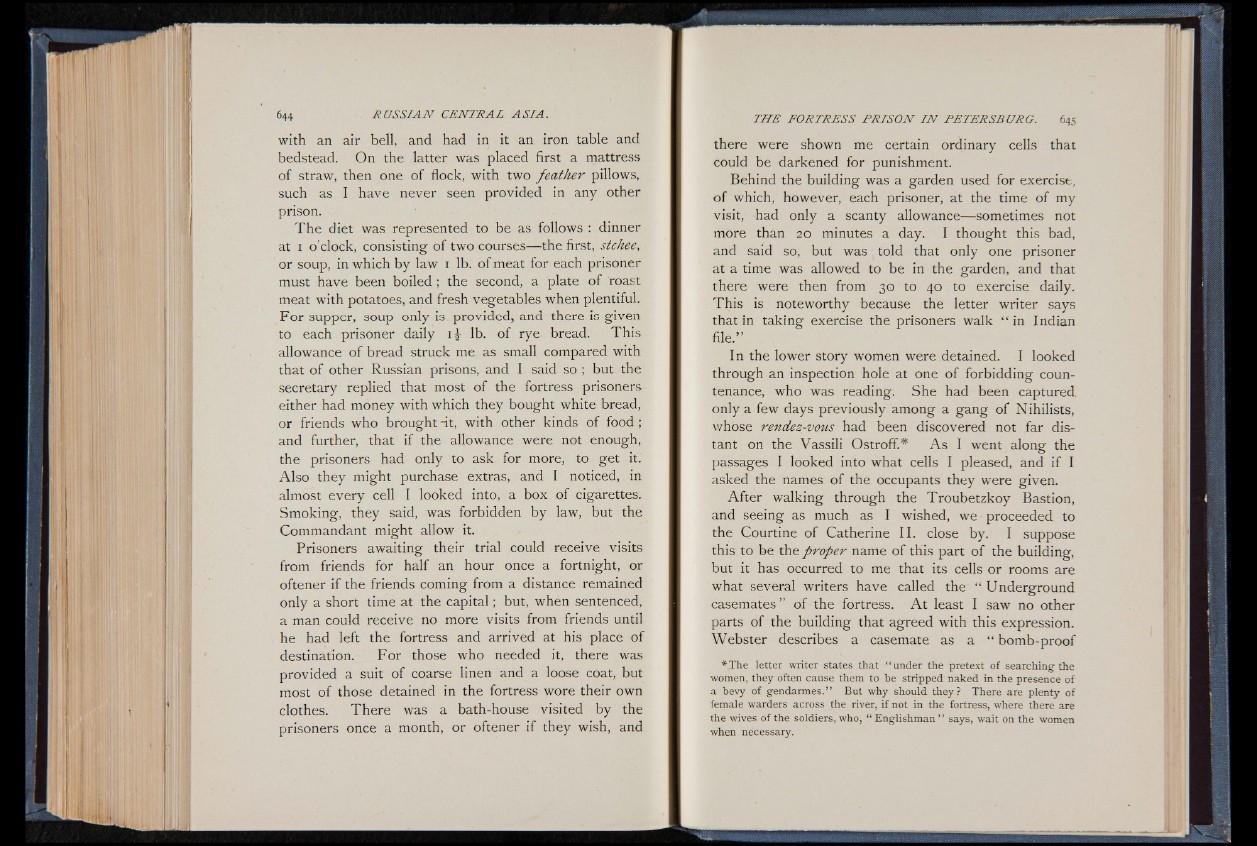

with an air bell, and had in it an iron table and

bedstead. On the latter was placed first a mattress

of straw, then one of flock, with two feather pillows,

such as I have never seen provided in any other

prison.

The diet was represented to be as follows : dinner

at i o’clock, consisting of two courses— the first, stchee,

or soup, in which by law i lb. of meat for each prisoner

must have been boiled ; the second, a plate of roast

meat with potatoes, and fresh vegetables when plentiful.

For supper, soup only is provided, and there is given

to each prisoner daily i j lb. of rye- bread. This

allowance of bread struck me as small compared with

that of other Russian prisons, and I said so ; but the

secretary replied that most of the fortress prisoners

either had money with which they bought white bread,

or friends who brought -it, with other kinds of food ;

and further, that if the allowance were not enough,

the prisoners had only to ask for more, to get it.

Also they might purchase extras, and I noticed, in

almost every cell I looked into, a box of cigarettes.

Smoking, they said, was forbidden by law, but the

Commandant might allow it.

Prisoners awaiting their trial could receive visits

from friends for half an hour once a fortnight, or

oftener if the friends coming from a distance remained

only a short time at the capital; but, when sentenced,

a man could receive no more visits from friends until

he had left the fortress and arrived at his place of

destination. For those who needed it, there was

provided a suit of coarse linen and a loose coat, but

most of those detained in the fortress wore their own

clothes. There was a bath-house visited by the

prisoners once a month, or oftener if they wish, and

there were shown me certain ordinary cells that

could be darkened for punishment.

Behind the building was a garden used for exercise,

of which, however, each prisoner, at the time of my

visit, had only a scanty allowance— sometimes not

more than 20 minutes a day. I thought this bad,

and said so, but was told that only one prisoner

at a time was allowed to be in the garden, and that

there were then from 30 to 40 to exercise daily.

This is noteworthy because the letter writer says

that in taking exercise the prisoners walk “ in Indian

file.”

In the lower story women were detained. I looked

through an inspection hole at one of forbidding countenance,

who was reading. She had been captured,

only a few days previously among a gang o f N ihilists,

whose rendez-vous had been discovered not far distant

on the Vassili Ostroff.# As I went along the

passages I looked into what cells I pleased, and if I

asked the names of the occupants they were given.

After walking through the Troubetzkoy Bastion,

and seeing as much as I wished, we proceeded to

the Courtine of Catherine II. close by. I suppose

this to be the proper name of this part of the building,

but it has occurred to me that its cells or rooms are

what several writers have called the “ Underground

casemates ” of the fortress. A t least I saw no other

parts of the building that agreed with this expression.

Webster describes a casemate as a “ bomb-proof

*T h e letter writer states that “ under the pretext of searching-the

women, they often cause them to be stripped naked in the presence of

a bevy of gendarmes.” But why should they? There are plenty of

female warders across the river, if not in the fortress, where there are

the wives of the soldiers, who, “ Englishman ” says, wait on the women

when necessary.