with stout roots. Ribs thick and stout. Vertebrae massive.

Pelvic girdle as wide as pectoral girdle; large ischium fused

with pubis, but at proximal end only. Tetradigitate hind-

limb, % length of forefin; femur with two distal facets;

phalanges rounded.

Remarks: The forefin looks very much like that of Yasykovia

Efimov, 1999A, which is probably a subjective junior

synonym for Ophthalmosaurus. This raises the possibility

that this genus might also be synonymous. Maisch &

Matzke (2000B) synonymized Undorosaurus with Ophthalmosaurus,

but the two differ in significant regards: the

pubis and ischium are not completely fused, and the teeth

are large. Therefore, it appears that Undorosaurus is distinct

from Ophthalmosaurus, but the two appear to have close

affinities.

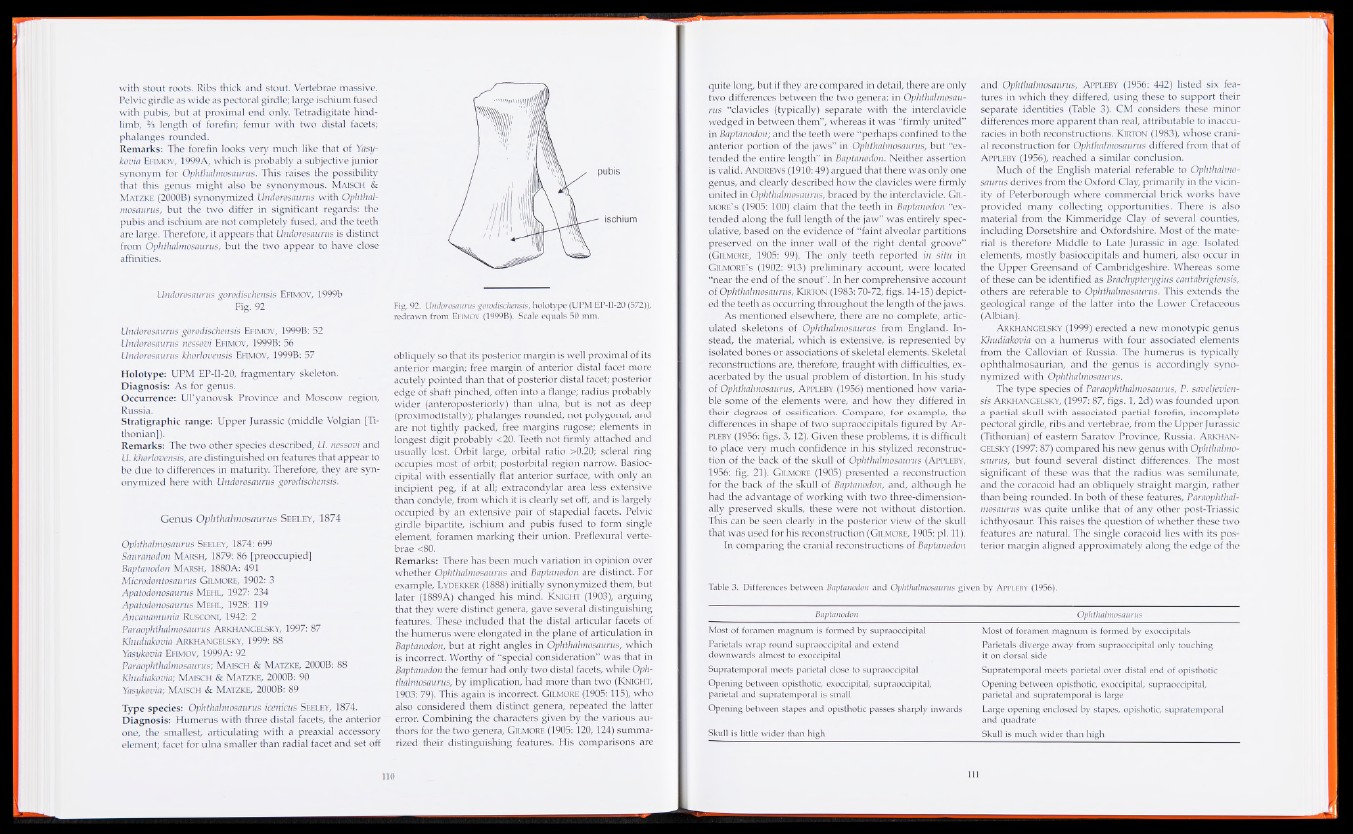

Undorosaurus gorodischensis Efimov, 1999b

Fig. 92

Undorosaurus gorodischensis Efimov, 1999B: 52

Undorosaurus nessovi Efimov, 1999B: 56

Undorosaurus khorlovensis Efimov, 1999B: 57

Holotype: UPM EP-II-20, fragmentary skeleton.

Diagnosis: As for genus.

Occurrence: Ul’yanovsk Province and Moscow region,

Russia.

Stratigraphic range: Upper Jurassic (middle Volgian [Ti-

thonian]).

Remarks: The two other species described, U. nessovi and

U. khorlovensis, are distinguished on features that appear to

be due to differences in maturity. Therefore, they are synonymized

here with Undorosaurus gorodischensis.

Genus Ophthalmosaurus Se e l e y , 1874

Ophthalmosaurus Seeley, 1874: 699

Sauranodon Marsh, 1879: 86 [preoccupied]

Baptanodon Marsh, 1880A: 491

Microdontosaurus Gilmore, 1902: 3

Apatodonosaurus Mehl, 1927: 234

Apatodonosaurus Mehl, 1928: 119

Ancanamunia Rusconi, 1942: 2

Paraophthalmosaurus A rkhangelsky, 1997: 87

Khudiakovia Arkhangelsky, 1999: 88

Yasykovia E fimov, 1999A: 92

Paraophthalmosaurus; Maisch & Matzke, 2000B: 88

Khudiakovia; Maisch & Matzke, 2000B: 90

Yasykovia; Maisch & Matzke, 2000B: 89

Type species: Ophthalmosaurus icenicus Seeley, 1874.

Diagnosis: Humerus with three distal facets, the anterior

one, the smallest, articulating with a preaxial accessory

element; facet for ulna smaller than radial facet and set off

Fig. 92. Undorosaurus gorodischensis, holotype (UPM EP-II-20 (572)),

redrawn from Ef im o v (1999B). Scale equals 50 mm.

obliquely so that its posterior margin is well proximal of its

anterior margin; free margin of anterior distal facet more

acutely pointed than that of posterior distal facet; posterior

edge of shaft pinched, often into a flange; radius probably

wider (anteroposteriorly) than ulna, but is not as deep

(proximodistally); phalanges rounded, not polygonal, and

are not tightly packed, free margins rugose; elements in

longest digit probably <20. Teeth not firmly attached and

usually lost. Orbit large, orbital ratio >0.20; scleral ring

occupies most of orbit; postorbital region narrow. Basioc-

cipital with essentially flat anterior surface, with only an

incipient peg, if at all; extracondylar area less extensive

than condyle, from which it is clearly set off, and is largely

occupied by an extensive pair of stapedial facets. Pelvic

girdle bipartite, ischium and pubis fused to form single

element, foramen marking their union. Preflexural vertebrae

<80.

Remarks: There has been much variation in opinion over

whether Ophthalmosaurus and Baptanodon are distinct. For

example, Lydekker (1888) initially synonymized them, but

later (1889A) changed his mind. Knight (1903), arguing

that they were distinct genera, gave several distinguishing

features. These included that the distal articular facets of

the humerus were elongated in the plane of articulation in

Baptanodon, but at right angles in Ophthalmosaurus, which

is incorrect. Worthy of “special consideration” was that in

Baptanodon the femur had only two distal facets, while Ophthalmosaurus,

by implication, had more than two (Knight,

1903: 79). This again is incorrect. Gilmore (1905:115), who

also considered them distinct genera, repeated the latter

error. Combining the characters given by the various authors

for the two genera, Gilmore (1905:120,124) summarized

their distinguishing features. His comparisons are

quite long, but if they are compared in detail, there are only

two differences between the two genera: in Ophthalmosaurus

“clavicles (typically) separate with the interclavicle

wedged in between them”, whereas it was “firmly united”

in Baptanodon; and the teeth were “perhaps confined to the

anterior portion of the jaws” in Ophthalmosaurus, but “extended

the entire length” in Baptanodon. Neither assertion

is valid. A ndrews (1 9 1 0 :4 9 ) argued that there was only one

genus, and clearly described how the clavicles were firmly

united in Ophthalmosaurus, braced by the interclavicle. Gilmore’s

(1905: 100) claim that the teeth in Baptanodon “extended

along the full length of the jaw” was entirely speculative,

based on the evidence of “faint alveolar partitions

preserved on the inner wall of the right dental groove”

(Gilmore, 1905: 99). The only teeth reported in situ in

Gilmore’s (1902: 9 13) preliminary account, were located

“near the end of the snout”. In her comprehensive account

of Ophthalmosaurus, Kirton (1 9 8 3 :7 0 -7 2 , figs. 14-15) depicted

the teeth as occurring throughout the length of the jaws.

As mentioned elsewhere, there are no complete, articulated

skeletons of Ophthalmosaurus from England. Instead,

the material, which is extensive, is represented by

isolated bones or associations of skeletal elements. Skeletal

reconstructions are, therefore, fraught with difficulties, exacerbated

by the usual problem of distortion. In his study

of Ophthalmosaurus, A ppleby (1956) mentioned how variable

some of the elements were, and how they differed in

their degrees of ossification. Compare, for example, the

differences in shape of two supraoccipitals figured by A ppleby

(1956: figs. 3 ,1 2 ) . Given these problems, it is difficult

to place very much confidence in his stylized reconstruction

of the back o f the skull of Ophthalmosaurus (Appleby,

1956: fig. 21). Gilmore (1905) presented a reconstruction

for the back of the skull of Baptanodon, and, although he

had the advantage of working with two three-dimension-

ally preserved skulls, these were not without distortion.

This can be seen clearly in the posterior view of the skull

that was used for his reconstruction (Gilmore, 1905: pi. 11).

In comparing the cranial reconstructions of Baptanodon

and Ophthalmosaurus, Appleby (1956: 44 2 ) listed six features

in which they differed, using these to support their

separate identities (Table 3). CM considers these minor

differences more apparent than real, attributable to inaccuracies

in both reconstructions. Kirton (1983), whose cranial

reconstruction for Ophthalmosaurus differed from that of

A ppleby (1956), reached a similar conclusion.

Much of the English material referable to Ophthalmosaurus

derives from the Oxford Clay, primarily in the vicinity

of Peterborough where commercial brick works have

provided many collecting opportunities. There is also

material from the Kimmeridge Clay of several counties,

including Dorsetshire and Oxfordshire. Most of the material

is therefore Middle to Late Jurassic in age. Isolated

elements, mostly basioccipitals and humeri, also occur in

the Upper Greensand of Cambridgeshire. Whereas some

of these can be identified as Brachypterygius cantabrigiensis,

others are referable to Ophthalmosaurus. This extends the

geological range of the latter into the Lower Cretaceous

(Albian).

Arkhangelsky (1999) erected a new monotypic genus

Khudiakovia on a humerus with four associated elements

from the Callovian of Russia. The humerus is typically

ophthalmosaurian, and the genus is accordingly synonymized

with Ophthalmosaurus.

The type species of Paraophthalmosaurus, P. saveljevien-

sis Arkhangelsky, (1997: 87, figs. 1, 2d) was founded upon

a partial skull with associated partial forefin, incomplete

pectoral girdle, ribs and vertebrae, from the Upper Jurassic

(Tithonian) of eastern Saratov Province, Russia. A rkhangelsky

(1997:87) compared his new genus with Ophthalmosaurus,

but found several distinct differences. The most

significant of these was that the radius was semilunate,

and the coracoid had an obliquely straight margin, rather

than being rounded. In both of these features, Paraophthalmosaurus

was quite unlike that of any other post-Triassic

ichthyosaur. This raises the question of whether these two

features are natural. The single coracoid lies with its posterior

margin aligned approximately along the edge of the

Table 3. Differences between Baptanodon and Ophthalmosaurus given by A ppleby (1956).

Baptanodon

Most of foramen magnum is formed by supraoccipital

Parietals wrap round supraoccipital and extend

downwards almost to exoccipital

Supratemporal meets parietal close to supraoccipital

Opening between opisthotic, exoccipital, supraoccipital,

parietal and supratemporal is small

Opening between stapes and opisthotic passes sharply inwards

Skull is little wider than high

Ophthalmosaurus

Most of foramen magnum is formed by exoccipitals

Parietals diverge away from supraoccipital only touching

it on dorsal side

Supratemporal meets parietal over distal end of opisthotic

Opening between opisthotic, exoccipital, supraoccipital,

parietal and supratemporal is large

Large opening enclosed by stapes, opishotic, supratemporal

and quadrate

Skull is much wider than high