and the mountains pass out of immediate sight ; but the

woods line it with continuous beauty, and in the waning

afternoon every white trunk on the eastern shore meets

its image in the clear water.

At Tamanth^ the river returns again to its mountains,

which loom up blue and majestic in bold outline against

the s k y ; waves upon waves of them, ramparts, and

peaks, and shadowy valleys. The sun, passing on to

the portals of night, sends his last splendour abroad

from behind the

clouds that marshal,

his retreat. Wide

shafts of ligh t

flame in fans over

the sp a c e s o f

h e aven . From

cloud to cloud the

fires race until,

through infinite

gradations, the day

maung-kan runs out to its close.

Tamanth^ is the last British outpost on the Chindwin.

It is garrisoned by half a hundred fighting men, under

the command of a Sikh officer. The steamer has

scarcely done screaming, the gangway planks are not

yet slippery with the wet footprints of the crew, when

he comes hurrying along, under the stress of a tight

uniform and long sword dangling by his side, to , pay

his respects. White man to him is synonymous with

ruler, and three Englishmen do not come this way in

448

the year. His men

are hastily forming

up on the parade

ground, and he is

disappointed that

they are not to be

inspected. No one

e v e r comes to

T amanthe except

for some such purpose.

The Subah-

dar practically rules

here alone.

Two miles beyond

Tamanthe is

the v illa g e o f

Htwatwa, on the

further shore of

the Nam Talei,

which comes down

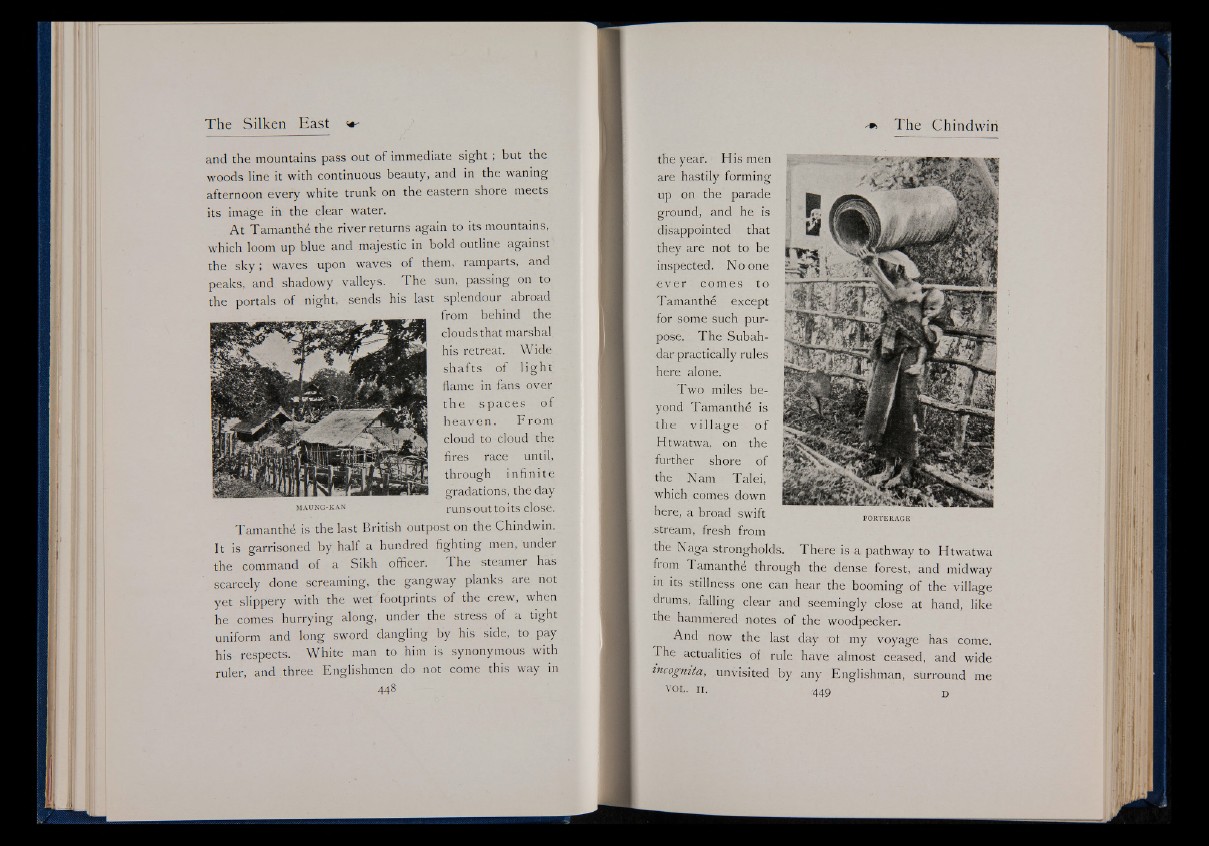

here, a broad swift p o r t e r a g e

.stream, fresh from

the Naga strongholds. There is a pathway to Htwatwa

from Tamanthd through the dense forest, and midway

in its stillness one can hear the booming of the village

drums, falling clear and seemingly close at hand, like

the hammered notes of the woodpecker.

And now the last day t>1 my voyage has come.

The actualities of rule have almost ceased, and wide

incognita, unvisited by any Englishman, surround me

v o l . 11. 449 D