from Kinchinjhow to Chango-Khang; following a yak-»

track, which led across the Kinhhinjhow glacier, along

the hank of the lake, and thence westward up a very

steep spur, on which was much ice and snow. At

nearly 17,000 feet I passed two small lakes, on the

banks of one of which I found bees, a May-fly and

g n a t; the two latter bred on stones in the water.

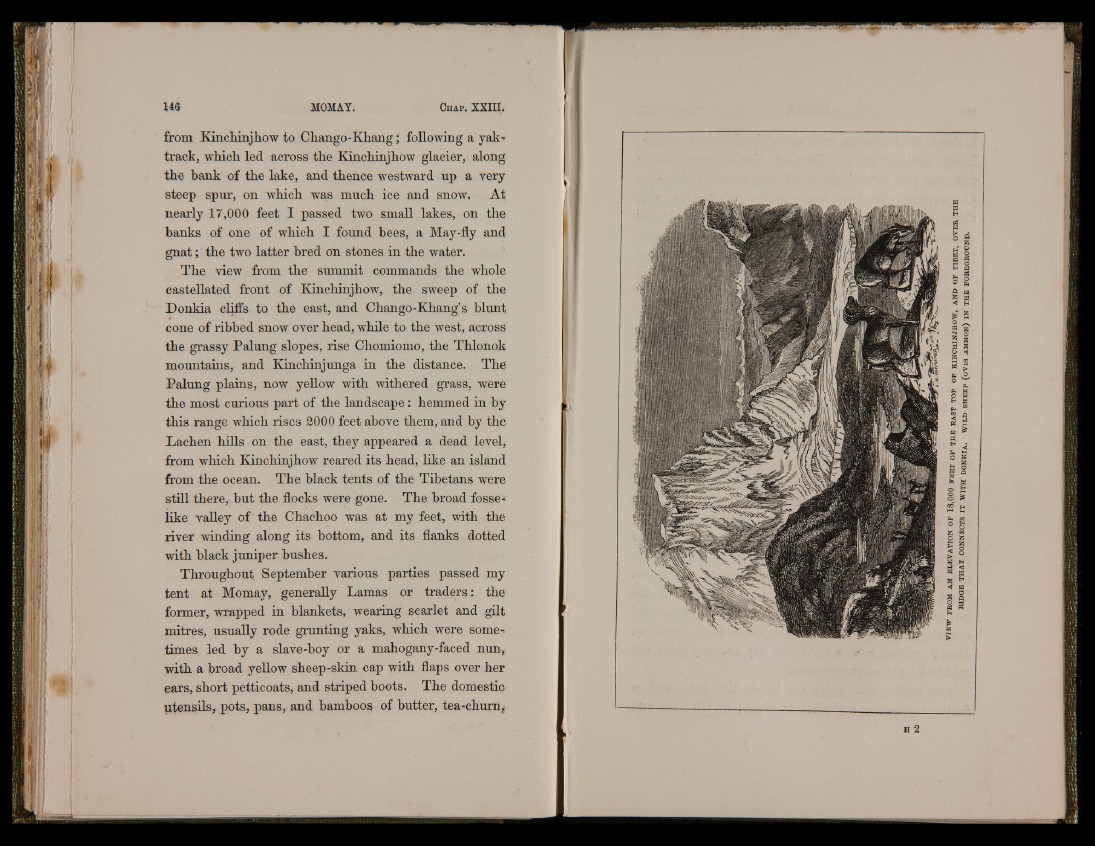

The view from the summit commands the whole

castellated front of Kinchinjhow, the sweep of the

Donkia cliffs to the east, and Chango-Khang’s blunt

cone of ribbed snow over head, while to the west, across

the grassy Palung slopes, rise Chomiomo, the Thlonok

mountains, and Kinchinjunga in the distance. The

Palung plains, now yellow with withered grass, were

the most curious part of the landscape: hemmed in by

this range which rises 2000 feet above them, and by the

Lachen hills on the east, they appeared a dead level,

from which Kinchinjhow reared its head, like an island

from the ocean. The black tents of the Tibetans were

still there, hut the flocks were gone. The broad fosse'

like valley of the Chachoo was at my feet, with the

river winding along its bottom, and its flanks dotted

with black juniper hushes.

Throughout September various parties passed my

tent at Momay, generally Lamas or traders: the

former, wrapped in blankets, wearing scarlet and gilt

mitres, usually rode grunting yaks, which were some'

times, led by a slave-hoy or a mahogany-faced nun,

with a broad yellow sheep-skin cap with flaps over her

ears, short petticoats, and striped hoots. The domestic

utensils, pots, pans, and bamboos of butter, tea-churn,