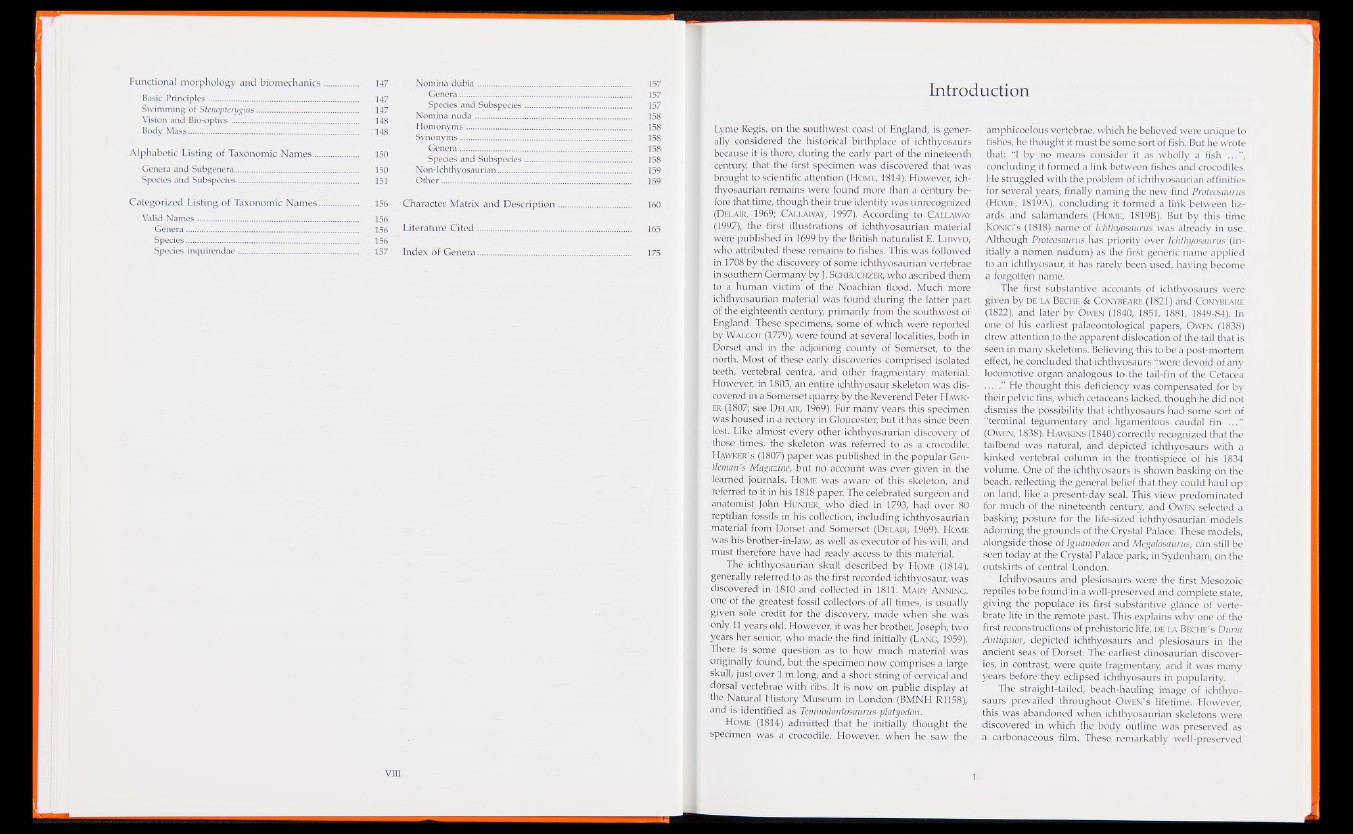

Functional morphology and biomechanics.............. 147

Basic Principles...................................... ...................... 147

Swimming of Stenopterygius.......................................... 147

Vision and Bio-optics..................................................... 148

Body Mass...................................................^.................. 148

Alphabetic Listing of Taxonomic Names.................. 150

Genera and Subgenera................................................... 150

Species and Subspecies.................................................. 151

Categorized Listing of Taxonomic Names................ 156

Valid Names................................................................... 156

Genera........................................................................ 156

Species................................................................. 156

Species inquirendae.................................................. 157

Nomina dubia................................................................ 157

Genera........................................................................ 157

Species and Subspecies............................................ 157

Nomina nuda................................................................. 158

Homonyms....................................................... 158

Synonyms........................................................................ 158

Genera........................................................................ 158

Species and Subspecies............................................ 158

Non-Ichthyosaurian........................................................ 159

Other............................................................................... 159

Character Matrix and Description................................ 160

Literature Cited................................................................ 165

Index of Genera................................................................ 175

Introduction

Lyme Regis, on the southwest coast of England, is generally

considered the historical birthplace of ichthyosaurs

because it is there, during the early part of the nineteenth

century, that the first specimen was discovered that was

brought to scientific attention (Home, 1814). However, ich-

thyosaurian remains were found more than a century before

that time, though their true identity was unrecognized

(Delair, 1969; Callaway, 1997). According to Callaway

(1997), the first illustrations of ichthyosaurian material

were published in 1699 by the British naturalist E. Lhwyd,

who attributed these remains to fishes. This was followed

in 1708 by the discovery of some ichthyosaurian vertebrae

in southern Germany by J. Scheuchzer, who ascribed them

to a human victim of the Noachian flood. Much more

ichthyosaurian material was found during the latter part

of the eighteenth century, primarily from the southwest of

England. These specimens, some of which were reported

by Walcot (1779), were found at several localities, both in

Dorset and in the adjoining county of Somerset, to the

north. Most of these early discoveries comprised isolated

teeth, vertebral centra, and other fragmentary material.

However, in 1803, an entire ichthyosaur skeleton was discovered

in a Somerset quarry by the Reverend Peter Hawker

(1807; see Delair, 1969). For many years this specimen

was housed in a rectory in Gloucester, but it has since been

lost. Like almost every other ichthyosaurian discovery of

those times, the skeleton was referred to as a crocodile.

Hawker’s (1807) paper was published in the popular Gentleman’s

Magazine, but no account was ever given in the

learned journals. H ome was aware of this skeleton, and

referred to it in his 1818 paper. The celebrated surgeon and

anatomist John Hunter, who died in 1793, had over 80

reptilian fossils in his collection, including ichthyosaurian

material from Dorset and Somerset (Delair, 1969). Home

was his brother-in-law, as well as executor of his will, and

must therefore have had ready access to this material.

The ichthyosaurian skull described by H ome (1814),

generally referred to as the first recorded ichthyosaur, was

discovered in 1810 and collected in 1811. Mary Anning,

one of the greatest fossil collectors of all times, is usually

given sole credit for the discovery, made when she was

only 11 years old. However, it was her brother, Joseph, two

years her senior, who made the find initially (Lang, 1959).

There is some question as to how much material was

originally found, but the specimen now comprises a large

skull, just over 1 m long, and a short string of cervical and

dorsal vertebrae with ribs. It is now on public display at

the Natural History Museum in London (BMNH R1158),

and is identified as Temnodontosaurus platyodon.

Home (1814) admitted that he initially thought the

specimen was a crocodile. However, when he saw the

amphicoelous vertebrae, which he believed were unique to

fishes, he thought it must be some sort of fish. But he wrote

that: “I by no means consider it as wholly a fish . . . ”

concluding it formed a link between fishes and crocodiles.

He struggled with the problem of ichthyosaurian affinities

for several years, finally naming the new find Proteosaurus

(Home, 1819A), concluding it formed a link between lizards

and salamanders (Home, 1819B). But by this time

KOnig’s (1818) name of Ichthyosaurus was already in use.

Although Proteosaurus has priority over Ichthyosaurus (initially

a nomen nudum) as the first generic name applied

to an ichthyosaur, it has rarely been used, having become

a forgotten name.

The first substantive accounts of ichthyosaurs were

given by de la Beche & Conybeare (1821) and Conybeare

(1822), and later by Owen (1840, 1851, 1881, 1849-84). In

one of his earliest palaeontological papers, Owen (1838)

drew attention to the apparent dislocation of the tail that is

seen in many skeletons. Believing this to be a post-mortem

effect, he concluded that ichthyosaurs “were devoid of any

locomotive organ analogous to the tail-fin of the Cetacea

... .” He thought this deficiency was compensated for by

their pelvic fins, which cetaceans lacked, though he did not

dismiss the possibility that ichthyosaurs had some sort of

“terminal tegumentary and ligamentous caudal fin . . . ”

(Owen, 1838). H awkins (1840) correctly recognized that the

tailbend was natural, and depicted ichthyosaurs with a

kinked vertebral column in the frontispiece of his 1834

volume. One of the ichthyosaurs is shown basking on the

beach, reflecting the general belief that they could haul up

on land, like a present-day seal. This view predominated

for much of the nineteenth century, and Owen selected a

basking posture for the life-sized ichthyosaurian models

adorning the grounds of the Crystal Palace. These models,

alongside those of Iguanodon and Megalosaurus, can still be

seen today at the Crystal Palace park, in Sydenham, on the

outskirts of central London.

Ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs were the first Mesozoic

reptiles to be found in a well-preserved and complete state,

giving the populace its first substantive glance of vertebrate

life in the remote past. This explains why one of the

first reconstructions of prehistoric life, de la Beche’s Duria

Antiquior, depicted ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs in the

ancient seas of Dorset. The earliest dinosaurian discoveries,

in contrast, were quite fragmentary, and it was many

years before they eclipsed ichthyosaurs in popularity.

The straight-tailed, beach-hauling image of ichthyosaurs

prevailed throughout Owen’s lifetime. However,

this was abandoned when ichthyosaurian skeletons were

discovered in which the body outline was preserved as

a carbonaceous film. These remarkably well-preserved