future transmigration), whether in their mild type or

in their character of angry or ferocious gods; they

do not attach any particular sanctity to the lotus

flower, nor do they use the prayer-wheel; nor are. the

Tibetan tutelary or country gods, local gods and genii

represented by them in the terrifying shape of idols

and pictures so general in Tibet. The peculiar service

of the Lamas, vividly recalling the gorgeous ritual of

Roman Catholicism, composed as it is of prayers,

wearing of sumptuous vestments, adoration of images,

ringing of bells, burning of candles on terraced altars,

dispensing the so-called Eucharist of Lamaism, the

elements being consecrated bread and wine, or the

weird rites resembling the Mumbo Jumbo worship of

Africa, viz., wearing of horrible masks, devil-dancing,

drinking of blood in human skulls, using trumpets of

human bones and other uncanny ceremonial, are not

found among the Bhotias at all, nor have they priests,

or Lamas, to interpret the Tibetan faith. As for the

Tibetan shibboleth “ Om Mani Padme Hung ”—

“ H a il! Jewel of the Lotus flower (the Dalai Lama)

H a il! ”—which is universally repeated in Tibet and,

without which, and the prayer-wheel, the spiritual

life of that country would apparently come to a standstill—

it is not even known in Bhot, and certainly no

special efficacy is attached to it. Had they ever been

incited by the desire to imitate the Tibetans, there is

no doubt that they could have found the means to do

so, but we find that they have preferred an exactly

opposite line of conduct. I t is true that the Bhotias,

when visiting or trading in Tibet make a point of

worshipping the deities of that country, no doubt

in order to make quite sure that their spiritual affairs

have received every possible advantage, and similarly

they reverence the gods of Hinduism when they descend

to the lower country inhabited by Hindus, but they

do not bring these gods of the outside countries into

their own. This statement must be a little modifieri

now that they are beginning to call themselves Hindus,

and to adopt the customs and manners of Hindus.

But still the visible objects of their religion and their

ritual are of the simplest.

Landon in his “ Lhasa ” * writes of Central Tibet:

“ Invariably there will be found outside a house

four things. The first is the prayer-pole or the

horizontal sag of a line of moving squares of gauze;

the second is a broken teapot of earthenware from

which rises the cheap incense of burnt juniper twigs—

a smell which demons cannot abide; the third, a nest

of worsted rigging, shaped like a cobweb and set about

with coloured linen tags, catkins, leaves, sprigs and

little blobs of willow often crowning the skull of a dog

or sheep. The eyes are replaced by hideous projecting

balls of glass and a painted crown-vallary

rings it round. Hither the spirits of disease within

the house are helplessly attracted, and small-pox, the

scourge of Tibet, may never enter there. Last of [all

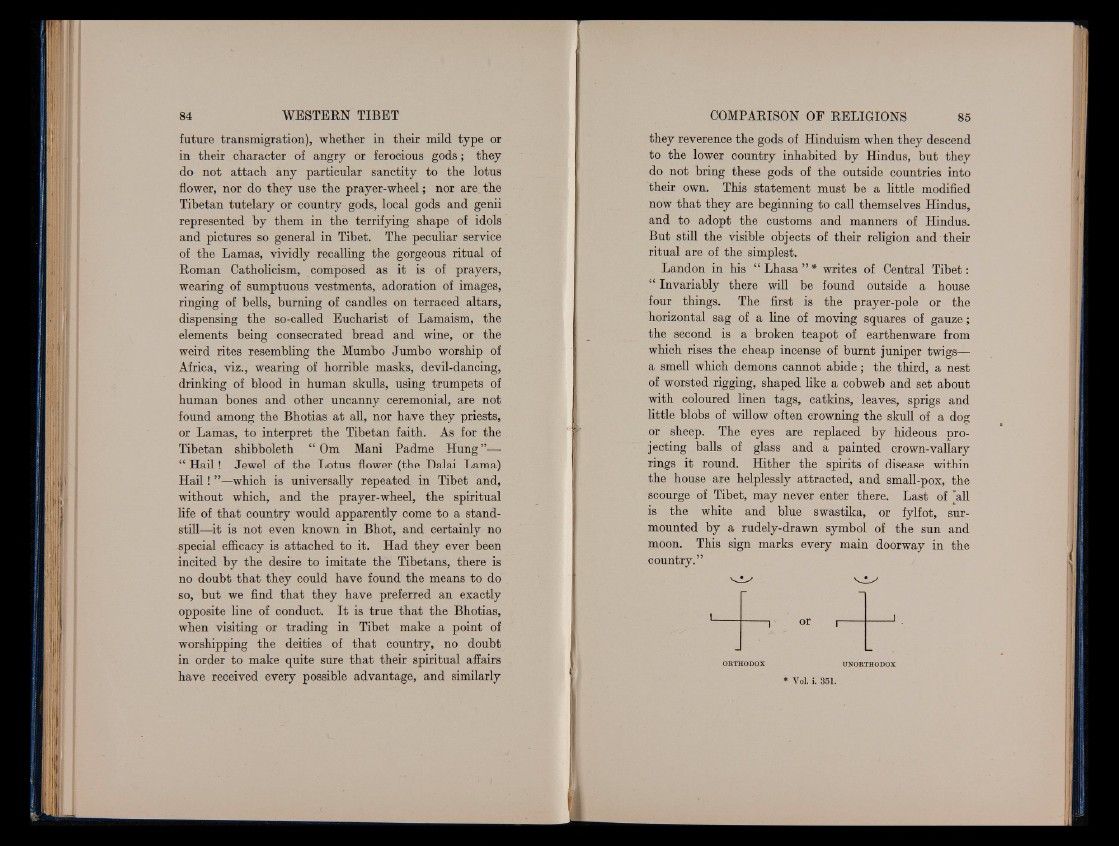

is the white and blue swastika, or fylfot, surmounted

by a rudely-drawn symbol of the sun and

moon. This sign marks every main doorway in the

country.”

or

ORTHODOX UNORTHODOX

* V o l. i. 3 5 1 .