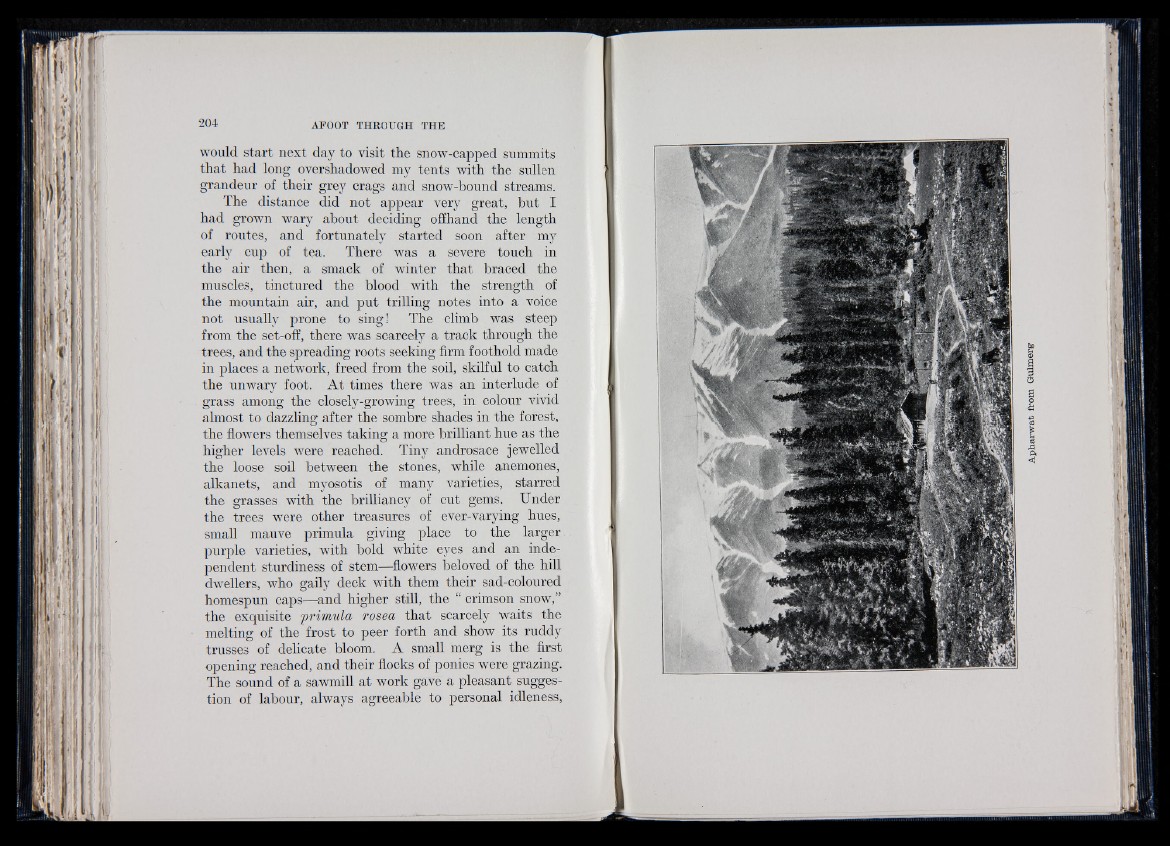

would start next day to visit the snow-capped summits

that had long overshadowed my tents with the sullen

grandeur of their grey crags and snow-bound streams.

The distance did not appear very great, but I

had grown wary about deciding offhand the length

of routes, and fortunately started soon after my

early cup of tea. There was a severe touch in

the air then, a smack of winter that braced the

muscles, tinctured the blood with the strength of

the mountain air, and put trilling notes into- a voice

not usually prone to sing! The climb was steep

from the set-off, there was scarcely a track through the

trees, and the spreading roots seeking firm foothold made

in places a network, freed from the soil, skilful to catch

the unwary foot. At times there was an interlude of

grass among the closely-growing trees, in colour vivid

almost to dazzling after the sombre shades in the forest,

the flowers themselves taking a more brilliant hue as the

higher levels were reached. Tiny androsace jewelled

the loose soil between the stones, while anemones,

alkanets, and myosotis of many varieties, starred

the grasses with the brilliancy of cut gems. Under

the trees were other treasures of ever-varying hues,

small mauve primula giving place to the larger

purple varieties, with bold white eyes and an independent

sturdiness of stem—flowers beloved of the hill

dwellers, who gaily deck with them their sad-coloured

homespun caps—and higher still, the “ crimson snow,”

the exquisite 'primula rosea that scarcely waits the

melting of the frost to peer forth and show its ruddy

trusses of delicate bloom. A small merg is the first

opening reached, and their flocks of ponies were grazing.

The sound of a sawmill at work gave a pleasant suggestion

of labour, always agreeable to personal idleness,