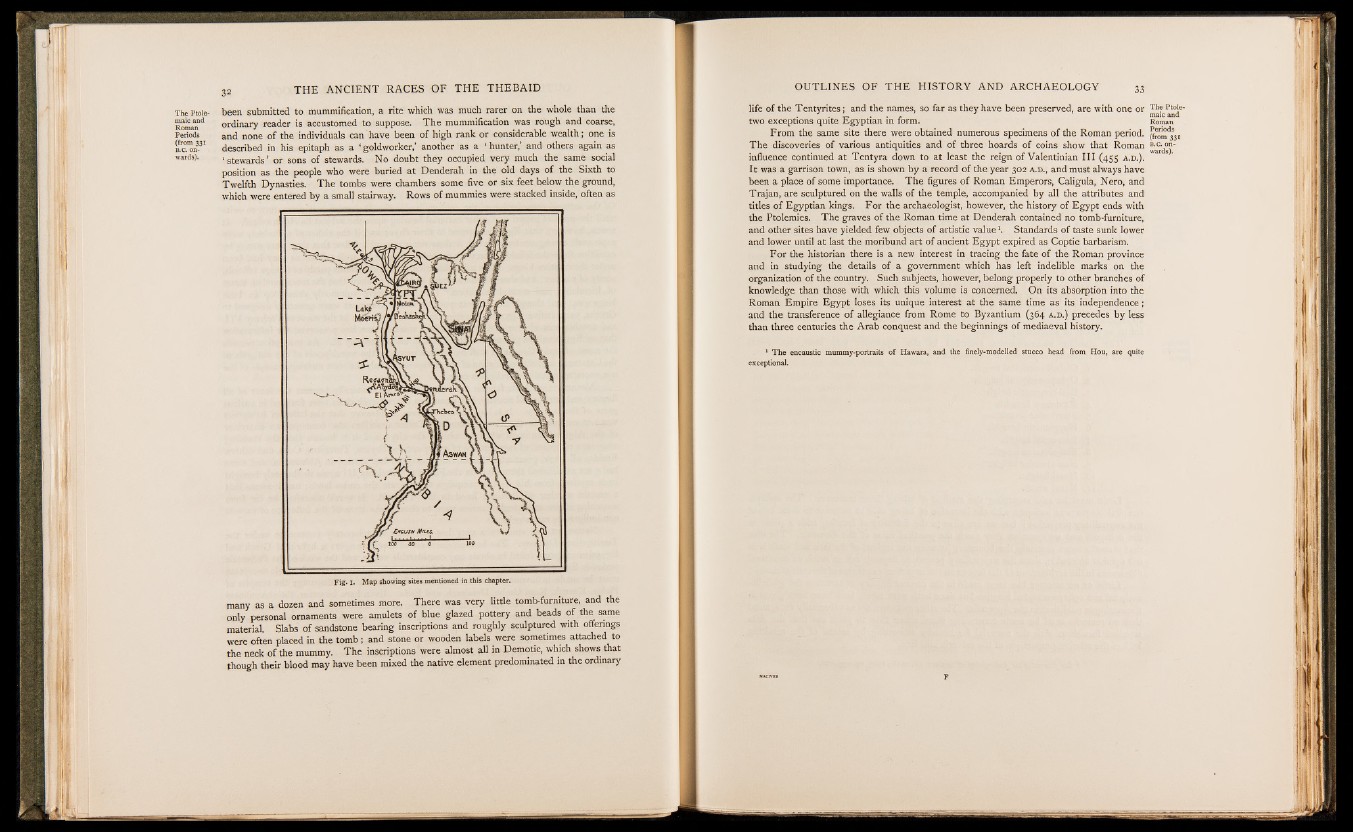

The Ptolemaic

and

Roman

Periods

(from 331

b.c. onwards).

been submitted to mummification, a rite which was much rarer on the whole than the

ordinary reader is accustomed to suppose. The mummification was rough and coarse,

and none of the individuals can have been of high rank or considerable wealth; one is

described in his epitaph as a ‘ goldworker,’ another as a ‘ hunter, and others again as

‘ stewards’ or sons of stewards. No doubt they occupied very much the same social

position as the people who were buried at Denderah in the old days of the Sixth to

Twelfth Dynasties. The tombs were chambers some five or six feet below the ground,

which were entered by a small stairway. Rows of mummies were stacked inside, often as

many as a dozen and sometimes more. There was very little tomb-furniture, and the

only personal ornaments were amulets of blue glazed pottery and beads of the same

material. Slabs of sandstone bearing inscriptions and roughly sculptured with offerings

were often placed in the tomb; and stone or wooden labels were sometimes attached to

the neck of the mummy. The inscriptions were almost all in Demotic, which shows that

though their blood may have been mixed the native element predominated in the ordinary

life of the Tentyrites; and the names, so far as they have been preserved, are with one or

two exceptions quite Egyptian in form.

From the same site there were obtained numerous specimens of the Roman period.

The discoveries of various antiquities and of three hoards of coins show that Roman

influence continued at Tentyra down to at least the reign of Valentinian III (455 a .d .).

It was a garrison town, as is shown by a record of the year 302 a .d ., and must always have

been a place of some importance. The figures of Roman Emperors, Caligula, Nero, and

Trajan, are sculptured on the walls of the temple, accompanied by all the attributes and

titles of Egyptian kings. For the archaeologist, however, the history of Egypt ends with

the Ptolemies. The graves of the Roman time at Denderah contained no tomb-furniture,

and other sites have yielded few objects of artistic value \ Standards of taste sunk lower

and lower until at last the moribund art of ancient Egypt expired as Coptic barbarism.

For the historian there is a new interest in tracing the fate of the Roman province

and in studying the details of a government which has left indelible marks on the

organization of the country. Such subjects, however, belong properly to other branches of

knowledge than those with which this volume is concerned. On its absorption into the

Roman Empire Egypt loses its unique interest at the same time as its independence;

and the transference of allegiance from Rome to Byzantium (364 a.d.) precedes by less

than three centuries the Arab conquest and the beginnings of mediaeval history.

1 T h e encaustic mummy-portraits o f Hawara, and the finely-modelled stucco head from Hou, are quite

exceptional.

The Ptolemaic

and

Roman

Periods

(from 331

B.c. onwards).