Such a high ratio is again characteristic of this body plan.

The limbs were fin-shaped, with zeugopodials retaining a

shaft but not as elongated as in the basal plan. The carpals

are rectangular or squarish, being tightly packed, but are

distinct from the metacarpals and phalanges that retain

shafts.

45 (±5) presacral vertebrae. The trunk vertebral centra are

discoidal, with height/length ratios of about 2.5 near the

pelvic girdle. There is some increase of centra height posterior

to the caudal peak (i.e., tailbend), although not as

extensively as in the mixosaurian plan. The metacarpals

and phalanges lack shafts, and the carpals are closely

packed.

Parvipelvian plan

(Fig. 68F-G)

The parvipelvian plan is known from numerous complete

skeletons, and is the best known of the four body plans.

Most characteristically, the pelvic girdle is remarkably reduced

anteroposteriorly. The caudal peak has been modified

to form a tailbend, supporting a lunate caudal fin. A

dorsal fin is present at least in some forms. There are about

Californosaurus

(Fig. 68E)

This genus probably represents a body plan that is basal to

the parvipelvian plan. The presacral count is about 45 and

there appears to be a tailbend, but the pelvic girdle is still

moderately large.

Review of Body Part Evolution

Skull

(Fig. 69)

The cranial bones in ichthyopterygians overlap one another

extensively. This sometimes leads to misinterpretation

of sutural lines, because apparent sutures move when the

surface bone breaks off, exposing the underlying element.

Also, variation in bone growth among and within individuals

could move the suture extensively for similar reasons.

In addition, certain elements, such as the jugal, may be

partially disarticulated, and this could lead to misinterpretation

of suture lines. Therefore, attention should be paid

to preservational factors as well as individual and ontogenetic

variation when interpreting ichthyopterygian skulls,

and whether or not one bone misses contact with another

by a small amount should not be taken seriously in phylogenetic

discussions.

The skulls of all ichthyosaurs share a single basic plan.

The snout is narrow and elongated, with the external nares

located proximally rather than at its rostral tip. The orbit is

large, with a narrow, rod-like jugal forming its ventral

margin. The scleral ring is also large (but not always preserved).

There is a pair of supratemporal fenestrae, but no

definitive infratemporal fenestrae. A pineal foramen is always

present. Ichthyopterygian cranial structure diversified

within this basic framework.

The pineal foramen is enclosed between the anterior

processes of the parietals in basal forms, at least in dorsal

view. It is possible that the frontals made a contribution to

the foramen on the ventral aspect of the skull roof. The

anterior parietal processes became reduced in the stem

plan to form a parietal fork (Motani, 1999C), and thus the

pineal foramen was located on the suture of the parietal

and frontal, being enclosed within the fork. The regression

of the parietal along the medial line further proceeded in

the Parvipelvia, where the pineal foramen is sometimes

entirely enclosed between the frontals.

The parietal also went through a remarkable modification

posteriorly. In basal forms and Cymbospondylus, the

posterolateral (supratemporal) process of the parietal was

long and narrow, and the parietal ridge, a structure unique

to derived ichthyosaurs, was absent. This latter structure

appeared in Mixosaurus and persisted in parvipelvians,

although its presence has yet to be confirmed for shasta-

saurines. The supratemporal process was shortened to

various degrees in these forms.

Another important feature of the skull roof is the anterior

terrace of the supratemporal fenestra, which is the

depressed area of the skull roof along the anterior margin

of the supratemporal fenestra. The terrace appears as if it

were sculpted on the skull roof, with its anterior limit

clearly marked by a parabolic line. The presence of this

structure is plesiomorphic for ichthyopterygians. Sutural

lines are difficult to follow on the terrace, but it appears

that three bones, namely the parietal, frontal, and postfrontal,

were involved in the formation of this structure in basal

ichthyosaurs (Motani et al., 1998; Motani, 2000A). The

terrace became smaller in the stem ichthyosaurs, as the

frontal became eliminated from the area. Most parvipelvians

lost this structure, but at least one specimen of Lepto-

nectes (ROM 30127) and another of an undescribed new

species from the Lower Lias (BMNH R3000) retained it.

The terrace is clearly defined only on the postfrontal in

these specimens, but it should also be considered that the

postfrontal is remarkably enlarged in parvipelvians compared

to the more basal forms. A reverse trend is seen in

mixosaurians: the terrace was remarkably expanded in

these forms, almost reaching the external naris anteriorly,

and this large terrace is one of the synapomorphies for the

Mixosauria (Motani, 1999B, 1999C). The functional significance

of these enlarged terraces is unclear. One possibility

is that they accommodated salt glands in the expanded

anterior region; the area corresponds to the position of salt

glands in extant marine iguanas (Dunson, 1976).

The basic configuration of the cheek region remained

unchanged, although there were variations in the relative

extent of areas occupied by the bones involved (viz., the

supratemporal, squamosal, quadratojugal, jugal, postorbital,

and postfrontal). These six elements were almost

always present, except for the squamosal that has been

reported to be absent in Ichthyosaurus (McGowah 1973B)

and Platypterygius (Romer, 1968) (see discussion above).

The contact between the jugal and quadratojugal was absent

in basal ichthyosaurs, but present in derived forms.

Plesiomorphically, the postfrontal had a posterior process

that overlapped the postorbital, but the process became

reduced and eventually disappeared in derived forms.

The external nares were located close to the sagittal

plane in basal ichthyopterygians, with a narrow bar formed

by the nasal and premaxilla separating the paired openings.

They faced dorsolaterally in these forms, suggesting

that the animals may have been able to breathe while

largely submerged in the water. In the stem, mixosaurian,

and parvipelvian skulls, the nasal in the narial area is much

thickened and elevated, displacing the nares toward both

sides of the skull. These laterally facing nares would have

required the animals to emerge a large part of their heads

to break the water surface to breathe.

Dentition

The tooth crowns are mostly conical, but there are variations

and exceptions. Rounded crowns are known in the

posterior part of the jaw in Chaohusaurus, Grippia, Mixosaurus,

and Tholodus, but this feature is probably not synapo-

morphic among the four. The posterior teeth of Grippia and

Chaohusaurus are wide labiolingually (Motani, 1997B), as

in the conical posterior teeth of Utatsusaurus (Motani,

1996), whereas those of the other two genera are long

mesiodistally (i.e., labiolingually compressed) (Merriam,

1910; Peyer, 1939). Durophagy has been proposed for the

four genera, but there is no direct evidence of such feeding

habits (e.g., stomach contents). The jaws of Grippia, Chaohusaurus,

and M. cornalianus are possibly too slender for

durophagy, and their small teeth may have been used for

grasping prey, rather than crushing it (Motani, 1997A,

1997B). The teeth of M.fraasi and M. nordenskioeldii as well

as Tholodus clearly show adaptation for shearing, so they

may have been truly durophagous. The rounded tooth

crowns are associated with the occurrence of multiple

maxillary tooth rows, except in M. cornalianus.

The possession of unusually small teeth is characteristic

for some basal ichthyosaurs (e.g., Motani, 1996,1997B).

The maximum dimension of the crown is smaller than five

percent of the skull width in these teeth, a condition otherwise

unknown in marine reptiles (Massare, 1987). It is

possible that basal ichthyosaurs had a different diet from

all other known marine reptiles.

Another remarkable departure of the crown shape

from the typical conical design is labiolingual flattening,

resulting in the presence of two cutting edges, mesially

and distally. This type of tooth crown is only known in

large ichthyosaurs. The most remarkable teeth are those of

Himalayasaurus, which do not appear very ichthyosaurian

because of the extreme flattening, as well as some swelling,

of their tooth crowns (Motani et al., 1999). Temnodontosau-

rus is also known to have somewhat flattened crowns,

although these coexist with the typical conical type (McGowan,

1974A, 1979B).

Tooth implantation can be described by a combination

of three characters, namely the absence or presence of (1)

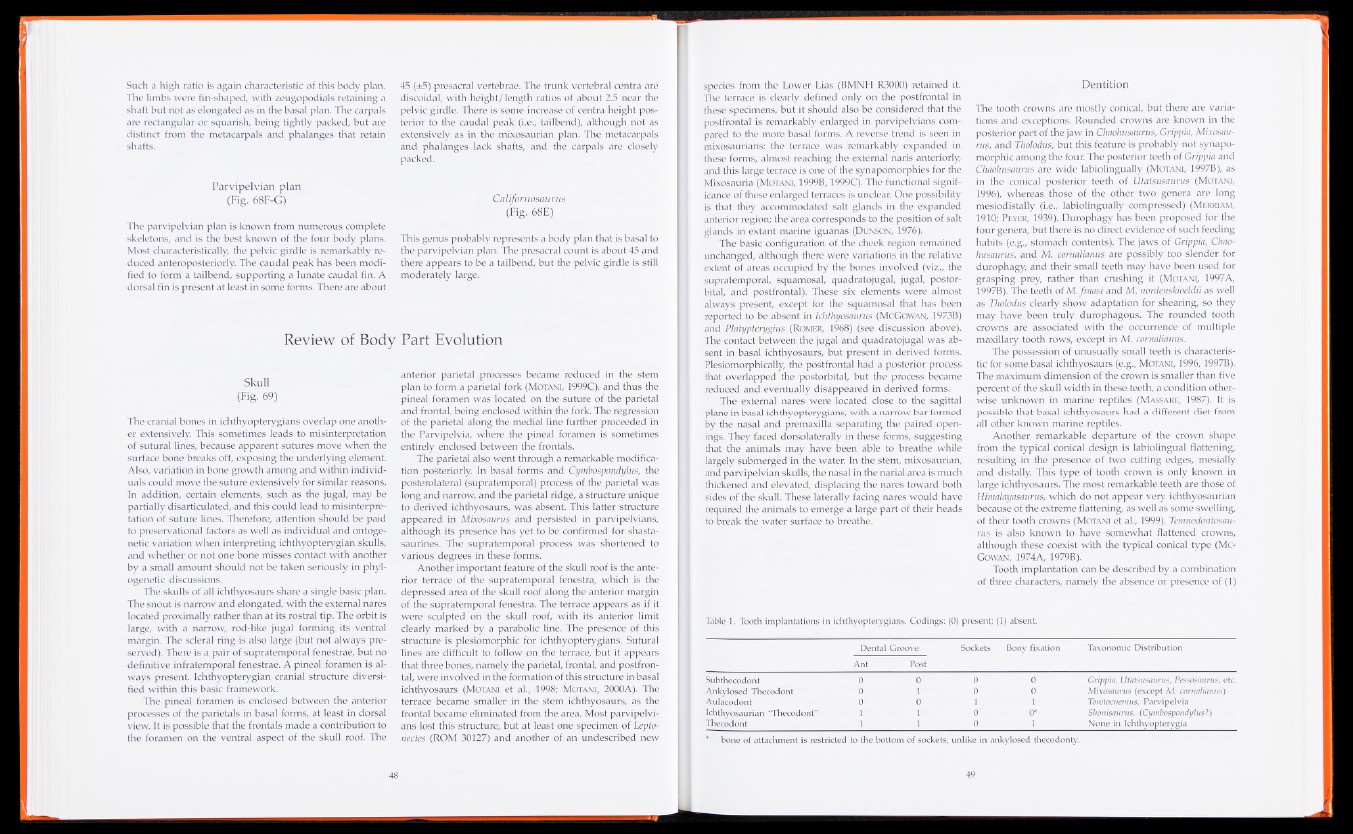

Table 1. Tooth implantations in ichthyopterygians. Codings: (0) present; (1) absent.

Dental Groove Sockets Bony fixation Taxonomic Distribution

Ant Post

Subthecodont 0 0 0 0 Grippia, Utatsusaurus, Pessosaurus, etc.

Ankylosed Thecodont 0 1 0 0 Mixosaurus (except M. cornalianus)

Aulacodont 0 0 1 1 Toretocnemus, Parvipelvia

Ichthyosaurian “Thecodont” 1 1 0 0* Shonisaurus, (Cymbospondylus?)

Thecodont 1 1 0 1 None in Ichthyopterygia

* bone of attachment is restricted to the bottom of sockets, unlike in ankylosed thecodonty.