Semipolatinsk, whither we were accompanied by the

police-master. Here a felon might have to remain

as long as four years. There were 78 prisoners, of

whom 25 were Kirghese. The latter are sometimes

birched with rods up to 60 stripes— an appeal to their

feelings that is much more effectual than the leisure

of mere confinement, and the supply of better food

than they habitually get outside. No less than 20

of the prisoners were accused of murder, and 35 of

robbery. The morals of the inmates at Semipolatinsk

seemed to me better cared for than in most Russian

prisons ; for not only did the prisoners attend church

every Sunday, and often on feast days, but a sermon

was said to be read to them after every service, and,

what I have never before heard of in a Russian

prison, a priest came every Tuesday to the diningroom,

and explained the Scriptures.

There was a religious curiosity in this prison in the

person of a Raskolnik or dissenter, whose equal for

sectarian ignorance and self-righteousness I have not

asylums so hyper-clean, even in Russia, that, to use a familiar expression,

“ one might ha ve 'e aten off the floor.” Compared with

buildings such as these, the average Russian prison must be allowed

to be “ dirty,” or, compared with a countess’ s drawing-room, even

“ filthy.” But if such an expression should convey to a reader’ s mind

what it did convey to the mind of the friend who pointed out the passage

to me, and who thought faecal filth was intended thereby, then such

language is a libel. The nearest resemblance I can think of, for the

moment, to the floor of a Russian prison is the floor of a dirty national

school, over which a pack of boys have run for a w eek with the dirty boots

of winter. I do not remember ever seeing anything in Russian prisons

worse than this, and in the majority of cases things were better; whilst

as for the atmosphere, and the exaggerations talked about it, I have

been in Russian prisons at all hours of the day, before some of the

prisoners were up in the morning, and just before they were going to

bed at n ight, but in none was the air so vitiated as that which some of the

peasants to my knowledge chose to have in their own houses, or, to

come nearer home, such a s I used to meet with in parochial visiting when

curate of Greenwich.

often met. What had brought him to prison I do

not exactly know ; but we were told he came from the

Urals, and would neither serve in the army as a

conscript, nor obey the Government. I imagine

that he belonged to the narrowest sect of the

Star overs, or old believers, who regard Peter the

Great as Antichrist, and set immense store by old

ikons or sacred pictures, and ancient service books.

The only things this man possessed were an old

ikon, and a Liturgy and daily prayers in manuscript.

Such idols did he make of these that I believe he

would have parted with twenty years of his life rather

than one of his treasures. I need hardly say he

rejected my offer when I asked whether he would

sell them. O f course I could not but in a fashion

admire his steadfastness, and, thinking to meet his

prejudice against reading the Bible in modern Russ,

I offered him a New Testament in Sclavonic; but

he declined it, saying that he did not want it. Thus

he preferred to be confined to the book his own hands

had written, to exercising his mind and heart in

reading that which he had been taught to regard as

the Word of God. In this prison I left matter for the

prisoners to read, and sent to the Governor, General

Protzenko, a sufficiency for the remaining 5 prisons,

and the 17 hospitals, of the province.*

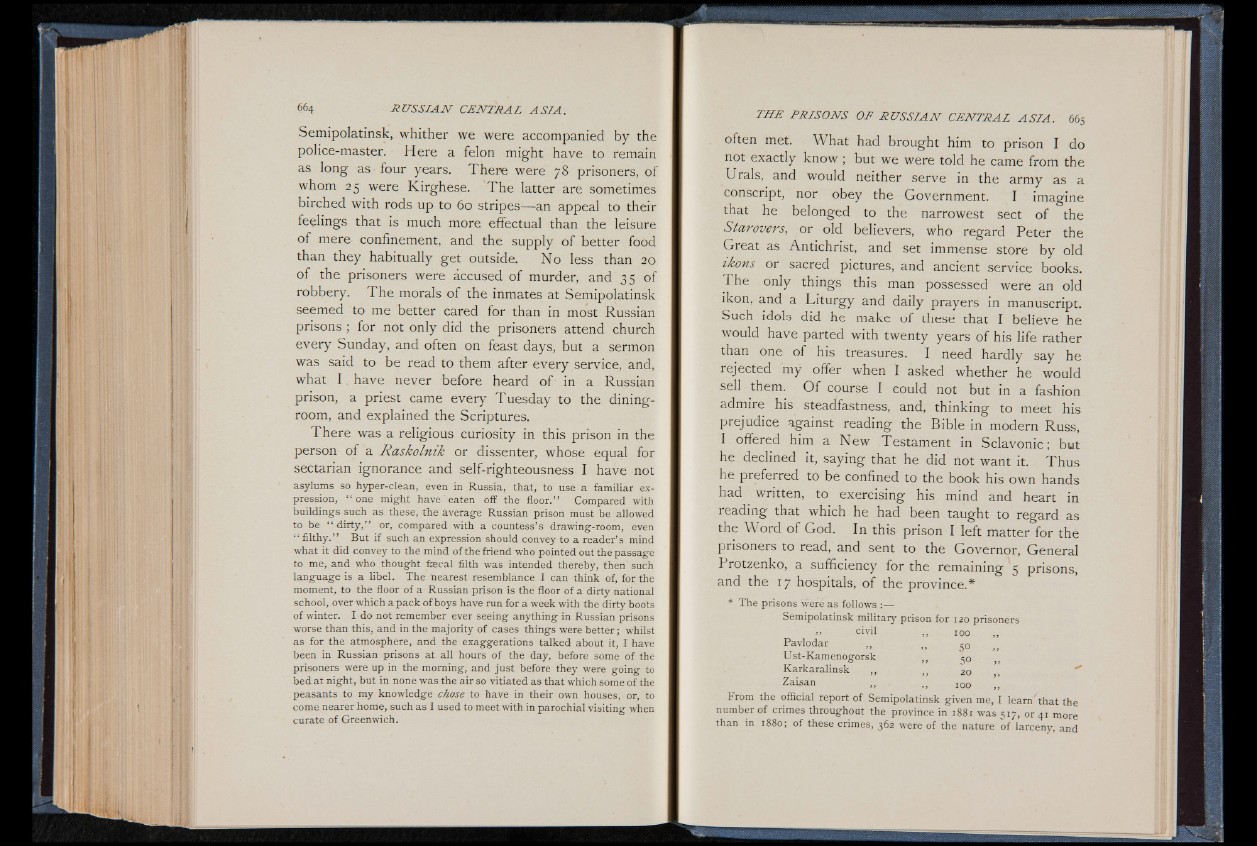

* The prisons were as follows :— \

Semipolatinsk military prison for 120 prisoners

» civil „ IOo

Pavlodar ,, >( r0

Ust-Kamenogorsk ,, c0

Karkaralinsk ,, , 2o

Z3.1s3.11 } ^ , IOO

From the official report of Semipolatinsk given me, I learn that the

number of crimes throughout the province in 1881 was 517, or 41 more

than in 1880; of these crimes, 362 were of the nature of larceny, and