themselves by the convenient circumstance that just

over the south-west frontier, in the neighbourhood of

Biisk and Barnaul (the happy land where, in 1879, I

found good black earth letting at 3%d. an acre), the

peasants can easily grow, in a year, five times as much

corn as they can eat, and when, in 1881, the crop of

their neighbours so completely failed, the official report

says it “ had no particularly bad consequences.” The

reserves of the Tomsk district amply sufficed for the

emergency, and “ there was not even an extraordinary

rise in the price of corn.’ *

The Cossacks are great gardeners ; or, at least, their

wives are ; the husbands also being sometimes driven

thereto by lack of other work. They grow tobacco,

water and other melons, and hemp. The crop for 1881

was 197 tons of tobacco; of hemp, 53 tons; seeds of

flax and other oleaginous plants, 16 tons ; and 1,298,300

melons. The tobacco is of inferior quality, but suited

to local taste. In 1879 the province yielded 292 tons ;

and in 1880, 243 ; but the official return for 1881

was only 194. This last figure, however, is judged

to be too low, because of the male Kirghese and

Cossacks, the former all ‘ snuff,’ and the latter all smoke,

and, since no importation took place, their estimated

requirements of 486 tons must have been supplied by

local culture. The Cossacks make much of their hay,

selling the surplus in townS, especially* in Pavlodar,

or to the Kirghese. The poor or thriftless Cossack

sells his crop on the ground; but the rich reap for

themselves, or with the help of the Kirghese, paying

*T h e Cossack and settled populations even stocked their corn reserves,

as usual in other parts of the Empire, as a precaution against

famine. In 1880 there were in the province 69 store-houses, and a t the

end of 1881 there remained available 2,354 quarters of corn, besides

6,634 quarters due on account of 'loans or arrears.

in wages, or in kind with a third or half the crop. The

dry season of 1881 was unfavourable for hay, and

though 65,000 tons were cut by the settlers, which was

one-fourth in excess of the preceding year, it did not

suffice to feed the herds without breaking in upon the

reserves.

Cattle-breeding constitutes the chief means of subsistence,

not only of the nomads (who form more than

89 per cent, of the population), but also of a certain

portion of the settled inhabitants of the province, especially

about Karkarali and Pavlodar, where, to a great

extent, the climate and soil are unsuitable for agriculture.

No attempt is made to improve the breed of the

Steppe cattle, the settlers conducting their operations

partly on the Kirghese system, with this difference,

that instead of sheep, which constitute the first article of

Kirghese management, their attention is chiefly devoted

to horned cattle, though making less of milk produce

than the nomads. According to official information,

the number of beasts in the province in 1880 amounted

in all to 3,081,082.

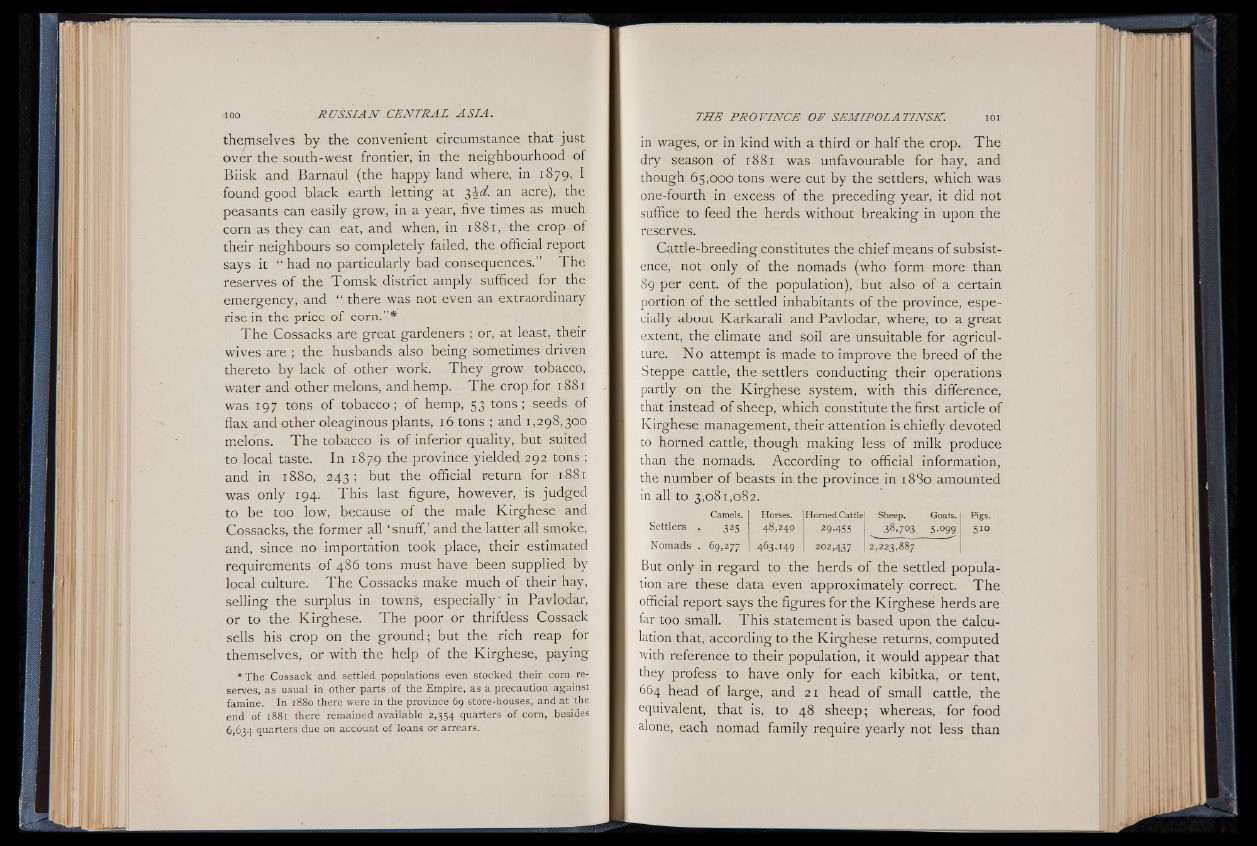

Camels.

Settlers 325

Nomads 69,277

Horses. Horned Cattle ‘ Sheep. Goats. Pigs.

48,240 29 ’455 38,703 5-099 510

463,149 202,437 2,223,887

But only in regard to the herds of the settled population

are these data even approximately correct. The

official report says the figures for the Kirghese herds are

far too small. This statement is based upon the Calculation

that, according to the Kirghese returns, computed

with reference to their population, it would appear that

they profess to have only for each kibitka, or tent,

664 head of large, and 21 head of small • cattle, the

equivalent, that is, to 48 sheep; whereas, for food

alone, each nomad family require yearly not less than