it is necessary to traverse no less than eight snowclad

ridges.

Towards the middle of these mountains, the width

of the plateau upon which the ranges rest diminishes,

and the ridges become fewer in number. Its more

extensive ramifications are noticeable at the western

end, beginning at the sources of the Syr-daria; and

the colossal Thian Shan, that already has lost its

name at its western extremity, finally sinks, like a vast

ruin, into the plains of Turkistan in the form

o f rocky spurs, surrounded by salt marshes and

sands. Kostenko* gives a separate description to

nearly 40 ranges f forming the Thian Shan, some

of which will be alluded to hereafter.

* In Ms “ Turkestanski K ra i,” of

in this description.

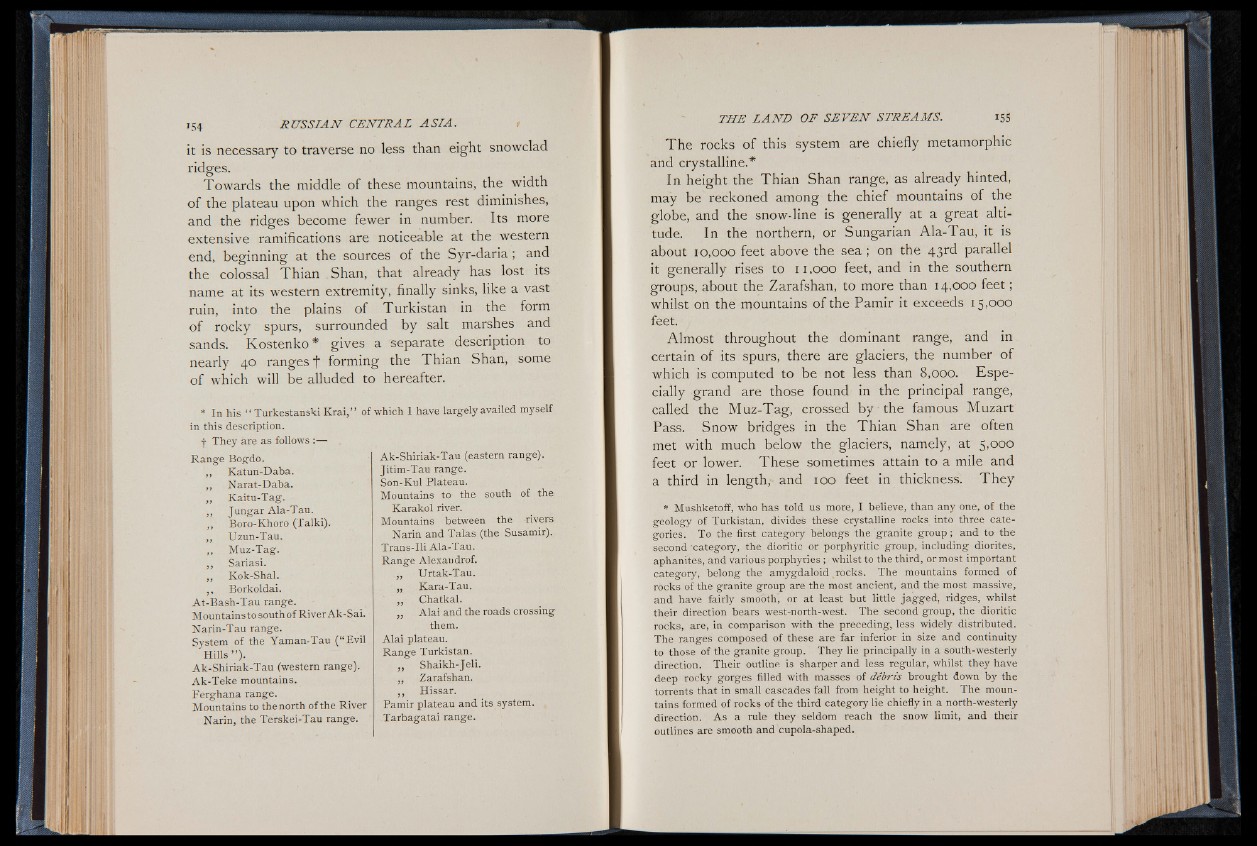

f They are as follows :— .

Range Bogdo.

Katun-Daba.

Narat-Daba.

Kaitu-Tag.

Jungar Ala-Tau.

Boro-Khoro (Talki).

Uzun-Tau.

Muz-Tag.

Sariasi.

Kok-Shal.

Borkoldai.

At-Bash-Tau range.

Mountainsto south of River Ak-Sai.

Narin-Tau range.

System of the Yaman-Tau (“ Evil

H ills ” ).

Ak-Shiriak-Tau (western range).

A k -Tek e mountains.

Ferghana range.

Mountains to the north of the River

Narin, the Terskei-Tau range.

which 1 have largely availed myself

Ak-Shiriak-Tau (eastern range).

Jitim-Tau range.

Son-Kul Plateau.

Mountains to the south of the

Karakol river.

Mountains between the rivers

Narin and Talas (the Susamir).

Trans-Ili Ala-Tau.

Range Alexaudrof.

„ Urtak-Tau.

„ Kara-Tau.

,, Chatkal.

„ A la i and the roads crossing

them.

Alai plateau.

Range Turkistan.

,, Shaikh-Jeli.

„ Zarafshan.

,, Hissar.

Pamir plateau and its system.

Tarbagatai range.

The rocks of this system are chiefly metamorphic

and crystalline.*

In height the Thian Shan range, as already hinted,

may be reckoned among the chief mountains of the

globe, and the snow-line is generally at a great altitude.

In the northern, or Sungarian Ala-Tau, it is

about 10,000 feet above the sea ; on the 43rd parallel

it generally rises to 11,000 feet, and in the southern

groups, about the Zarafshan, to more than 14,000 feet ;

whilst on the mountains of the Pamir it exceeds 15,000

feet.

Almost throughout the dominant range, and in

certain of its spurs, there are glaciers, the number of

which is computed to be not less than 8,000. Especially

grand are those found in the principal range,

called the Muz-Tag, crossed by the famous Muzart

Pass. Snow bridges in the Thian Shan are often

met with much below the glaciers, namely, at 5,000

feet or lower. These sometimes attain to a mile and

a third in length, and 100 feet in thickness. They

* Mushketoff, who has told us more, I believe, than any one, of the

geology of Turkistan,: divides these crystalline rocks into three categories.

To the first category belongs the granite group ; and to the

second ‘category, the dioritic or porphyritic group, including diorites,

aphanites, and various porphyries ; whilst to the third, or most important

category, belong the amygdaloid , rocks. The mountains formed of

rocks of the granite group are the most ancient, and the most massive,

and have fairly smooth^ or at least but little jag ged , ridges, whilst

their direction bears west-north-west. The second group, the dioritic

rocks, are, in comparison with the preceding, less widely distributed.

The ranges composed of these are far inferior in size and continuity

to those of the granite group. They lie principally in a south-westerly

direction. Their outline is sharper and less regular, whilst they have

deep rocky gorges filled with masses of débris brought down by the

torrents that in small cascades fall from height to height. The mountains

formed of rock® of the third category lie chiefly in a north-westerly

direction. As a rule they seldom reach the snow limit, and their

outlines are smooth and cupola-shaped.