some of all the intermediate sizes—marble, stone, wood,

brick, and clay. Some, even of marble, are so timeworn,

though sheltered from change of temperature, that the

face and fingers are obliterated. Here and there are

models of temples, kyoutigs, etc., some not larger than

half a bushel, and some ten or fifteen feet square,

absolutely filled with small idols, heaped promiscuously

one on the other. As we followed the path, which

wound among the groups of figures and models, every

new aspect of the cave presented new multitudes oF

images. A ship of five hundred tons could not carry

away the half of them.”

Here, in fact, are the accumulations of aOg es '; and

the interest of this strange spectacle, to the student o f

Buddhism, lies in the key it offers to the history of the

religion in Burma, of its origins, and the way by which,

it came to the country.

1 he long day of my visit to the caves nears its close,

and in the quiet shelter of the evening I make my way

back to Pha-an. Yet one more sensation remains to

complete the bizarre suggestions of the day. For as

I near the gateways of Pha-gat, I am startled by the

sound of a great flight of birds, a sound as of grey

geese on the wing, but of such volume as can proceed

only from a great host. These are the bats of the

Pha-gat cave. For more than twenty minutes they

sweep out, in a long swift line that grows tortuous as

it recedes; and, as far as I can see into the ruddy-

twilight, the line extends. Swiftly as each creature in it

is flying, it looks in the distance like a smoke spiral

618

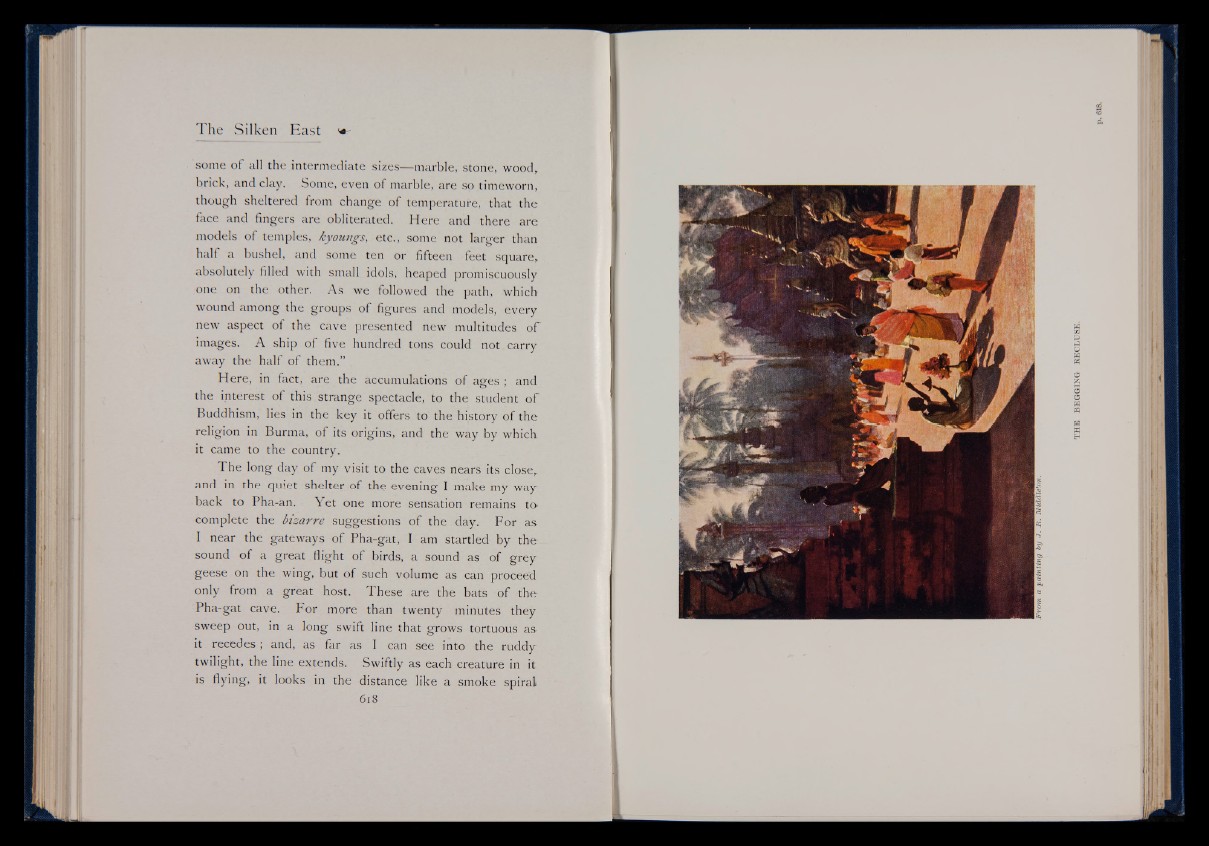

THE BEGGING RECLU