what he needs, and puts the price into a little cup in

the middle of the tray.

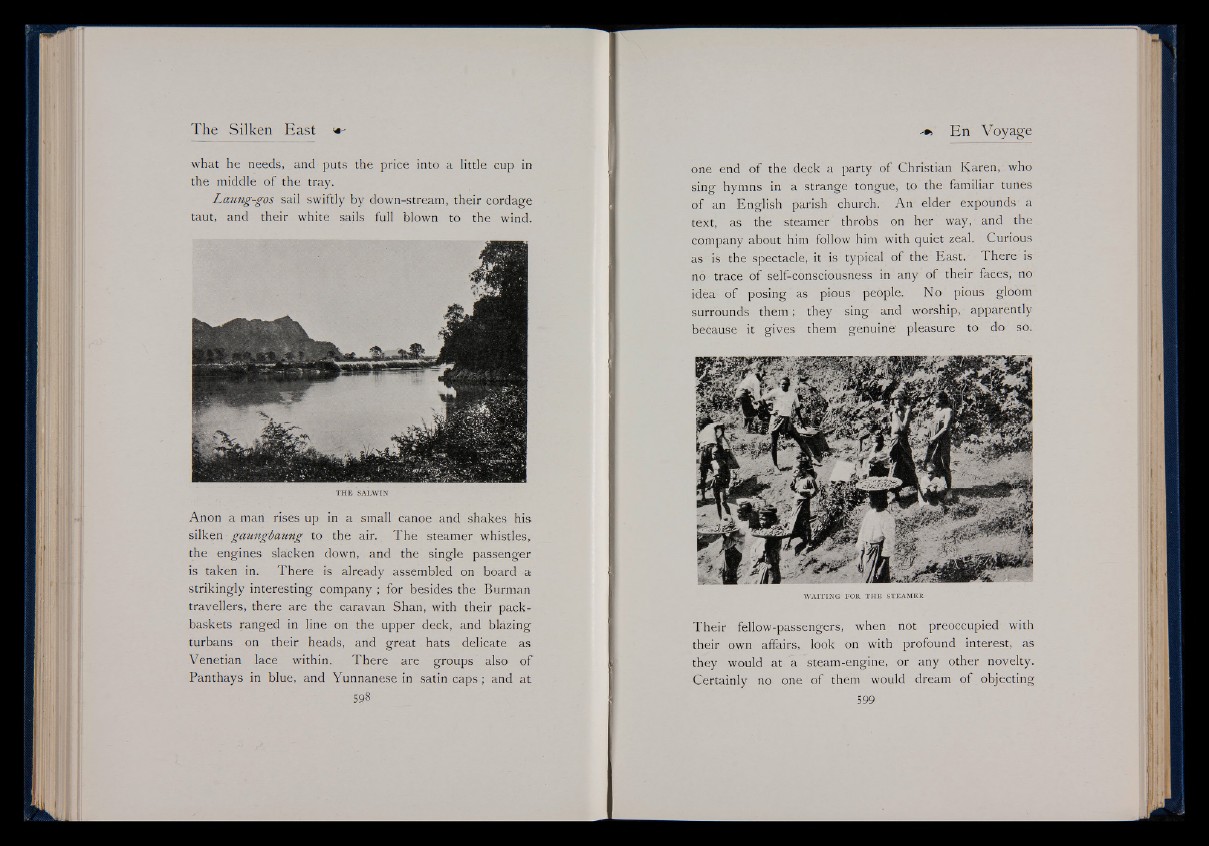

Laung-gos sail swiftly by down-stream, their cordage

taut, and their white sails full blown to the wind.

TH E SALWIN

Anon a man rises up in a small canoe and shakes his

silken gaungbaung to the air. The steamer whistles,

the engines slacken down, and the single passenger

is taken in. There is already assembled on board a

strikingly interesting company ; for besides the Burman

travellers, there are the caravan Shan, with their pack-

baskets ranged in line on the upper deck, and blazing

turbans on their heads, and great hats delicate as

Venetian lace within. There are groups also of

Panthays in blue, and Yunnanese in satin caps; and at

one end of the deck a party of Christian Karen, who

sing hymns in a strange tongue, to the familiar tunes

of an English parish; church. An elder expounds a

text, as the steamer throbs on her way, and the

company about him follow him with quiet zeal. Curious

as is the spectacle, it is typical of the East. There is

no trace of self-consciousness ’ in any of their faces, no

idea of posing as pious people. No pious gloom

surrounds them; they sing and worship, apparently

because it gives them genuine' pleasure to do so.

WAITING FOR TH E STEAMER

Their fellow-passengers, when not preoccupied with

their own affairs, look on with profound interest, as

they would at a. steam-engine, or any other novelty.

Certainly no one of them would dream of objecting