joined by some Russian officers who had heard of riiy

conducting the service.

Kostenko says that as a rule “ these Kuldja Catholics

are very lax as to the essentials of their religion. They

wear crosses round their necks, and read prayers in

the Latin language, and they made a request (that

is, of the Russians) that they might be permitted to

display these emblems on the outside of their dress.”

I may add, however, that a very intelligent Russian

Protestant in the region told me that among their own

people the character of the Chinese Christians stands

high, that they do not smoke opium, and that their word

can be relied on. The persistence of this handful of

Chinese in the tenets of their adopted religion, under

such unfavourable circumstances, reminded me of my

crossing the Pacific in 1879 with an American clergyman

who had laboured as a missionary among both

Chinese and Japanese, and who regarded work among

the former as decidedly the more hopeful. The

Japanese he allowed were more readily influenced,

but, like children, they sometimes drop the toy that

has quickly pleased them, whereas, though John

Chinaman takes a longer time to be convinced, he

is, when won, more easily held. I have since

heard that three Roman missionaries have arrived

in Kuldja.

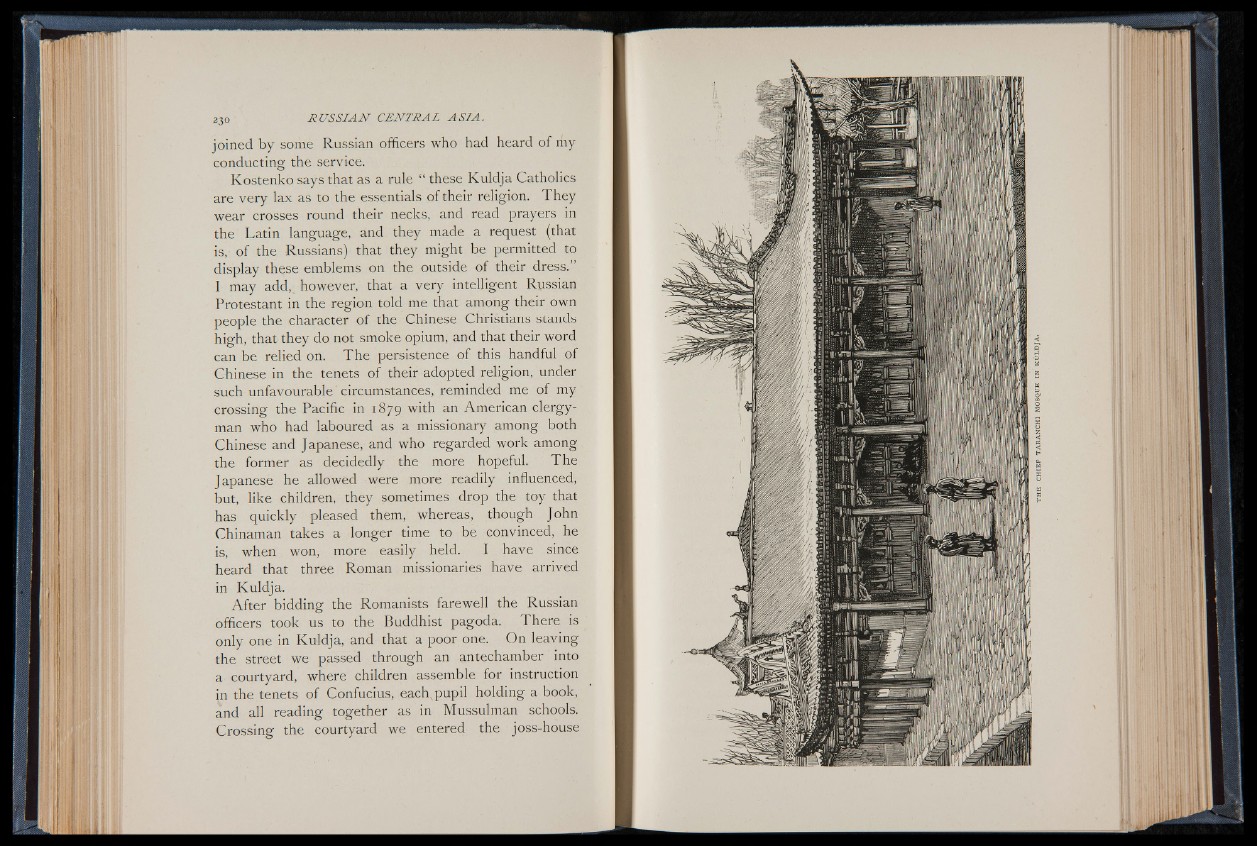

After bidding the Romanists farewell the Russian

officers took us to the Buddhist pagoda. There is

only one in Kuldja, and that a poor one. On leaving

the street we passed through an antechamber into

a courtyard, where children assemble for instruction

in the tenets of Confucius, each, pupil holding a book,

and all reading together as in Mussulman schools.

Crossing the courtyard we entered the joss-house