above the heads o f the players, is the Panthay mosque.

Texts from the Koran in sheets of Arabic letters are

wrapped about its inner pillars, and from its tower the

muezzin daily calls the faithful to prayer. Of the

worshippers many are Chinamen of the obvious type ;

but there are some with the Muslim strain in them,

the strain of the Arab and the Turk. One man, in

a long white robe and red fez, might have come from

toll-collecting at the Golden Horn ; and another, in a

blue gelabieh, would pass unnoticed in the bazaars o f

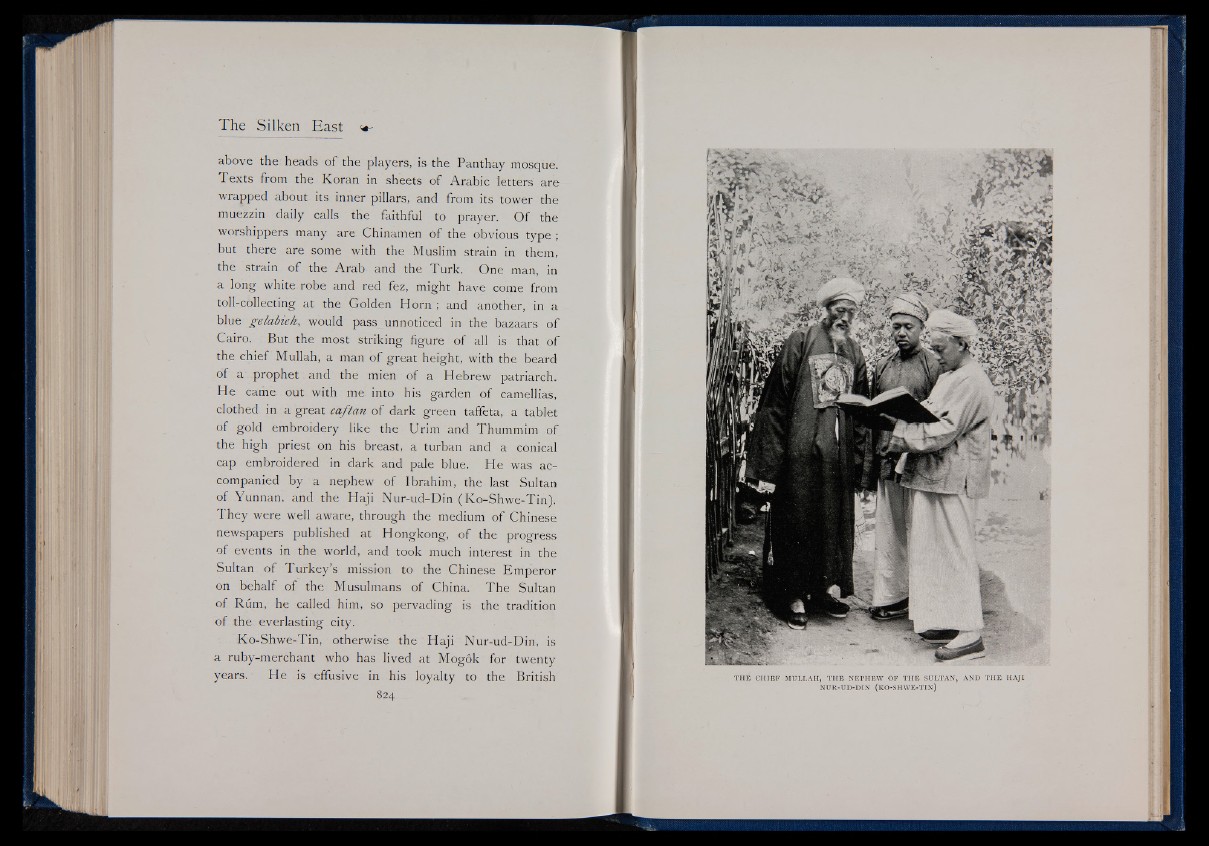

Cairo. But the most striking figure of all is that of

the chief Mullah, a man of great height, with the beard

of a prophet and the mien of a Hebrew patriarch.

He came out with me into his garden of camellias,

clothed in a great caftan of dark green taffeta, a tablet

of gold embroidery like the Urim and Thummim of

the high priest on his breast, a turban and a conical

cap embroidered in dark and pale blue. He was accompanied

by a nephew of Ibrahim, the last Sultan

of Yunnan, and the Haji Nur-ud-Din (Ko-Shwe-Tin).

1 hey were well aware, through the medium o f Chinese

newspapers published at Hongkong, of the progress

of events in the world, and took much interest in the

Sultan of Turkey’s mission to the Chinese Emperor

on behalf of the Musulmans of China. The Sultan

of Rum, he called him, so pervading is the tradition

of the; everlasting city.

Ko-Shwe-Tin, otherwise the Haji Nur-ud-Din, is

a ruby-merchant who has lived at Mogok for twenty

years. He is effusive in his loyalty to the British

824

THE CHIE F MULLAH, TH E NEPHEW OF TH E SULTAN, AND TH E HAJI

NUR-UD-DIN (KO-SHWE-TIN)