skin, and the consequences of the great hulk of green

food which it consumes.

The Duabanga is the pride of these forests. Its

trunk, from eight to fifteen feet in girth, is generally

forked from the base, and the long pendulous branches

which clothe the trunk for 100 feet, are thickly leafy,

and terminated hy racemes of immense white flowers,

which, especially when in hud, smell most disagreeably

of assafoetida.

The report of a bed of iron-stone eight or ten miles

west of Punkabaree determined us on visiting the

spot; and the locality being in a dense jungle, the

elephants were sent on a-head.

Lohar-ghur, or “ iron hill,” lies in a thick dry

forest. Its plain-ward flanks are very steep, and

covered with scattered weather-worn masses of ochreous

and black iron-stone, many of which are several yards

long: it fractures with faint metallic lustre, and is

very earthy in p a rts ; it does not affect the compass.

There are no pebbles of iron-stone, nor water-worn

rocks of any kind found with it.

Below Punkabaree the Baisarhatti stream cuts

through banks of gravel overlying the tertiary sandstone.

The latter is gritty and micaceous, intercalated

with beds of indurated shale and clay; in

which I found the shaft (apparently) of a bone. In

the bed of the stream were carbonaceous shales, with

obscure impressions of fossil fern leaves, characteristic

of the Burdwan coal-fields, hut too imperfect to

justify any conclusion as to the relation between

these formations.

Ascending the stream, these shales are seen in situ,

overlain hy the metamorphic clay-slate of the mountains.

This is at the foot of the Punkabaree spur, and close

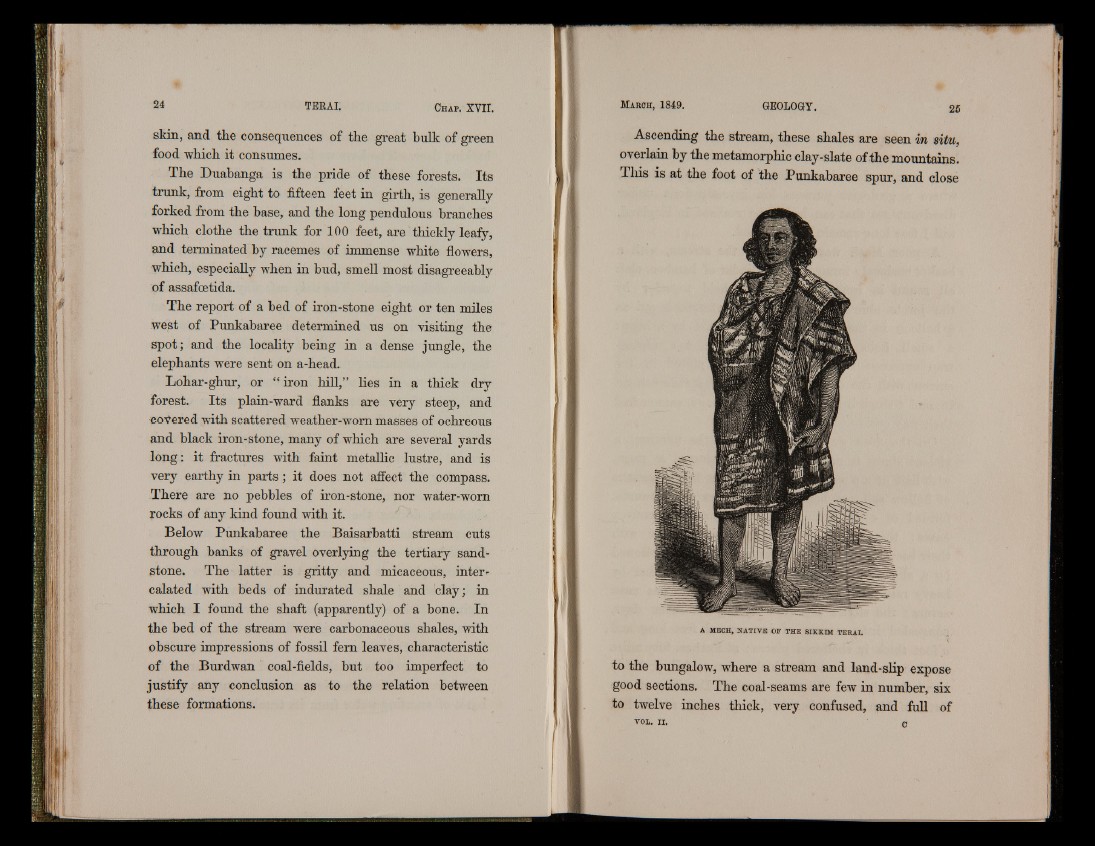

A MECH, NATIVE OF THE SIKKIM TERAI.

to the bungalow, where a stream and land-slip expose

good sections. The coal-seams are few in number, six

to twelve inches thick, very confused, and full of

VOL. I I . e