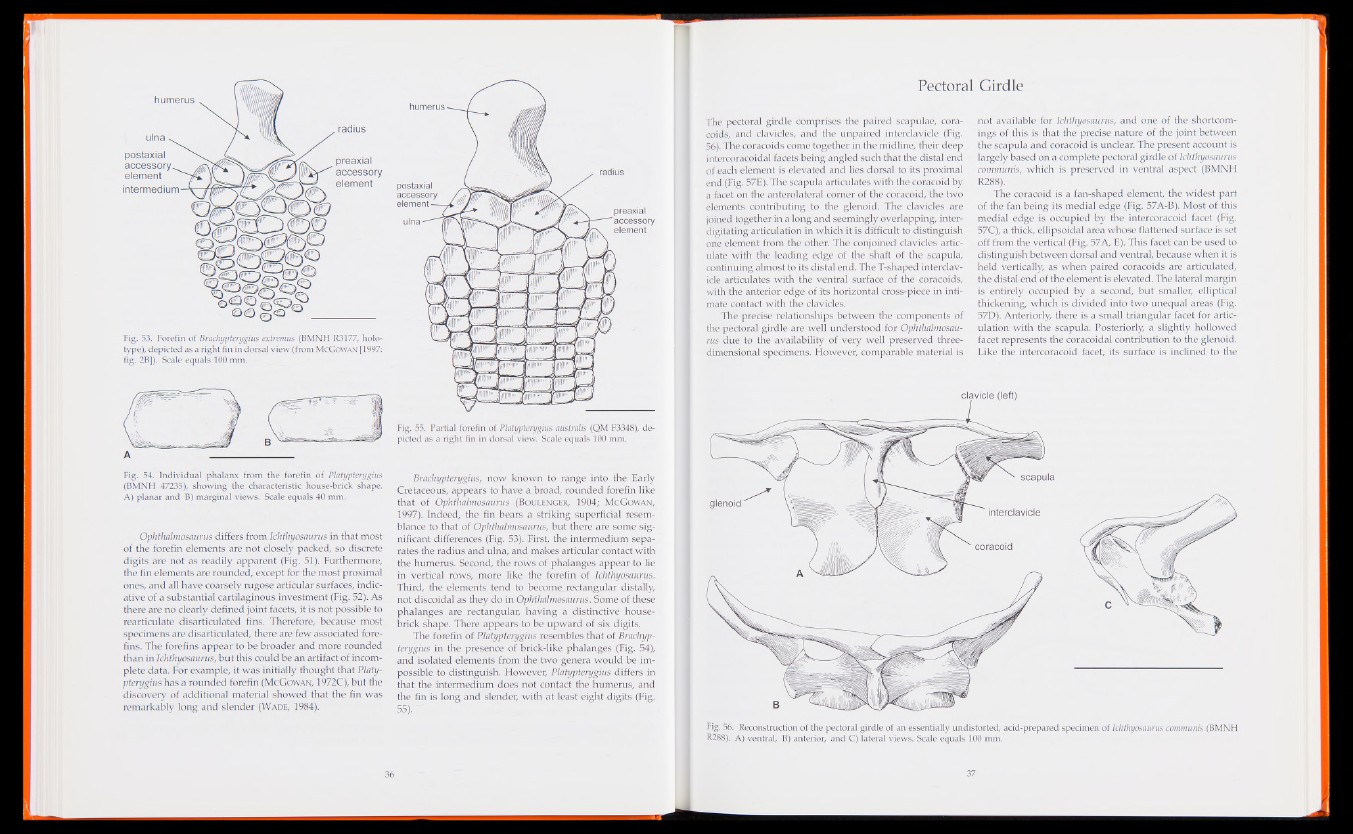

Fig. 53. Forefin of Brachypterygius extremus (BMNH R3177, holo-

type), depicted as a right fin in dorsal view (from McGowan [1997:

fig. 2B]). Scale equals 100 mm.

A

Fig. 54. Individual phalanx from the forefin of Platypterygius

(BMNH 47235), showing the characteristic house-brick shape.

A) planar and B) marginal views. Scale equals 40 mm.

Ophthalmosaurus differs from Ichthyosaurus in that most

of the forefin elements are not closely packed, so discrete

digits are not as readily apparent (Fig. 51). Furthermore,

the fin elements are rounded, except for the most proximal

ones, and all have coarsely rugose articular surfaces, indicative

of a substantial cartilaginous investment (Fig. 52). As

there are no clearly defined joint facets, it is not possible to

rearticulate disarticulated fins. Therefore, because most

specimens are disarticulated, there are few associated fore-

fins. The forefins appear to be broader and more rounded

than in Ichthyosaurus, but this could be an artifact of incomplete

data. For example, it was initially thought that Platypterygius

has a rounded forefin (McGowan, 1972C), but the

discovery of additional material showed that the fin was

remarkably long and slender (Wade, 1984).

Fig. 55. Partial forefin of Platypterygius australis (QM F3348), depicted

as a right fin in dorsal view. Scale equals 100 mm.

Brachypterygius, now known to range into the Early

Cretaceous, appears to have a broad, rounded forefin like

that of Ophthalmosaurus (Boulenger, 1904; McGowan,

1997). Indeed,-the fin bears a striking superficial resemblance

to that of Ophthalmosaurus, but there are some significant

differences (Fig. 53). First, the intermedium separates

the radius and ulna, and makes articular contact with

the humerus. Second, the rows of phalanges appear to lie

in vertical rows, more like the forefin of Ichthyosaurus.

Third, the elements tend to become_ rectangular distally,

not discoidal as they do in Ophthalmosaurus. Some of these

phalanges are rectangular, having a distinctive house-

brick shape. There appears to be upward of six digits.

The forefin of Platypterygius resembles that of Brachypterygius

in the presence of brick-like phalanges (Fig. 54),

and isolated elements from the two genera would be impossible

to distinguish. However, Platypterygius differs in

that the intermedium does not contact the humerus, and

the fin is long and slender, with at least eight digits (Fig.

55).

Pectoral Girdle

The pectoral girdle comprises the paired scapulae, coracoids,

and clavicles, and the unpaired interclavicle (Fig.

56). The coracoids come together in the midline, their deep

intercoracoidal facets being angled such that the distal end

of each element is elevated and lies dorsal to its proximal

end (Fig. 57E). The scapula articulates with the coracoid by

a facet on the anterolateral comer of the coracoid, the two

elements contributing to the glenoid. The clavicles are

joined together in a long and seemingly overlapping, inter-

digitating articulation in which it is difficult to distinguish

one element from the other. The conjoined clavicles articulate

with the leading edge of the shaft of the scapula,

continuing almost to its distal end. The T-shaped interclavicle

articulates with the ventral surface of the coracoids,

with the anterior edge of its horizontal cross-piece in intimate

contact with the clavicles.

The precise relationships between the components of

the pectoral girdle are well understood for Ophthalmosaurus

due to the availability of very well preserved three-

dimensional specimens. However, comparable material is

not available for Ichthyosaurus, and one of the shortcomings

of this is that the precise nature of the joint between

the scapula and coracoid is unclear. The present account is

largely based on a complete pectoral girdle of Ichthyosaurus

communis, which is preserved in ventral aspect (BMNH

R288).

The coracoid is a fan-shaped element, the widest part

of the fan being its medial edge (Fig. 57A-B). Most of this

medial edge is occupied by the intercoracoid facet (Fig.

57C), a thick, ellipsoidal area whose flattened surface is set

off from the vertical (Fig. 57A, E). This facet can be used to

distinguish between dorsal and ventral, because when it is

held vertically, as when paired coracoids are articulated,

the distal end of the element is elevated. The lateral margin

is entirely occupied by a second, but smaller, elliptical

thickening, which is divided into two unequal areas (Fig.

57D). Anteriorly, there is a small triangular facet for articulation

with the scapula. Posteriorly, a slightly hollowed

facet represents the coracoidal contribution to the glenoid.

Like the intercoracoid facet, its surface is inclined to the

Fig. 56. Reconstruction of the pectoral girdle of an essentially undistorted, acid-prepared specimen of Ichthyosaurus communis (BMNH

R288). A) ventral, B) anterior, and C) lateral views. Scale equals 100 mm.