We then went home, thinking to spend a quiet evening

; but, having a letter of introduction to a native

merchant, I did not like to omit the friendly mission

and proposed accordingly to call. My host, however,

decided that it would be more in keeping with their

custom with the natives to send for the merchant to

come to me, which he did. When the man discovered

that I had brought an introduction all the way from

Moscow, he entreated that, though late, we would

honour him with a visit. Accordingly, Sevier and I

were conducted to this merchant’s house, which I was

glad to see as a specimen of a native interior. We

had been introduced at Tashkend, as I have said, to a

rich Jew, in whose house the reception-room closely

resembled that of the merchant at Khokand. We saw

something too at Tashkend of the women o f the house,

who were dressed in Sart fashion, but were not veiled.

W e were not introduced to them, though they did not

appear to think our presence strange, and they were

evidently not kept in seclusion. In the merchant’s

house at Khokand we saw not a shadow of a female,

but were shown into a room carpeted, indeed, but

without furniture, the principal attractions of the

chamber to us being a number of niches in the wall,

wherein were placed crockery, pans, teapots, and

earthenware goods from Russia and China. In due

time was brought in a small, low, round table with

refreshments, near which our host squatted on the

ground, whilst we were provided with chairs so high

that we had to stoop to help ourselves from the festive

board. I invited questions concerning the country we

came from, whereupon the merchant asked about our

commerce, and the chief kinds of merchandise in

England. My answers interested him, especially when

I went on to tell him that we had railways by which

we could travel the distance from Khokand to Tashkend

in four or five hours.

On returning to M. Ushakoff, he showed us some

sticks of opium that had been seized as contraband,

and also some coats of mail that were in use by the

natives when the town was taken. After this we

walked in the garden. It was a beautiful night at the

end of September, but not at all cold, and I wished

that I could have stayed longer in the province. It

would have been easy to drive round the southern half

on the post-road through Novi Marghilan to Andijan,

whence there is a carriage-road back through the

northern half of the province, by way of Namangan

and Chust to Khokand, or, again, there is a post-road

from Andijan to Osh.* From Osh there is a route 250

miles long to Kashgar.t

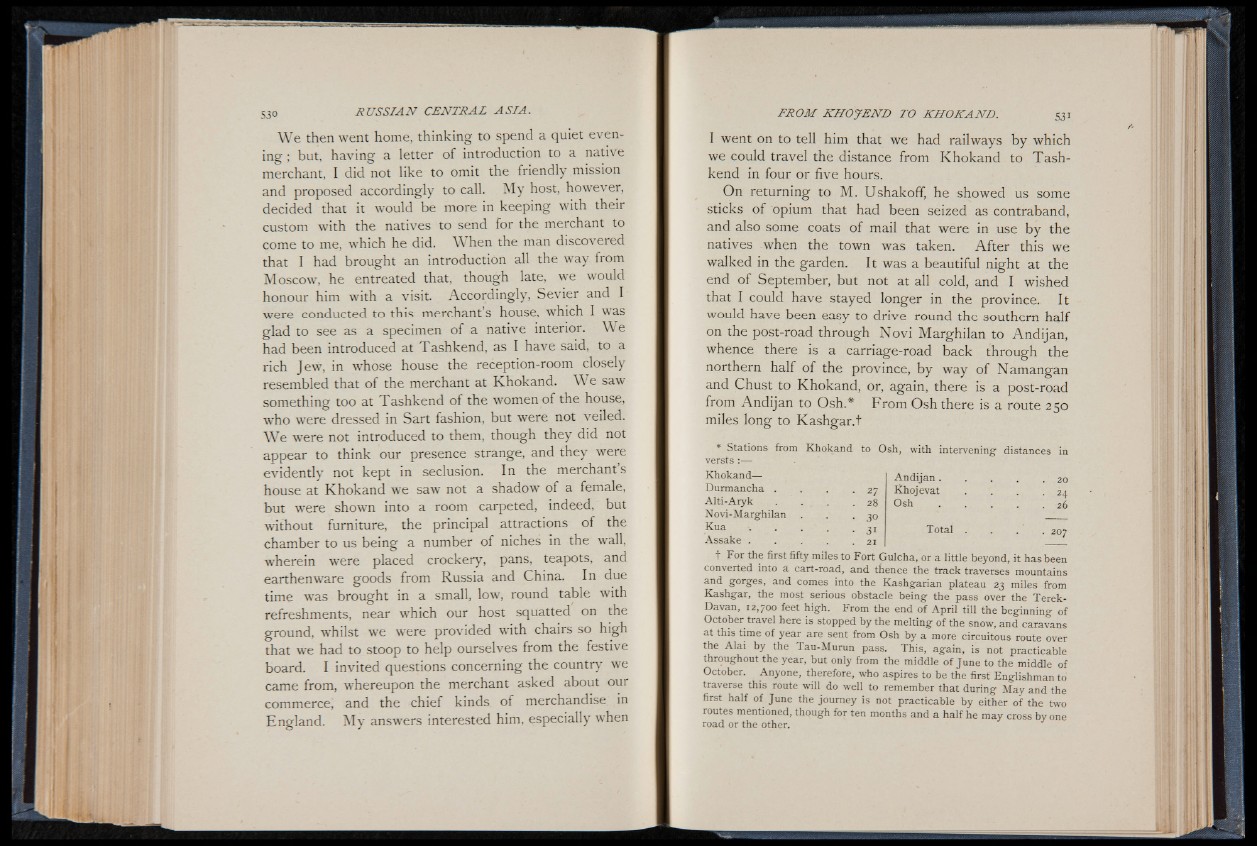

* Stations from Khokand to Osh, with intervening distances in

versts :— -

Khokand—

Durmancha .

Alti-Aryk

N ovi- Marghilan

Kua

Assake .

27

28

30

31

21

Andijan .

Khoievat

Osh

Total

24

26

207

t For the first fifty miles to Fort Gulcha, or a little beyond, it has been

converted into a cart-road, and thence the track traverses mountains

and gorges, and comes into the Kashgarian plateau 23 miles from

Kashgar, the most serious obstacle being the pass over the Terek-

Davan, 12,700 feet high. From the end of April till the beginning of

October travel here is stopped by the melting of the snow, and caravans

a t this time of year are sent from Osh by a more circuitous route over

the A la i by the Tau-Murun pass. This, again, is not practicable

throughout the year, but only from the middle of June to the middle of

October. Anyone, therefore, who aspires to be the first Englishman to

traverse this route will do well to remember that during May and the

first half of June the journey is not practicable by either of the two

routes mentioned, though for ten months and a half he may cross by one

road or the other.