sawpit there came the steady “ swish ” of a steel

saw at work.

1 he hut in which I had passed the night drew,

my closer attention. It was made entirely of bamboo,

save the • thatch, which was of palm-leaves. There

was not a nail in its composition. Its framework was

of round bamboos of graduated size, and its walls and

floor were of hammered bamboo. It was cheap, it

was ephemeral, and it let in the sun and the cold;

but it was new, and clean, and in harmony with its

surroundings. The tent is for the desert Arab ; a

bamboo hut at every resting-place is its happy equivalent

in Burma.

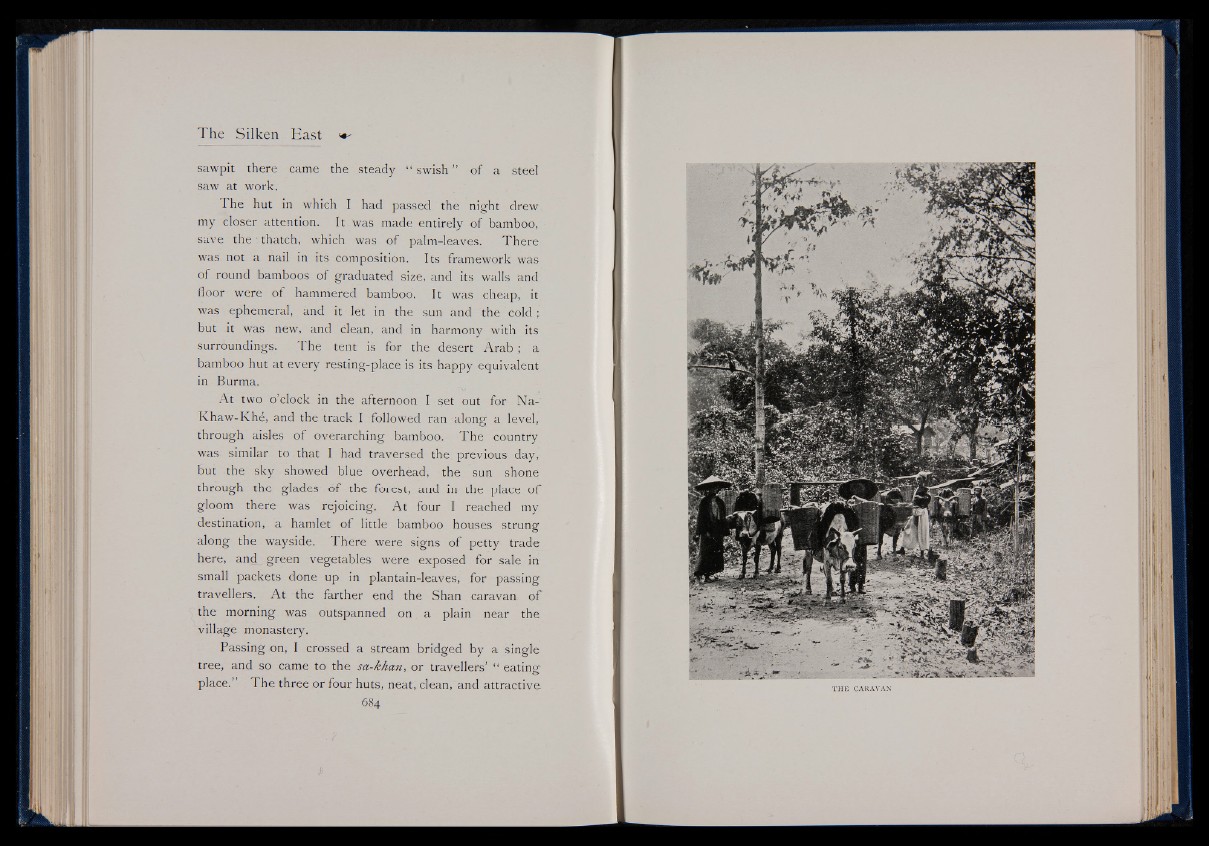

At two o’clock in the afternoon I set out for Na-

Khaw-Khe, and the track I followed ran along a level,

through aisles of overarching bamboo. The country

was similar to that I had traversed the previous day,

but the sky showed blue overhead, the sun shone

through the glades of the forest, and in the place o f

gloom there was rejoicing. At four I reached my

destination, a hamlet of little bamboo houses strung

along the wayside. There were signs of petty trade

here, and green vegetables were exposed for sale in

small packets done up in plantain-leaves, for passing

travellers. At the farther end the Shan caravan o f

the morning was outspanned on a plain near the

village monastery.

Passing on, I crossed a stream bridged by a single

tree, and so came to the sa-khan, or travellers’ “ eatinsr

place.” The three or four huts, neat, clean, and attractive