teeth, including those few specimens which have been

preserved with the jaws agape. This is presumably because

the teeth are so firmly attached.

As seen in serial sections, the dental groove does not

extend the entire depth of the snout or mandible (Fig. 42).

Instead, it is delimited by an essentially horizontal shelf,

extending from the premaxilla, or from the dentary, against

which the base of the teeth abut. The teeth typically have

much of the root exposed, giving the impression that some

displacement from the groove has occurred. However, this

is unlikely, as revealed by a three-dimensional rostral segment

from a large skull that is probably referable to Temn-

odontosaurus platyodon (Fig. 45). Several of the teeth are

exposed in their entirety, and their roots extend well beyond

the distal edge of the dental groove. However, the

proximal ends of the roots are in contact with the horizontal

shelf, showing that they have not been displaced.

Hyoid

The hyoid apparatus, which is seldom exposed, appears to

comprise a pair of stout rods that lie medial to the mandibular

rami, at about the level of the orbits (Fig. 43). Sollas

(1916: fig. 15) described and figured a fairly complex apparatus,

which he admitted did not resemble that of any

extant reptile. KlRTON (1983) believed the reason for this

seeming complexity is that some displaced ribs were associated

with the hyoid apparatus in Sollas’s specimen. This

seems more than likely, and can also be seen elsewhere.

Thus, in BMNH 49203 (I. communis), a rod-like element lies

in contact with the right ramus of the hyoid (not shown in

Fig. 43), and this could be interpreted as part of the apparatus.

However, one end of this bone has a shallow furrow,

with a slightly raised edge, which is identified as a displaced

rib. The hyoid is exposed on one side in BMNH

R1158, a mature specimen of T. platyodon, and is exactly

similar to that of I communis.

Forefin

Humerus

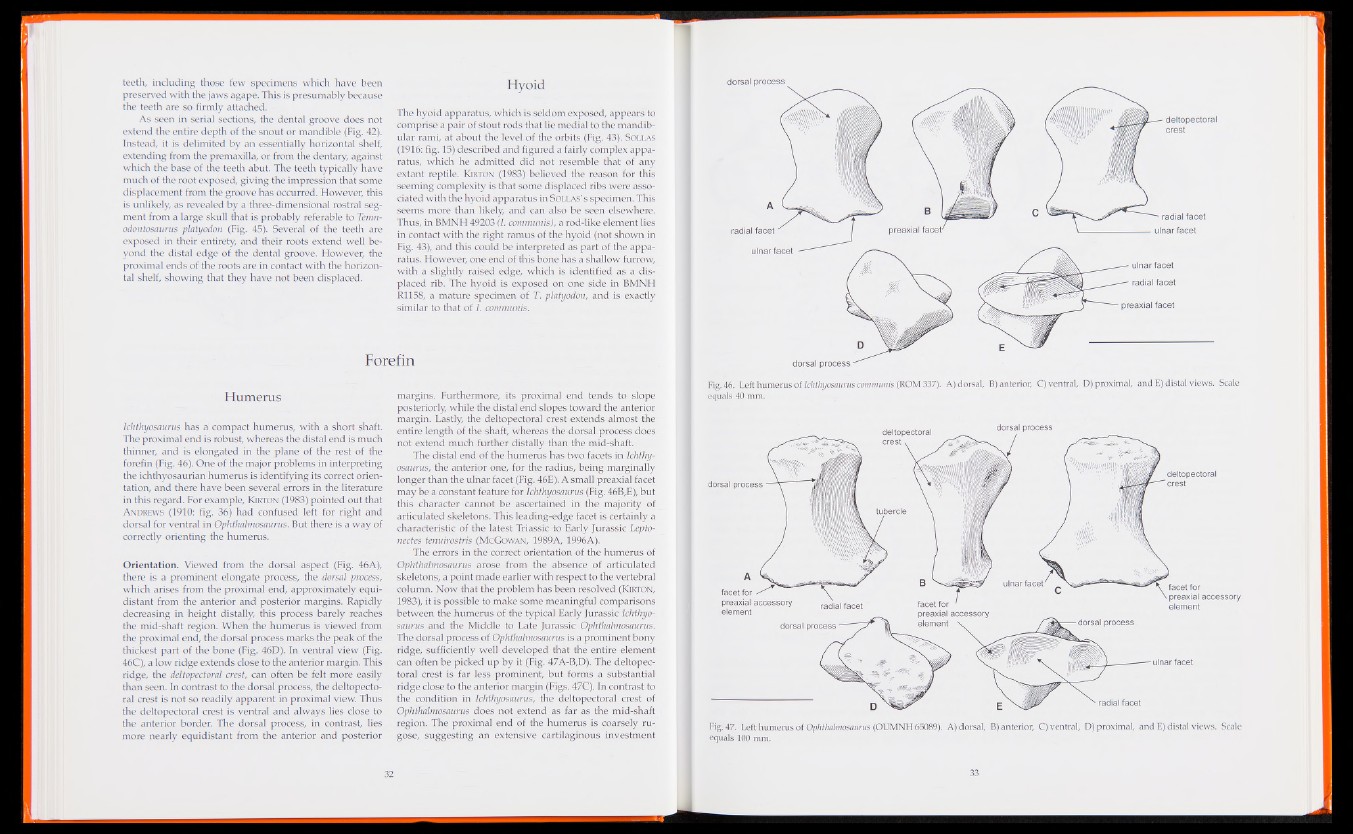

Ichthyosaurus has a compact humerus, with a short shaft.

The proximal end is robust, whereas the distal end is much

thinner, and is elongated in the plane of the rest of the

forefin (Fig. 46). One of the major problems in interpreting

the ichthyosaurian humerus is identifying its correct orientation,

and there have been several errors in the literature

in this regard. For example, Kjrton (1983) pointed out that

Andrews (1910: fig. 36) had confused left for right and

dorsal for ventral in Ophthalmosaurus. But there is a way of

correctly orienting the humerus.

Orientation. Viewed from the dorsal aspect (Fig. 46A),

there is a prominent elongate process, the dorsal process,

which arises from the proximal end, approximately equidistant

from the anterior and posterior margins. Rapidly

decreasing in height distally, this process barely reaches

the mid-shaft region. When the humerus is viewed from

the proximal end, the dorsal process marks the peak of the

thickest part of the bone (Fig. 46D). In ventral view (Fig.

46C), a low ridge extends close to the anterior margin. This

ridge, the deltopectoral crest, can often be felt more easily

than seen. In contrast to the dorsal process, the deltopectoral

crest is not so readily apparent in proximal view. Thus

the deltopectoral crest is ventral and always lies close to

the anterior border. The dorsal process, in contrast, lies

more nearly equidistant from the anterior and posterior

margins. Furthermore, its proximal end tends to slope

posteriorly, while the distal end slopes toward the anterior

margin. Lastly, the deltopectoral crest extends almost the

entire length of the shaft, whereas the dorsal process does

not extend much further distally than the mid-shaft.

The distal end of the humerus has two facets in Ichthyosaurus,

the anterior one, for the radius, being marginally

longer than the ulnar facet (Fig. 46E). A small preaxial facet

may be a constant feature for Ichthyosaurus (Fig. 46B,E), but

this character cannot be ascertained in the majority of

articulated skeletons. This leading-edge facet is certainly a

characteristic of the latest Triassic to Early Jurassic Lepto-

nectes tenuirostris (McGowan, 1989A, 1996A).

The errors in the correct orientation of the humerus of

Ophthalmosaurus arose from the absence of articulated

skeletons, a point made earlier with respect to the vertebral

column. Now that the problem has been resolved (Kirton,

1983), it is possible to make some meaningful comparisons

between the humerus of the typical Early Jurassic Ichthyosaurus

and the Middle to Late Jurassic Ophthalmosaurus.

The dorsal process of Ophthalmosaurus is a prominent bony

ridge, sufficiently well developed that the entire element

can often be picked up by it (Fig. 47A-B,D). The deltopectoral

crest is far less prominent, but forms a substantial

ridge close to the anterior margin (Figs. 47C). In contrast to

the condition in Ichthyosaurus, the deltopectoral crest of

Ophthalmosaurus does not extend as far as the mid-shaft

region. The proximal end of the humerus is coarsely rugose,

suggesting an extensive cartilaginous investment

dorsal process

deltopectoral

crest

—■ radial facet

radial facet preaxial facet' ulnar facet

ulnar facet

radial facet

preaxial facet

dorsal process -—

Fig. 46. Left humerus of Ichthyosaurus communis (ROM 337). A) dorsal, B) anterior, C) ventral, D) proximal, and E) distal views. Scale

equals 40 mm.

deltopectoral dorsal process

crest v

deltopectoral

dorsal process crest

tubercle

ulnar facet' facet for

preaxial accessory

element

facet for / ^

preaxial accessory

element

facet for '

preaxial accessory

element v

radial facet

dorsal process dorsal process

ulnar facet

radial facet

Fig. 47. Left humerus of Ophthalmosaurus (OUMNH 65089). A) dorsal, B) anterior, C) ventral, D) proximal, and E) distal views. Scale

equals 100 mm.