lachrymal

parietal

supratemporal

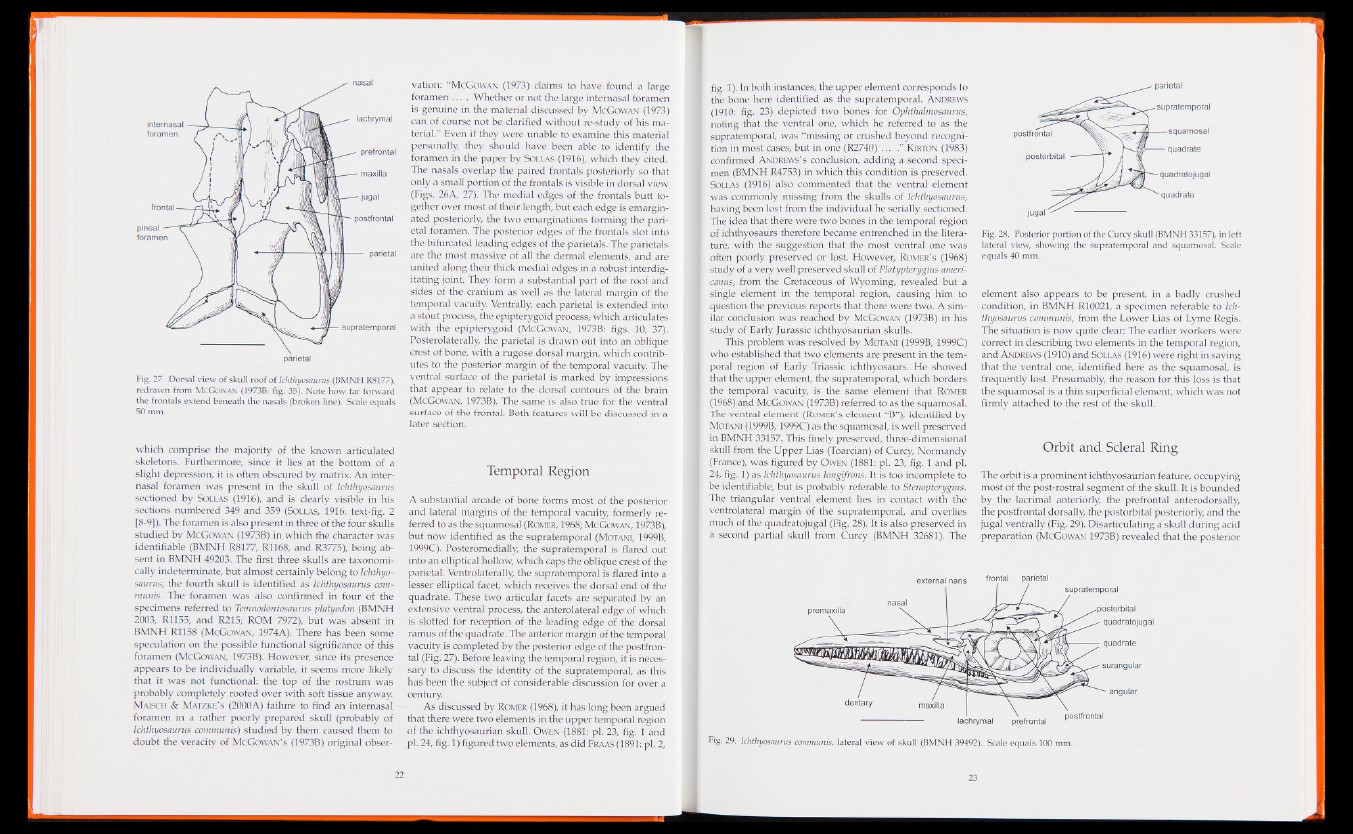

Fig. 27. Dorsal view of skull roof of Ichthyosaurus (BMNH R8177),

redrawn from McGowan (1973B: fig. 35). Note how far forward

the frontals extend beneath the nasals (broken line). Scale equals

50 mm.

vation: “McGowan (1973) claims to have found a large

foramen . . . . Whether or not the large intemasal foramen

is genuine in the material discussed by McGowan (1973)

can of course not be clarified without re-study of his material.”

Even if they were unable to examine this material

personally they should have been able to identify the

foramen in the paper by Sollas (1916), which they cited.

The nasals overlap the paired frontals posteriorly so that

only a small portion of the frontals is visible in dorsal view

(Figs. 26A, 27). The medial edges of the frontals butt together

over most of their length, but each edge is emargin-

ated posteriorly, the two emarginations forming the parietal

foramen. The posterior edges of the frontals slot into

the bifurcated leading edges of the parietals. The parietals

are the most massive of all the dermal elements, and are

united along their thick medial edges in a robust interdig-

itating joint. They form a substantial part of the roof and

sides of the cranium as well as the lateral margin of the

temporal vacuity. Ventrally, each parietal is extended into

a stout process, the epipterygoid process, which articulates

with the epipterygoid (McGowan, 1973B: figs. 10, 37).

Posterolaterally, the parietal is drawn out into an oblique

crest of bone, with a rugose dorsal margin, which contributes

to the posterior margin of the temporal vacuity. The

ventral surface of the parietal is marked by impressions

that appear to relate to the dorsal contours of the brain

(McGowan, 1973B). The same is also true for the ventral

surface of the frontal. Both features will be discussed in a

later section.

which comprise the majority of the known articulated

skeletons. Furthermore, since it lies at the bottom of a

slight depression, it is often obscured by matrix. An internasal

foramen was present in the skull of Ichthyosaurus

sectioned by Sollas (1916), and is clearly visible in his

sections numbered 349 and 359 (Sollas, 1916: text-fig. 2

[8-9]). The foramen is also present in three of the four skulls

studied by McGowan (1973B) in which the character was

identifiable (BMNH R8177, R1168, and R3775), being absent

in BMNH 49203. The first three skulls are taxonomi-

cally indeterminate, but almost certainly belong to Ichthyosaurus;

the fourth skull is identified as Ichthyosaurus communis.

The foramen was also confirmed in four of the

specimens referred to Temnodontosaurus platyodon (BMNH

2003, R1155, and R215; ROM 7972), but was absent in

BMNH R1158 (McGowan, 1974A). There has been some

speculation on the possible functional significance of this

foramen (McGowan, 1973B). However, since its presence

appears to be individually variable, it seems more likely

that it was not functional: the top of the rostrum was

probably completely roofed over with soft tissue anyway.

Maisch & Matzke’s (2000A) failure to find an internasal

foramen in a rather poorly prepared skull (probably of

Ichthyosaurus communis) studied by them caused them to

doubt the veracity of McGowan’s (1973B) original obser-

Temporal Region

A substantial arcade of bone forms most of the posterior

and lateral margins of the temporal vacuity, formerly referred

to as the squamosal (RomER, 1968; McGowan, 1973B),

but now identified as the supratemporal (Motani, 1999B,

1999C). Posteromedially, the supratemporal is flared out

into an elliptical hollow, which caps the oblique crest of the

parietal. Ventrolaterally, the supratemporal is flared into a

lesser elliptical facet, which receives the dorsal end of the

quadrate. These two articular facets are separated by an

extensive ventral process, the anterolateral edge of which

is slotted for reception of the leading edge of the dorsal

ramus of the quadrate. The anterior margin of the temporal

vacuity is completed by the posterior edge of the postfrontal

(Fig. 27). Before leaving the temporal region, it is necessary

to discuss the identity of the supratemporal, as this

has been the subject of considerable discussion for over a

century.

As discussed by Romer (1968), it has long been argued

that there were two elements in the upper temporal region

of the ichthyosaurian skull. Owen (1881: pi. 23, fig. 1 and

pi. 24, fig. 1) figured two elements, as did Fraas (1891: pi. 2,

fig. 1). In both instances, the upper element corresponds to

the bone here identified as the supratemporal. Andrews

(1910: fig. 23) depicted two bones for Ophthalmosaurus,

noting that the ventral one, which he referred to as the

supratemporal, was “missing or crushed beyond recognition

in most cases, but in one (R2740) ... .” Kirton (1983)

confirmed Andrews’s conclusion, adding a second specimen

(BMNH R4753) in which this condition is preserved.

Sollas (1916) also commented that the ventral element

was commonly missing from the skulls of Ichthyosaurus,

having been lost from the individual he serially sectioned.

The idea that there were two bones in the temporal region

of ichthyosaurs therefore became entrenched in the literature,

with the suggestion that the most ventral one was

often poorly preserved or lost. However, Romer’s (1968)

study of a very well preserved skull of Platypterygius ameri-

canus, from the Cretaceous of Wyoming, revealed but a

single element in the temporal region, causing him to

question the previous reports that there were two. A similar

conclusion was reached by McGowan (1973B) in his

study of Early Jurassic ichthyosaurian skulls.

This problem was resolved by Motani (1999B, 1999C)

who established that two elements are present in the temporal

region of Early Triassic ichthyosaurs. He showed

that the upper element, the supratemporal, which borders

the temporal vacuity, is the same element that Romer

(1968) and McGowan (1973B) referred to as the squamosal.

The ventral element (Romer’s element “B”), identified by

Motani (1999B, 1999C) as the squamosal, is well preserved

in BMNH 33157. This finely preserved, three-dimensional

skull from the Upper Lias (Toarcian) of Curcy, Normandy

(France), was figured by Owen (1881: pi. 23, fig. 1 and pi.

24, fig. 1) as Ichthyosaurus longifrons. It is too incomplete to

be identifiable, but is probably referable to Stenopterygius.

The triangular ventral element lies in contact with the

ventrolateral margin of the supratemporal, and overlies

much of the quadratojugal (Fig. 28). It is also preserved in

a second partial skull from Curcy (BMNH 32681). The

Fig. 28. Posterior portion of the Curcy skull (BMNH 33157), in left

lateral view, showing the supratemporal and squamosal. Scale

equals 40 mm.

element also appears to be present, in a badly crushed

condition, in BMNH R10021, a specimen referable to Ichthyosaurus

communis, from the Lower Lias of Lyme Regis.

The situation is now quite clear: The earlier workers were

correct in describing two elements in the temporal region,

and Andrews (1910) and Sollas (1916) were right in saying

that the ventral one, identified here as the squamosal, is

frequently lost. Presumably, the reason for this loss is that

the squamosal is a thin superficial element, which was not

firmly attached to the rest of the skull.

Orbit and Scleral Ring

The orbit is a prominent ichthyosaurian feature, occupying

most of the post-rostral segment of the skull. It is bounded

by the lacrimal anteriorly, the prefrontal anterodorsally,

the postfrontal dorsally, the postorbital posteriorly, and the

jugal ventrally (Fig. 29). Disarticulating a skull during acid

preparation (McGowan 1973B) revealed that the posterior

Fig. 29. Ichthyosaurus communis, lateral view of skull (BMNH 39492). Scale equals 100 mm.