as often freed by the active natives running along the

water’s edge, spaces of cultivated ground often gay with

the yellow flower of the rape wherever the karewas

presented surface enough, and at long intervals villages

of square, wooden cabins and carved boxlike shrines in

a setting of great trees with flowery undergrowth of

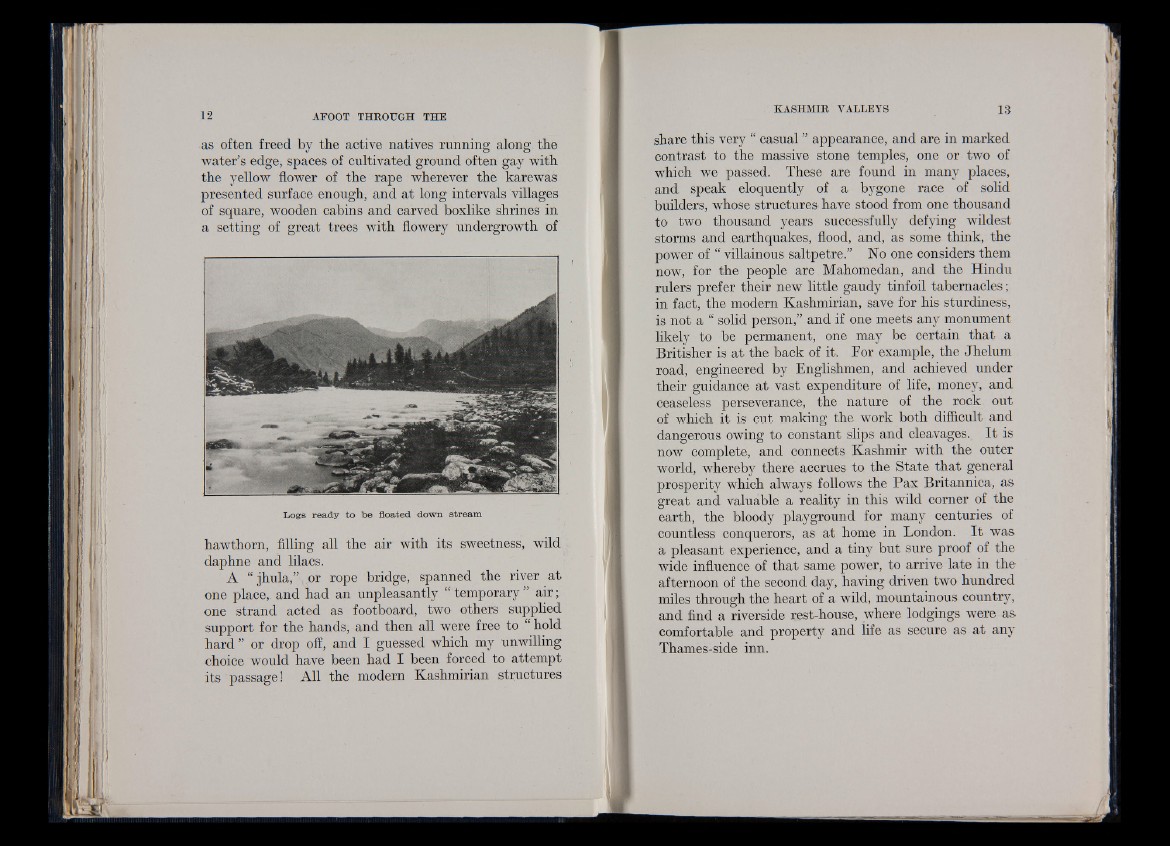

Logs r eady to be floated down stream

hawthorn, filling all the air with its sweetness, wild

daphne and lilacs.

A “ jhula/Vor rope bridge, spanned the river at

one place, and had an unpleasantly “ temporary ” a ir;

one strand acted as footboard, two others supplied

support for the hands, and then all were free to “ hold

h a rd ” or drop off, and I guessed which my unwilling

choice would have been had I been forced to attempt

its passage! All the modern Kashmirian structures

share this very “ casual ” appearance, and are in marked

contrast to the massive stone temples, one or two of

which we passed. These are found in many places,

and speak eloquently of a bygone race of solid

builders, whose structures have stood from one thousand

to two thousand years successfully defying wildest

storms and earthquakes, flood, and, as some think, the

power of “ villainous saltpetre.” No one considers them

now, for the people are Mahomedan, and the Hindu

rulers prefer their new little gaudy tinfoil tabernacles;

in fact, the modem Kashmirian, save for his sturdiness,

is not a “ solid person,” and if one meets any monument

likely to be permanent, one may be certain that a

Britisher is at the back of it. For example, the Jhelum

road, engineered by Englishmen, and achieved under

their guidance at vast expenditure of life, money, and

ceaseless perseverance, the nature of the rock out

of which it is cut making the work both difficult and

dangerous owing to constant slips and cleavages. I t is

now complete, and connects Kashmir with the outer

world, whereby there accrues to the State that general

prosperity which always follows the Pax Britannica, as

great and valuable a reality in this wild corner of the

earth, the bloody playground for many centuries of

countless conquerors, as at home in London. I t was

a pleasant experience, and a tiny but sure proof of the

wide influence of that same power, to arrive late in the

afternoon of the second day, having driven two hundred

miles through the heart of a wild, mountainous country,

and find a riverside rest-house, where lodgings were as

comfortable and property and life as secure as at any

Thames-side inn.