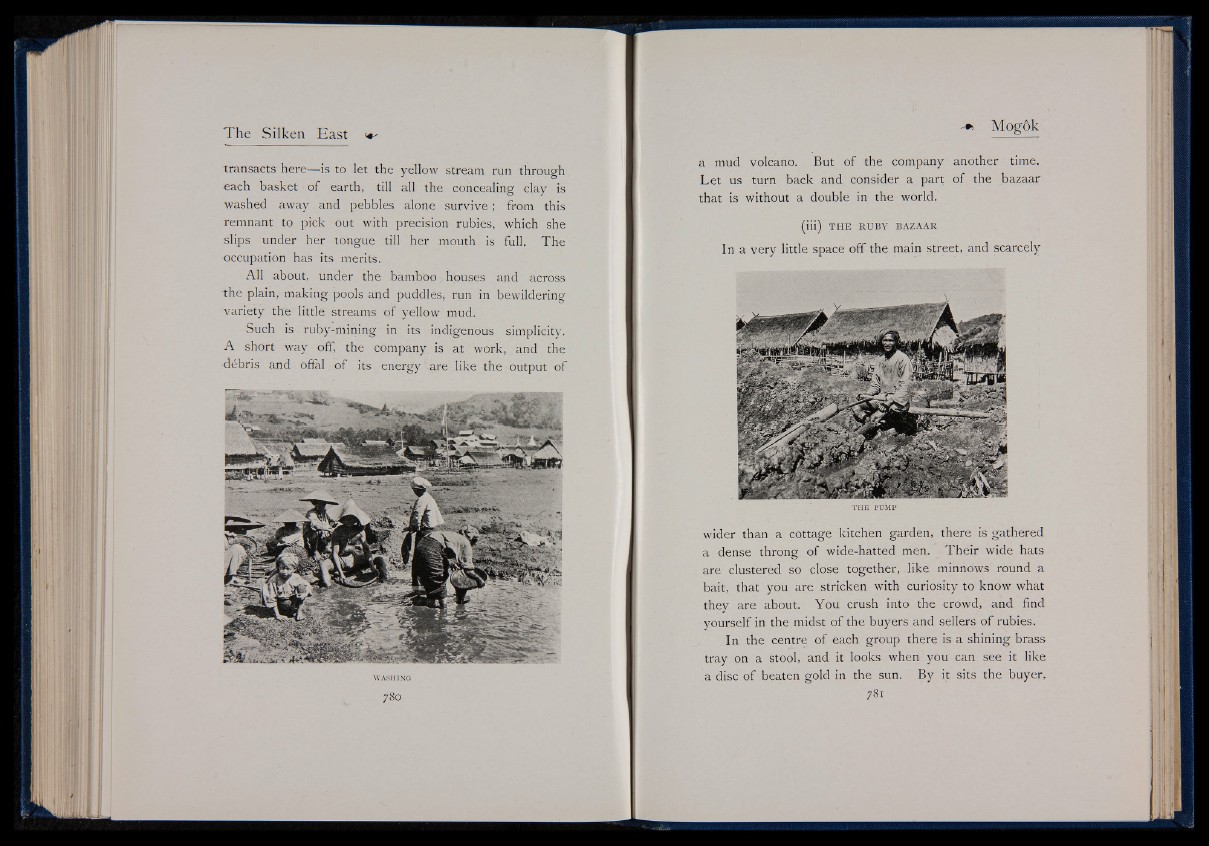

transacts here—is to let the yellow stream run through

each basket of earth, till all the concealing clay is

washed away and pebbles alone survive ; from this

remnant to pick out with precision rubies, which she

slips under her tongue till her mouth is full. The

occupation has its merits.

All about, under the bamboo houses and across

the plain, making pools and puddles, run in bewildering

variety the little streams of yellow mud.

Such is ruby-mining in its indigenous simplicity.

A short way off, the company is at work, and the

débris and offal of its energy are like the output of

WASHING

a mud volcano. But of the company another time.

Let us turn back and consider a part of the bazaar

that is without a double in the world.

( i i i ) TH E RU B Y BAZAAR

In a very little space off the main street, and scarcely

TH E PUMP

wider than a cottage kitchen garden, there is gathered

a dense throng of wide-hatted men. Their wide hats

are clustered so close together, dike minnows round a

bait, that you are stricken with curiosity to know what

they are about. You crush into the crowd, and find

yourself in the midst of the buyers and sellers of rubies.

In the centre of each group there is a shining brass

tray on a stool, and it looks when you can see it like

a disc of beaten gold in the sun. By it sits the buyer,