C H A P T E R X X X I I .

F R OM T A SH K E N D TO K H O JE N D .

Central situation of Tashkend.— Post-road to Jizakh.— The “ Hungry ”

Steppe.— Stations to K h o je n d C k i r c :hik and Angren rivers.— -

Vegetation of Kurama and of Turkistan generally.— Forest trees

and shrubs.— Fruit trees.— Garden and dyeing plants.— Kurama

soil and cultivation of cereals.— Journey from Tashkend.— Steppe

vegetation.— An unruly horse.— Fortified post-stations.— Approach'

to Khojend.

TO the traveller leaving Tashkend, the city is seen

to be well situated, for though not built upon

a river’s bank, yet the snows of the Talasky Ala-Tau

and the springs in the Chatkal mountains send down

sufficient water in the River Chirchik to allow’ canals

diverted therefrom to afford a constant supply. Also

Tashkend is centrally situated in the zone of the watered

region that stretches from the country about Samarkand

to the valleys of Semirechia, and there are paths permitting

of easy communication with the upper valleys

of the Syr, the Talas, and the Chu. I have frequently

noticed in Russia, and even in out-of-the-way places in

Siberia, how fond the people are in summer of leaving

their town houses for a cottage in “ the country and

this practice prevails, with good show of reason, at

Tashkend, where those who possess property iij the

suburbs follow the custom of the natives, and live in

tents in the midst of their gardens. Zengi-Ata, so'uth

of the capital, which the traveller passes on the road

to Chinaz, is a fashionable resort of this kind.

This road goes direct from Tashkend to Samarkand,

a distance of 190 miles. O f this route I need

here speak only of the journey to Jizakh, since I

traversed the remainder coming from Khokand*

We set out for Khojend on Thursday evening,

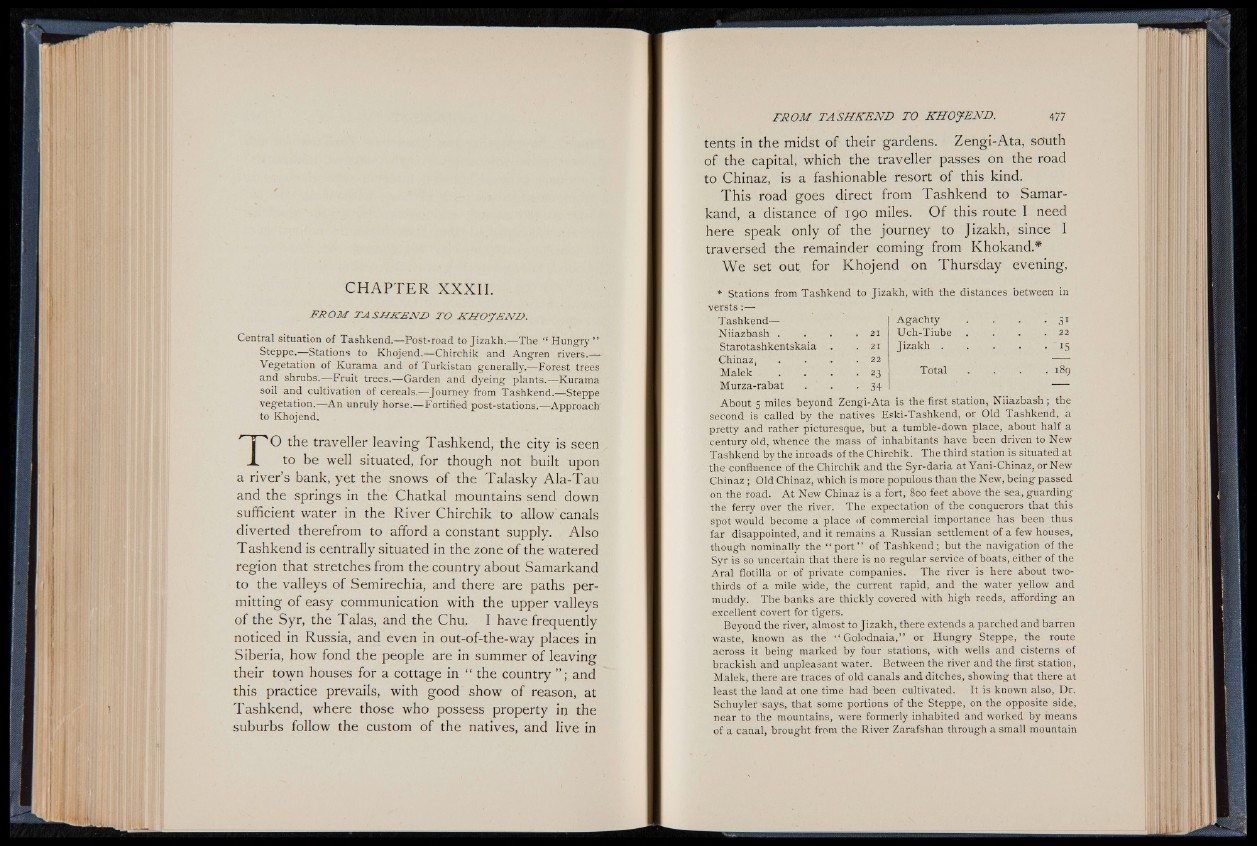

* Stations from Tashkend to Jizakh, with the distances between in

versts

Tashkend— A ga chty ■ - 3 1

Niiazbash . . 21 Uch-Tiube . 22

Starotashkentskaia . 21 Jizakh . • n

Chinaz, . . . 22 —

Malek • 23 Total . 189

Murza-rabat • 34 —

About 5 miles beyond Zengi-Ata is the first station, N iia zb a sh; the

second is called by the natives Eski-Tashkend, or Old Tashkend, a

pretty and rather picturesque, but a tumble-down place, about half a

century old, whence the mass of inhabitants have been driven to New

Tashkend by the inroads of the Chirchik. The third station is situated at

the confluence of the Chirchik and the Syr-daria at Yani-Chinaz, or New

Chinaz ; Old Chinaz, which is more populous than the New, b eing passed

on the road. A t New Chinaz is a fort, 800 feet above the sea, guarding

the ferry over the river. The expectation of the conquerors that this

spot would become a place of commercial importance has been thus

far disappointed, and it remains a Russian settlement of a few houses,

though nominally the “ p o rt” of Tashkend; but the navigation of the

Syr is so uncertain that there is no regular service of boats, either of the

Aral flotilla or of private companies. The river is here about two-

thirds of a mile wide, the current rapid, and the water yellow and

muddy. The banks are thickly covered with high reeds, affording an

excellent covert for tigers.

Beyond the river, almost to Jizakh, there extends a parched and barren

waste, known as the “ Golodnaia,” or Hungry Steppe, the route

across it being marked by four stations, with wells and cisterns of

brackish and unpleasant water. Between the river and the first station,

Malek, there are traces of old canals and ditches, showing that there at

least the land at one time had been cultivated. It is known also, Dr.

Schuyler says, that some portions of the Steppe, on the opposite side,

near to the mountains, were formerly inhabited and worked by means

of a canal, brought from the River Zarafshan through a small mountain