and I heard nothing of any prison.* This was the

first town we had entered where Muhammadans were

so numerous, and I had not yet forgotten the warning

given me in Omsk as to the danger of offering them

the Scriptures. Nor did I know how such a course

would be regarded by the Chinese. When going to

the bazaars next day, howeyer, I took in the chaise

a large bag filled with Scriptures, and whilst looking

here and there for curios to purchase, I presently

offered for sale a copy of the Gospels in Chinese for

5 kopecks. It was bought and immediately examined,

with the result that others came to buy, and those to

whom I had sold returned to purchase more. I then

offered the New Testament for 40 kopecks, and the

Bible for 60 kopecks, and was amused to see them

comparing the size of the Bible with that of the

Gospels, and so reckoning what ought to be the price

of the latter from the proportionate thickness of the

former. I was now besieged by purchasers, who

jumped at my offers. One man wished to buy wholesale,

but fearing that he would re-sell them at exorbitant

prices, I preferred to dispose of them myself,

and soon came to the end of my Chinese stock. But

the Mussulmans showed equal eagerness to get Tatar

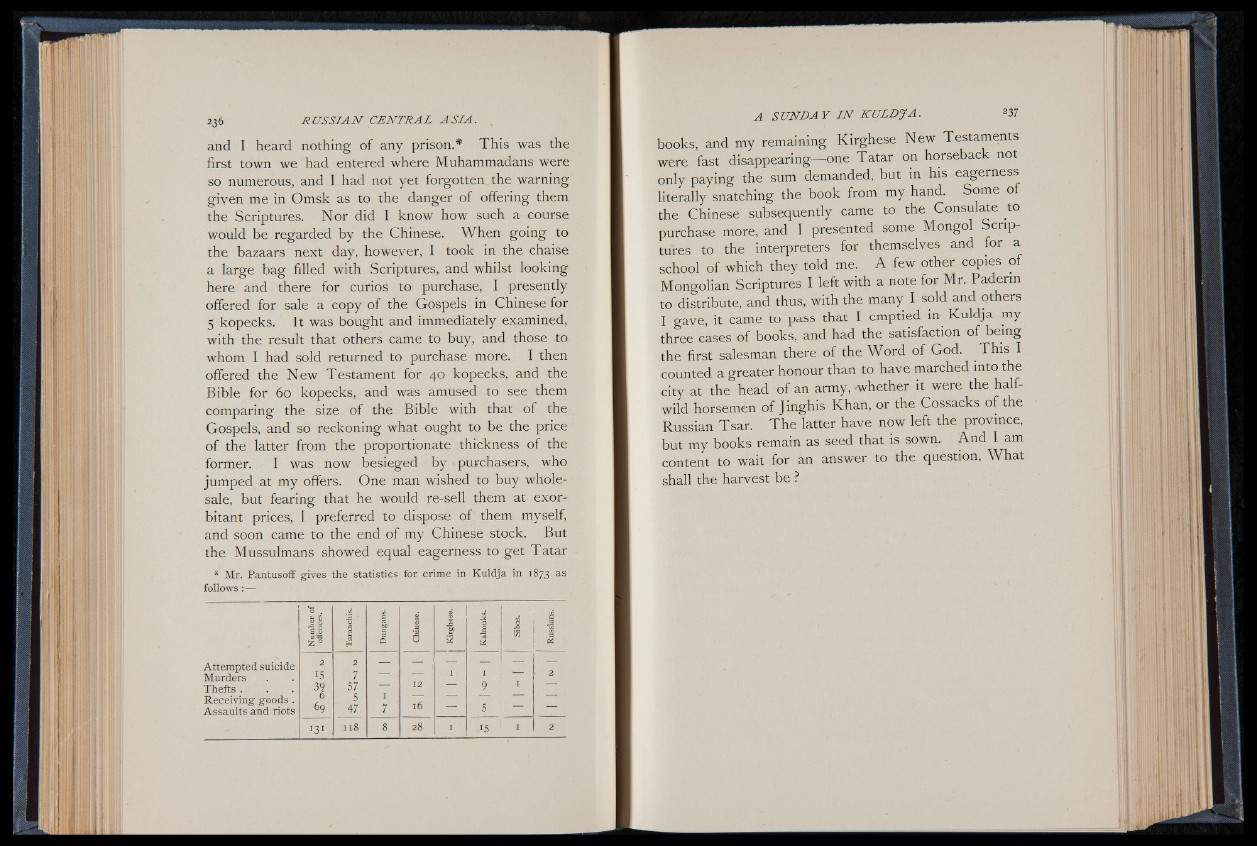

* Mr. Pantusoff gives the statistics for crime in Kuldja in 1873 as

follows :—

Attempted suicide

Murders

Thefts .

Receiving goods .

Assaults and riots

15I69

131

7

,57

5

47

12

16

28

i9

5

Ü

books, and my remaining Kirghese New Testaments

were fast disappearing— one Tatar on horseback not

only paying the sum demanded, but in his eagerness

literally snatching the book from my hand. Some of

the Chinese subsequently came to the Consulate to

purchase more, and I presented some Mongol Scriptures

to the interpreters for themselves and for a

school of which they told me. A few other copies of

Mongolian Scriptures I left with a note for Mr. Paderin

to distribute, and thus, with the many I sold and others

I gave, it came to pass that I emptied in Kuldja my

three cases of books, and had the satisfaction of being

the first salesman there of the Word of God. This I

counted a greater honour than to have marched into the

city at the head of an army, 'whether it were the halfwild

horsemen of Jinghis Khan, or the Cossacks of the

Russian Tsar. The latter have now left the province,

but my books remain as seed that is sown. And I am

content to wait for an answer to the question, What

shall the harvest be ?