Prognathism

—method of

determining.

Objections

to Flower’s

index.

to the horizontal in which the skull is oriented. Since the Frankfort-Munich plane,

i. e. that passing through the upper part of the external auditory meatus and the

infra-orbital margin, has no direct association with any of the angles of the aforesaid

triangle, it becomes a matter of extreme difficulty to orient the triangle in relation to

this plane, more particularly since the Frankfort-Munich plane is based on points which

lie lateral to the mesial plane, and has no constant relation to points which fall within

the mesial plane.

The alveolo-condylic plane of Broca, whilst referable to points in the mesial plane,

i. e. the alveolar point, is open to the grave objection that the whole orientation of the

skull depends on the development of the upper facial area; in other words, when the

face is proportionately long, the whole skull when oriented in this plane acquires an

upward tilt and the disposition of the calvaria is correspondingly altered, which is not

necessarily the case, as may be readily proved. These difficulties, however, are in great

part overcome if the skull is so oriented that the basi-nasal line is disposed at an angle

of 2 70 with the horizontal; the nasion then becomes the point below and in front of which

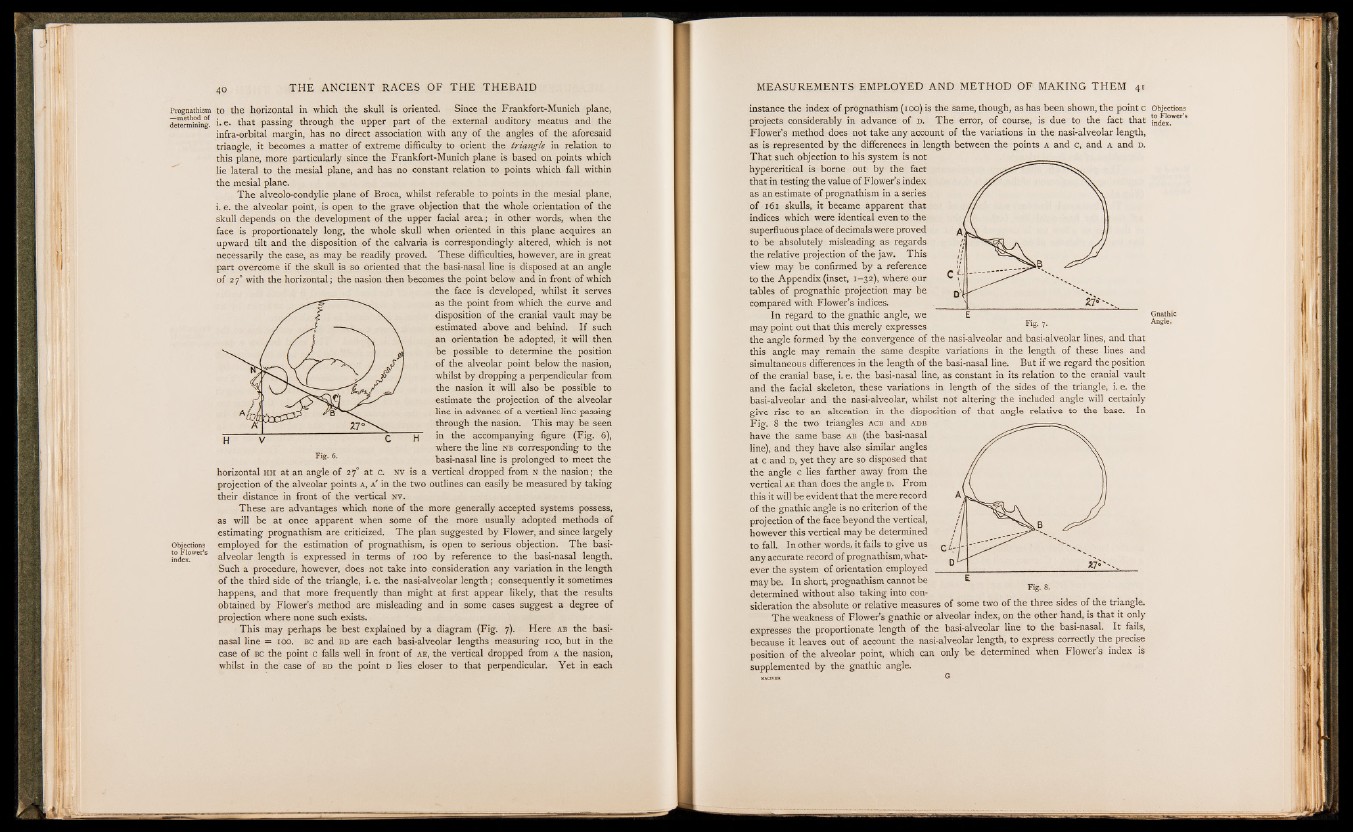

the face is developed, whilst it serves

as the point from which the curve and

disposition of the cranial vault may be

estimated above and behind. If such

an orientation be adopted, it will then

be possible to determine the position

of the alveolar point below the nasion,

whilst by dropping a perpendicular from

the nasion it will also be possible to

estimate the projection of the alveolar

line in advance of a vertical line passing

through the nasion. This may be seen

in the accompanying figure (Fig. 6),

where the line n b corresponding to the

basi-nasal line is prolonged to meet the

horizontal h h at an angle of 270 at c. n v is a vertical dropped from n the nasion; the

projection of the alveolar points a , a ' in the two outlines can easily be measured by taking

their distance in front of the vertical n v .

These are advantages which none of the more generally accepted systems possess,

as will be at once apparent when some of the more usually adopted methods of

estimating prognathism are criticized. The plan suggested by Flower, and since largely

employed for the estimation of prognathism, is open to serious objection. The basi-

alveolar length is expressed in terms of 100 by reference to the basi-nasal length.

Such a procedure, however, does not take into consideration any variation in the length

of the third side of the triangle, i. e. the nasi-alveolar length ; consequently it sometimes

happens, and that more frequently than might at first appear likely, that the results

obtained by Flowers method are misleading and in some cases suggest a degree of

projection where none such exists.

This may perhaps be best explained by a diagram (Fig. 7). Here a b the basi-

nasal line = 100. b c and b d are each basi-alveolar lengths measuring 100, but in the

case of b c the point c falls well in front of a e , the vertical dropped from a the nasion,

whilst in the case of b d the point d lies closer to that perpendicular. Yet in each

instance the index of prognathism (10 0) is the same, though, as has been shown, the point c Objections

projects considerably in advance of d . The error, of course, is due to the fact that S

Flower s method does not take any account of the variations in the nasi-alveolar length,

as is represented by the differences in length between the points a and c, and a and d .

That such objection to his system is not

hypercritical is borne out by the fact

that in testing the value of Flower’s index

as an estimate of prognathism in a series

of 161 skulls, it became apparent that

indices which were identical even to the

superfluous place of decimals were proved

1

to be absolutely misleading as regards

the relative projection of the jaw. This

view may be confirmed by a reference

to the Appendix (inset, 1-32), where our

1

tables of prognathic projection may be

DT .—^

compared with Flower’s indices.

27"''-..

F ig . 7.

Gnathic

Angle.

In regard to the gnathic angle, we

may point out that this merely expresses

the angle formed by the convergence of the nasi-alveolar and basi-alveolar lines, and that

this angle may remain the same despite variations in the length of these lines and

simultaneous differences in the length of the basi-nasal line. But if we regard the position

of the cranial base, i. e. the basi-nasal line, as constant in its relation to the cranial vault

and the facial skeleton, these variations in length of the sides of the triangle, i. e. the

basi-alveolar and the nasi-alveolar, whilst not altering the included angle will certainly

give rise to an alteration in the disposition of that angle relative to the base. In

Fig. 8 the two triangles a c b and a d b

have the same base a b (the basi-nasal

line), and they have also similar angles

at c and d , yet they are so disposed that

the angle c lies farther away from the

vertical a e than does the angle d. From

this it will be evident that the mere record

of the gnathic angle is no criterion of the

projection of the face beyond the vertical,

however this vertical may be determined

to fall. In other words, it fails to give us

any accurate record of prognathism, whatever

the system of orientation employed

may be. I n short, prognathism cannot be

determined without also taking into consideration

27'

F ig . 8.

the absolute or relative measures of some two of the three sides of the triangle.

The weakness of Flower’s gnathic or alveolar index, on the other hand, is that it only

expresses the proportionate length of the basi-alveolar line to the basi-nasal. It fails,

because it leaves out of account the nasi-alveolar length, to express correctly the precise

position of the alveolar point, which can only be determined when Flower’s index is

supplemented by the gnathic angle.

I i

Il II