bred by himself, a third was a crafty man at dove-

noosing ; and all were happily free from the squalid

poverty of the nearer East.

Although these men were roughing it, so to speak,

in the jungle, as travellers away from home, they were

possessed of flexible sleeping mats, coloured rugs,

tumblers/- and drinking mugs. They had time for

leisurely meals, and they ceased work at sunset. While

waiting for the rice to boil, they sipped tea from small

Chinese cups, chewed betel, and smoked cheroots.

Good-humour and consideration for each other prevailed

to a remarkable degree amongst them. Each man

seemed to do his share of such work as entailed cooperation

without any pressure. They were all on the

best of terms, and all the evening, though there was

much hilarity, and voices were raised in story-telling

and laughter, there was no note of anger or quarrel.

The Madrasi cook hectored the Karen within his

radius and quarrelled with the Mohammedan peon. The

European censured the dulness of the. guide' who had

misled him the previous day. But bland good-humour

was the atmosphere of the Shan-Burmese encampment.

What a precious quality it is !

I do not suggest that these people are angels without

wings, or even that they are incapable of truculent rage ,

but many years of life and travel in Burma have convinced

me that in the minor self-control which sweetens

human relationships, they far surpass the white man.

I shall not easily forget these pleasant hours in this

little clearing in the jungle. How the slant sun

688

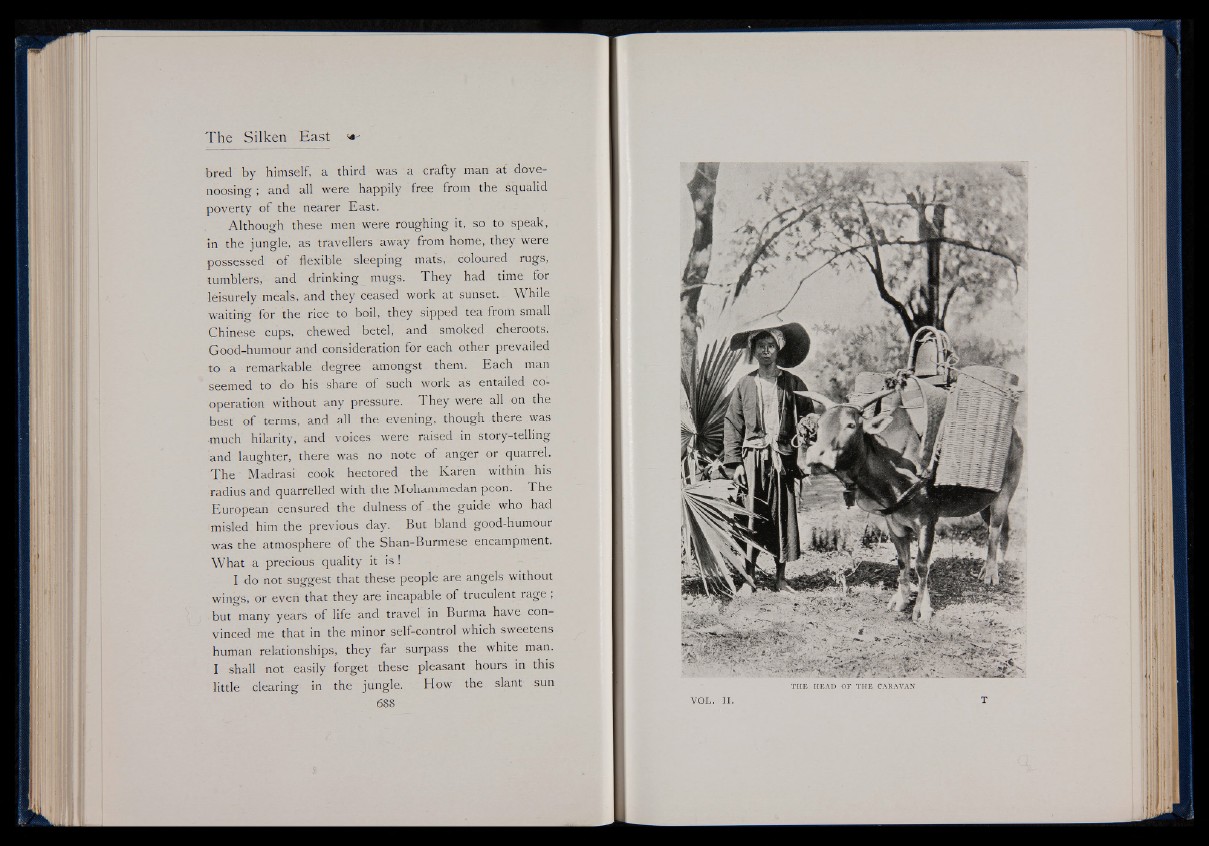

TH E HEAD OF TH E CARAVAN

VOL. II.