At intervals during the night the soughing of the

wind, the swish of the rain, the sound of the swift

stream—swollen far beyond its normal size—replaced

the soft mutterings of the woodland heard during the

preceding night, and effectually prevented sleep, so that

I was quite ready to dress by daybreak and be off on the

chance of a sight of Nanga Parbat, in case he should

reveal himself as is his wont in the early morning

sunlight.

Floods of rain blotted out all view, and kept me in

my tent during the greater part of the day, and reduced

me to that becoming state of humility in which one

welcomes a moment or too of sunlight as an unexpected

blessing, and a dry islet anywhere as a realm of the

blessed. My entourage said so visibly by their expression,

“We told you so,” that my pride forbade me

ordering a move to drier regions. Moreover, I had all

along felt that Nanga Parbat was the shrine of my

p ilg rim a g e, and, as it was impossible to get a nearer

view without many long and very difficult marches,

necessitating a far larger staff than I possessed, I felt

obliged either to wait with patience till he chose to reveal

himself to his waiting worshipper, or own myself

conquered by circumstances.

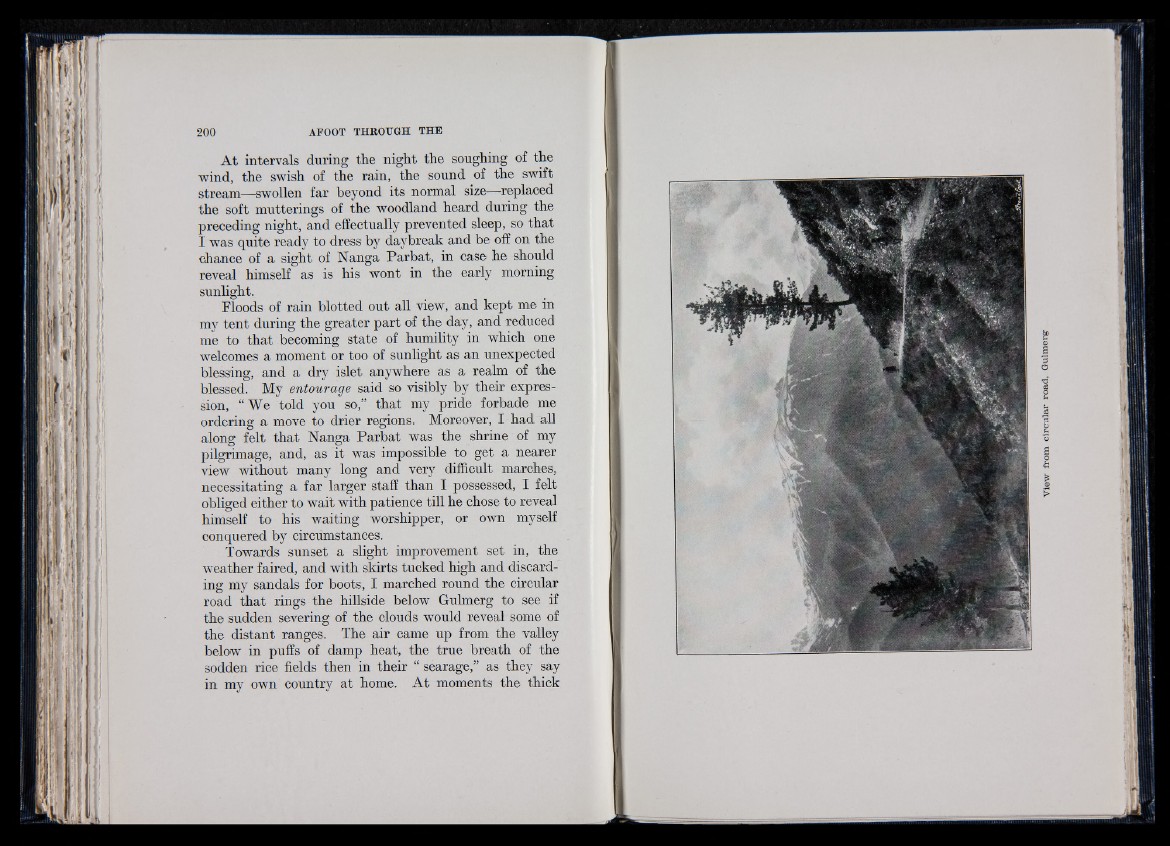

Towards sunset a slight improvement set in, the

weather faired, and with skirts tucked high and discarding

my sandals for boots, I marched round the circular

road that rings the hillside below Gulmerg to see if

the sudden severing of the clouds would reveal some of

the distant ranges. The air came up from the valley

below in puffs of damp heat, the true breath of the

sodden rice fields then in their “ searage,” as they say

in my own country at home. At moments the thick

View from circular road, Gulmerg