and its shares that once went a-begging for eighteen-

pence are now unpurchasable for a pound. Let us

consider in more detail some of its methods of

work.

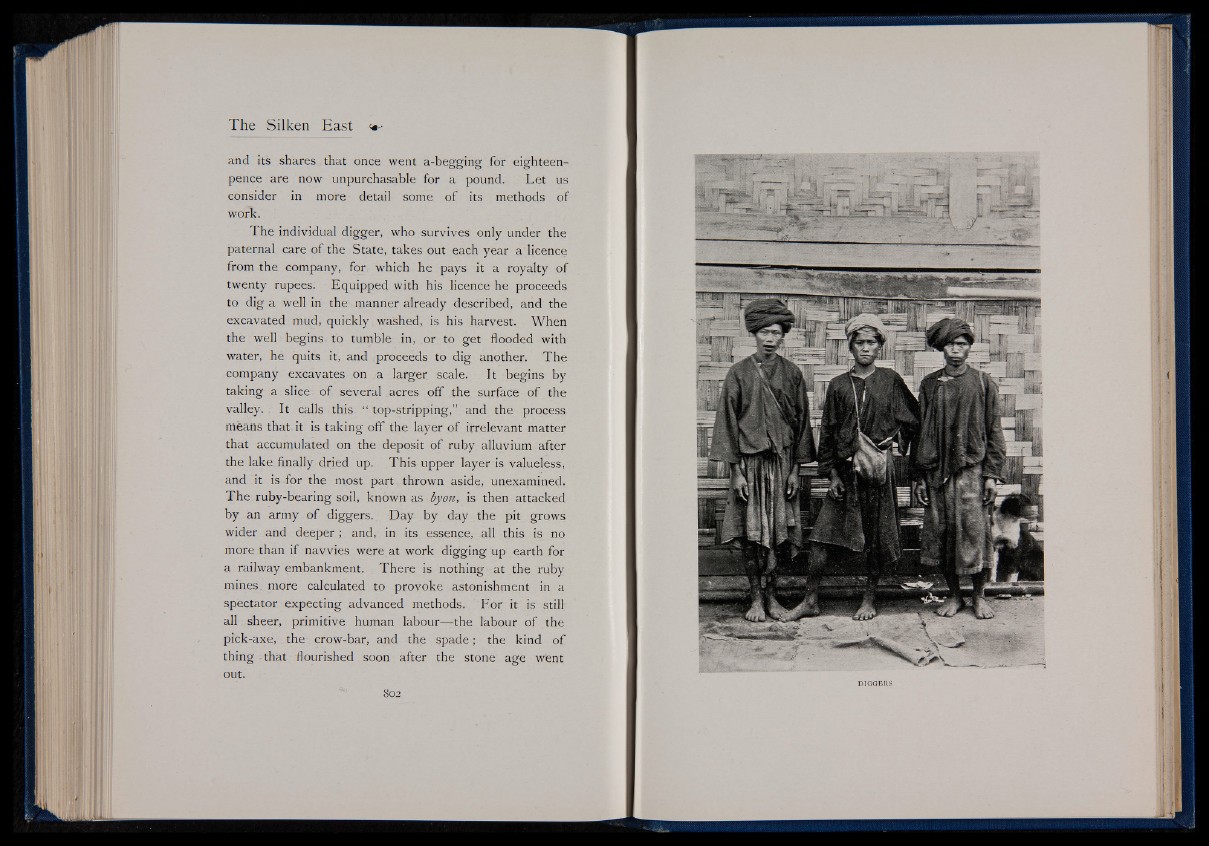

The individual digger, who survives only under the

paternal care of the State, takes out each year a licence

from the company, for which he pays it a royalty of

twenty rupees. Equipped with his licence he proceeds

to dig a well in the manner already described, and the

excavated mud, quickly washed, is his harvest. When

the well begins, to tumble in, or to get flooded with

water, he quits it, and proceeds to dig another. The

company excavates on a larger scale. It begins by

taking a slice of several acres off the surface of the

valley. It calls this “ top-stripping,” and the process

means that it is taking off the layer of irrelevant matter

that accumulated on the deposit of ruby alluvium after

the lake finally dried up. This upper layer is valueless,

and it is for the most part thrown aside, unexamined.

The ruby-bearing soil, known as fyra, is then attacked

by an army of diggers. Day by day the pit grows

wider and deeper ; and, in its essence, all this is no

more than if navvies were at work digging up earth for

a railway embankment. There is nothing at the ruby

mines, more calculated to provoke astonishment in a

spectator expecting advanced methods. For it is still

all sheer,; primitive human labour—the labour of the

pick-axe, the crow-bar, and the spade; the kind of

thing that flourished soon after the stone age went

out.