Orientation points which approach either the assumed vertical or horizontal. Unfortunately the

obtain a true adoption of Huxley’s system involves making a mesial section of the skull, and though

the^ro^ec- *n manY instances there may be no objection to such procedure, yet it must be borne

tionPofthe" in mind that oftentimes, when dealing with skulls of great age, it is difficult enough

to preserve the crumbling remains intact without proceeding to apply the saw.

Cleland, in 1870*, following on the same lines, proposed a modification of the above

method. His base line, which extends from the opisthion to the nasion, included three

parts— a middle part corresponding pretty nearly with Huxley’s ‘ basi-cranial axis,’ an

anterior portion corresponding to the length of the orbit, and a posterior including the

length of the foramen magnum. In dealing with Cleland’s base it was necessary to note

the angle formed by each of the above divisions with the others. There, again, in order

to do so it was necessary to bisect the skull longitudinally.

Owing to the great morphological importance of the basi-cranial axis it seemed

to us of the utmost advantage to utilize this part of the cranium as a base on which

to compare the development and form of the brain capsule dorsally, as well as the

variations in shape of the facial skeleton ventrally.

1 P h il. T ra n s. 1870.

To do so, however, without entailing the division of the skull, necessitated the

addition of portion of the ethmo-vomerine region to the basi-cranial axis, the two combined obtain a true

corresponding to the entire length of the basi-nasal line. With the view of determining the™rojec-

whether such a method was likely to prove useful certain observations were made. fi°e°fhiS

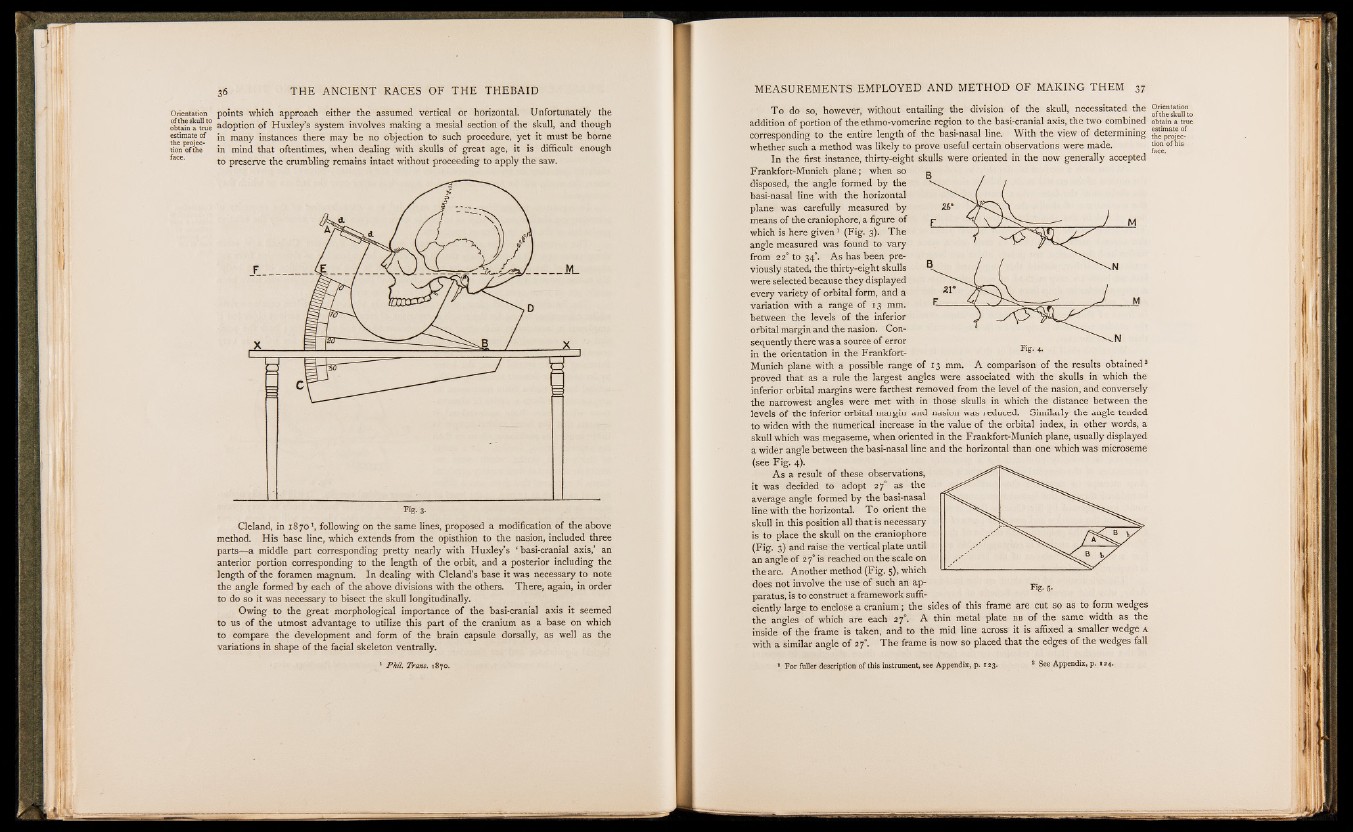

In the first instance, thirty-eight skulls were oriented in the now generally accepted

Frankfort-Munich plane; when so

disposed, the angle formed by the

basi-nasal line with the horizontal

plane was carefully measured by

means of the craniophore, a figure of

which is here given1 (Fig. 3). The

angle measured was found to vary

from 220 to 340. As has been previously

stated, the thirty-eight skulls

were selected because they displayed

every variety of orbital form, and a

variation with a range of 13 mm.

between the levels of the inferior

orbital margin and the nasion. Consequently

there was a source of error

in the orientation in the Frankfort-

Munich plane with a possible range of 13 mm. A comparison of the results obtained2

proved that as a rule the largest angles were associated with the skulls in which the

inferior orbital margins were farthest removed from the level of the nasion, and conversely

the narrowest angles were met with in those skulls in which the distance between the

levels of the inferior orbital margin and nasion was reduced. Similarly the angle tended

to widen with the numerical increase in the value of the orbital index, in other words, a

skull which was megaseme, when oriented in the Frankfort-Munich plane, usually displayed

a wider angle between the basi-nasal line and the horizontal than one which was microseme

(see Fig. 4).

As a result of these observations,

it was decided to adopt 270 as the

average angle formed by the basi-nasal

line with the horizontal. To orient the

skull in this position all that is necessary

is to place the skull on the craniophore

(Fig. 3) and raise the vertical plate until

an angle of 2 70 is reached on the scale on

the arc. Another method (Fig. 5), which

does not involve the use of such an apparatus,

is to construct a framework sufficiently

large to enclose a cranium; the sides of this frame are cut so as to form wedges

the angles of which are each 270. A thin metal plate bb of the same width as the

inside of the frame is taken, and to the mid line across it is affixed a smaller wedge a

with a similar angle of 27°* The frame is now so placed that the edges of the wedges fall

1 F o r fuller description o f this instrument, see Appendix, p. 123. 2 See Appendix, p. 124.