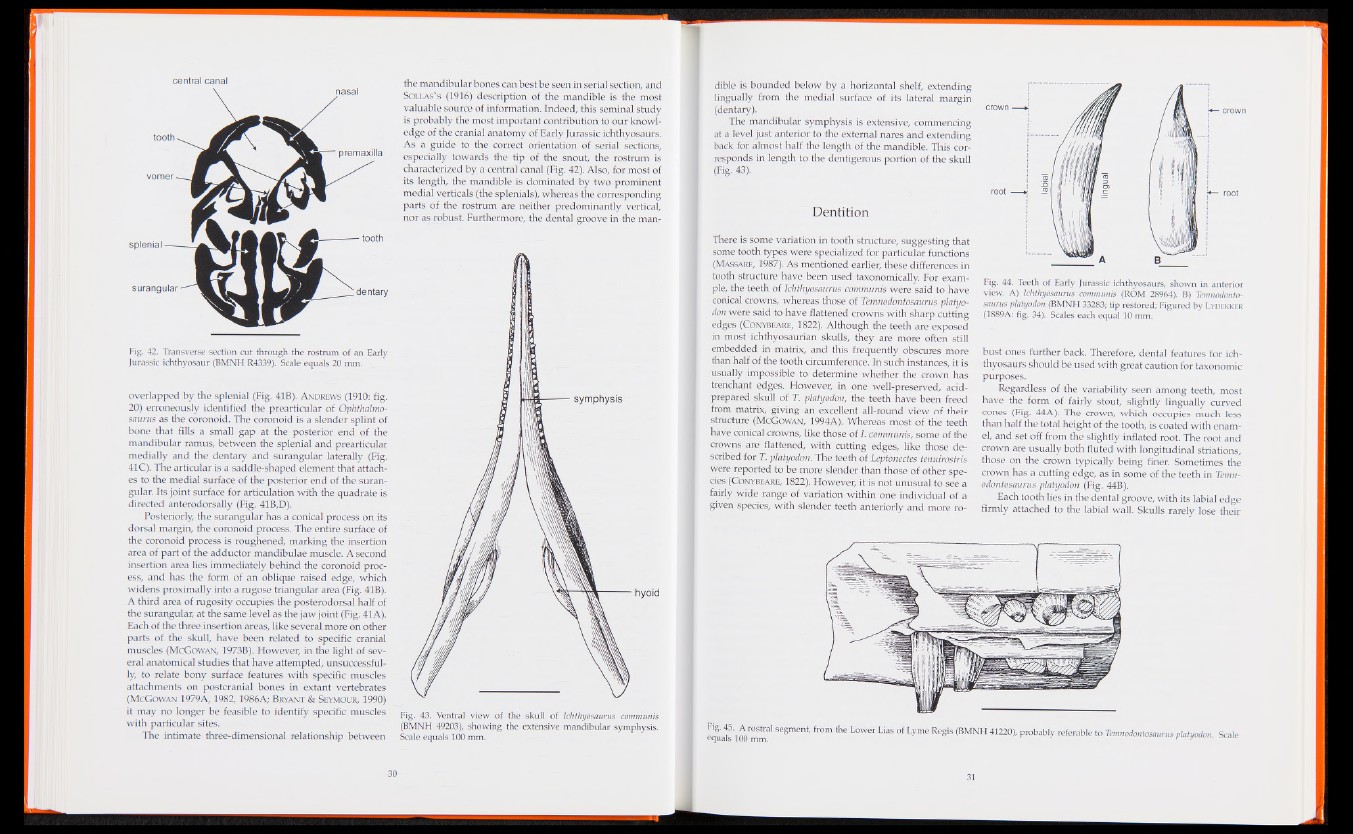

Fig. 42. Transverse section cut through the rostrum of an Early

Jurassic ichthyosaur (BMNH R4339). Scale equals 20 mm.

overlapped by the splenial (Fig. 41B). Andrews (1910: fig.

20) erroneously identified the prearticular of Ophthalmo-

saurus as the coronoid. The coronoid is a slender splint of

bone that fills a small gap at the posterior end of the

mandibular ramus, between the splenial and prearticular

medially and the dentary and surangular laterally (Fig.

41C). The articular is a saddle-shaped element that attaches

to the medial surface of the posterior end of the suran-

gular. Its joint surface for articulation with the quadrate is

directed anterodorsally (Fig. 41B,D).

Posteriorly, the surangular has a conical process on its

dorsal margin, the coronoid process. The entire surface of

the coronoid process is roughened, marking the insertion

area of part of the adductor mandibulae muscle. A second

insertion area lies immediately behind the coronoid process,

and has the form of an oblique raised edge, which

widens proximally into a rugose triangular area (Fig. 41B).

A third area of rugosity occupies the posterodorsal half of

the surangular, at the same level as the jaw joint (Fig. 41 A).

Each of the three insertion areas, like several more on other

parts of the skull, have been related to specific cranial

muscles (McGowan, 1973B). However, in the light of several

anatomical studies that have attempted, unsuccessfully,

to relate bony surface features with specific muscles

attachments on postcranial bones in extant vertebrates

(McGowan 1979A, 1982, 1986A; Bryant & Seymour, 1990)

it may no longer be feasible to identify specific muscles

with particular sites.

The intimate three-dimensional relationship between

the mandibular bones can best be seen in serial section, and

Sollas’s (1916) description of the mandible is the most

valuable source of information. Indeed, this seminal study

is probably the most important contribution to our knowledge

of the cranial anatomy of Early Jurassic ichthyosaurs.

As a guide to the correct orientation of serial sections,

especially towards the tip of the snout, the rostrum is

characterized by a central canal (Fig. 42). Also, for most of

its length, the mandible is dominated by two prominent

medial verticals (the splenials), whereas the corresponding

parts of the rostrum are neither predominantly vertical,

nor as robust. Furthermore, the dental groove in the man-

Fig. 43. Ventral view of the skull of Ichthyosaurus communis

(BMNH 49203), showing the extensive mandibular symphysis.

Scale equals 100 mm.

dible is bounded below by a horizontal shelf, extending

lingually from the medial surface of its lateral margin

(dentary).

The mandibular symphysis is extensive, commencing

at a level just anterior to the external nares and extending

back for almost half the length of the mandible. This corresponds

in length to the dentigerous portion of the skull

(Fig. 43).

Dentition

There is some variation in tooth structure, suggesting that

some tooth types were specialized for particular functions

(Massare, 1987). As mentioned earlier, these differences in

tooth structure have been used taxonomically. For example,

the teeth of Ichthyosaurus communis were said to have

conical crowns, whereas those of Temnodontosaurus platyo-

don were said to have flattened crowns with sharp cutting

edges (Conybeare, 1822). Although the teeth are exposed

in most ichthyosaurian skulls, they are more often still

embedded in matrix, and this frequently obscures more

than half of the tooth circumference. In such instances, it is

usually impossible to determine whether the crown has

trenchant edges. However, in one well-preserved, acid-

prepared skull of T. platyodon, the teeth have been freed

from matrix, giving an excellent all-round view of their

structure (McGowan, 1994A). Whereas most of the teeth

have conical crowns, like those of I. communis, some of the

crowns are flattened, with cutting edges, like those described

for T. platyodon. The teeth of Leptonectes tenuirostris

were reported to be more slender than those of other species

(Conybeare, 1822). However, it is not unusual to see a

fairly wide range of variation within one individual of a

given species, with slender teeth anteriorly and more roB

Fig. 44. Teeth of Early Jurassic ichthyosaurs, shown in anterior

view. A) Ichthyosaurus communis (ROM 28964). B) Temnodontosaurus

platyodon (BMNH 33283; tip restored; Figured by L ydekker

(1889A: fig. 34). Scales each equal 10 mm.

bust ones further back. Therefore, dental features for ichthyosaurs

should be used with great caution for taxonomic

purposes.

Regardless of the variability seen among teeth, most

have the form of fairly stout, slightly lingually curved

cones (Fig. 44A). The crown, which occupies much less

than half the total height of the tooth, is coated with enamel,

and set off from the slightly inflated root. The root and

crown are usually both fluted with longitudinal striations,

those on the crown typically being finer. Sometimes the

crown has a cutting edge, as in some of the teeth in Temnodontosaurus

platyodon (Fig. 44B).

Each tooth lies in the dental groove, with its labial edge

firmly attached to the labial wall. Skulls rarely lose their

e q t S ' Se8ment' &0m * e L°Wer LiaS ° f Lyme RegiS (BMNH 41220)' Probably re£erable to Temnodontosaurus platyodon. Scale