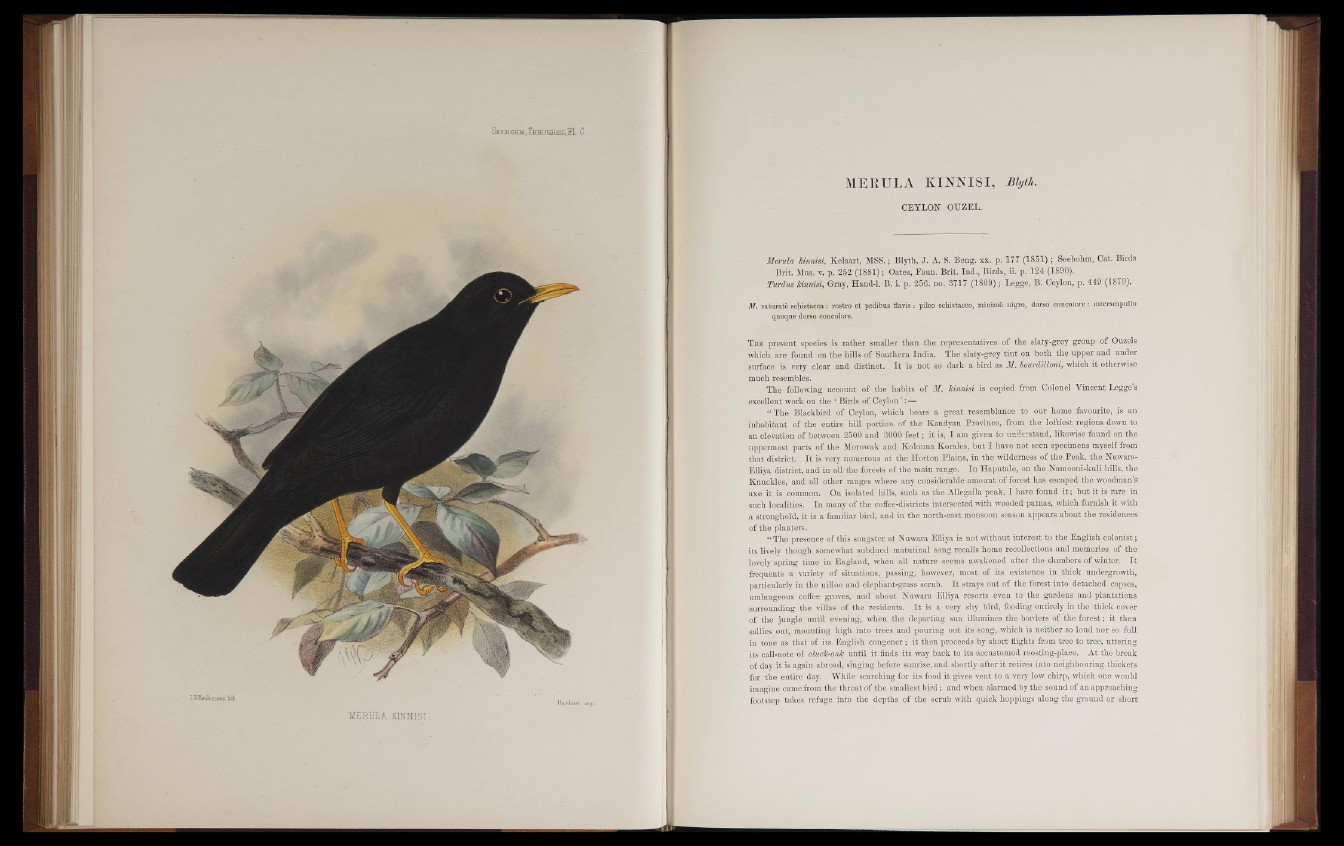

M E R U L A K IN N I S I , Blyth.

CEYLON OUZEL.

Merula kinnisi, Kelaart, MSS.; Blyth, J. A. S. Beng. xx. p. 177 (1851); ¿Seebohm, Cat. Birds

Brit. Mus. v. p. 252 (1881); Oates, Faun. Brit. Ind., Birds, ii. p. 124 (18Q0).

Turdus kinnisi, Gray, Hand-1. B. i. p. 256. no. 3717 (1869); Legge, B. Ceylon, p. 449 (18/9).

M. saturate schistacea: rostro e t pedibus flavis : pileo schistaceo, minime nigro, dorso concolore: interscapulio

quoque dorso concolore.

T h e present species is rather smaller than the representatives of the slaty-grey group of Ouzels

which are found on the hills of Southern India. The slaty-grey tint on both the upper and under

surface is very clear and distinct. I t is not so dark a bird as M. bourdilloni, which it otherwise

much resembles.

The following account of the habits of M. kinnisi is copied from Colonel Vincent Legge’s

excellent work on the * Birds of Ceylon’

“ The Blackbird of Ceylon, which bears a great resemblance to our home favourite, is an

inhabitant of the entire hill portion of the Kandyan Province, from the loftiest regions down to

an elevation of between 2500 and 3000 fe e t; it is, I am given to understand, likewise found on the

uppermost parts of the Morowak and Kolonna Korales, but I have not seen specimens myself from

that district. I t is very numerous at the Horton Plains, in the wilderness of the Peak, the Nuwara-

Elliya district, and in all the forests of the main range. In Haputale, on the Namooni-kuli hills, the

Knuckles, and all other ranges where any considerable amount of forest has escaped the woodman’s

axe it is common. On isolated hills, such as the Allegalla peak, I have found it; but it is rare in

such localities. In many of the coffee-districts intersected with wooded patnas, which furnish it with

a stronghold, it is a familiar bird, and in the north-east monsoon season appears about the residences

of the planters.

“ The presence of this songster at Nuwara Elliya is not without interest to the English colonist;

its lively though somewhat subdued matutinal song recalls home recollections and memories of the

lovely spring time in England, when all nature seems awakened after the slumbers of winter. I t

frequents a variety of situations, passing, however, most of its existence in thick undergrowth,

particularly in the nilloo and elephant-grass scrub. I t strays out of the forest into detached copses,

umbrageous coffee groves, and about Nuwara Elliya resorts even to the gardens and plantations

surrounding the villas of the residents. I t is a very shy bird, feeding entirely in the thick cover

of the jungle until evening, when the departing sun illumines the borders of the forest; it then

sallies out, mounting high into trees and pouring out its song, which is neither so loud nor so full

in tone as that of its English congener; it then proceeds by short flights from tree to tree, uttering

its call-note of cluck-onk until it finds its way back to its accustomed roosting-place. At the break

of day it is again abroad, singing before sunrise, and shortly after it retires into neighbouring thickets

for the entire day. While searching for its food it gives vent to a very low chirp, which one would

imagine came from the throat of the smallest bird ; and when alarmed by the sound of an approaching

footstep takes refuge into the depths of the scrub with quick hoppings along the ground or short