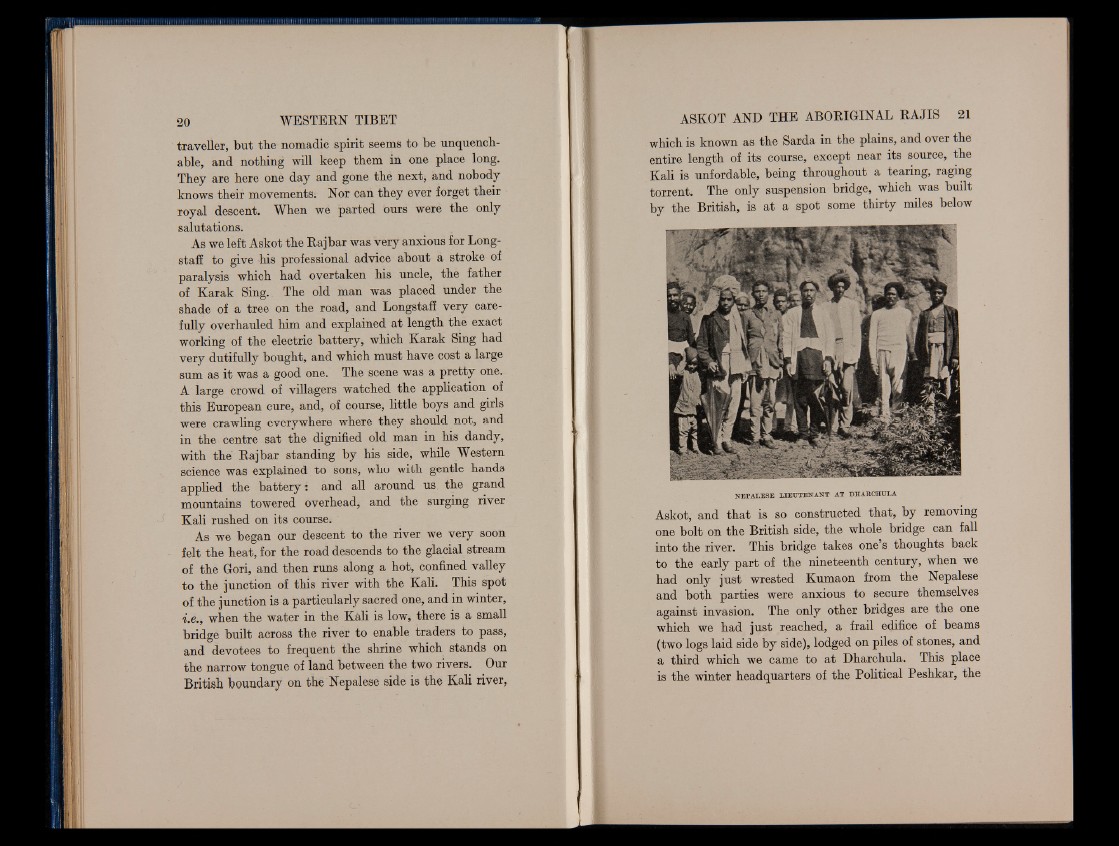

NE PAL E SE LIEUT ENA NT AT DHARCHULA

Askot, and that is so constructed that, by removing

one bolt on the British side, the whole bridge can fall

into the river. This bridge takes one’s thoughts back

to the early part of the nineteenth century, when we

had only just wrested Kumaon from the Nepalese

and both parties were anxious to secure themselves

against invasion. The only other bridges are the one

which we had just reached, a frail edifice of beams

(two logs laid side by side), lodged on piles of stones, and

a third which we came to at Dharchula. This place

is the winter headquarters of the Political Peshkar, the